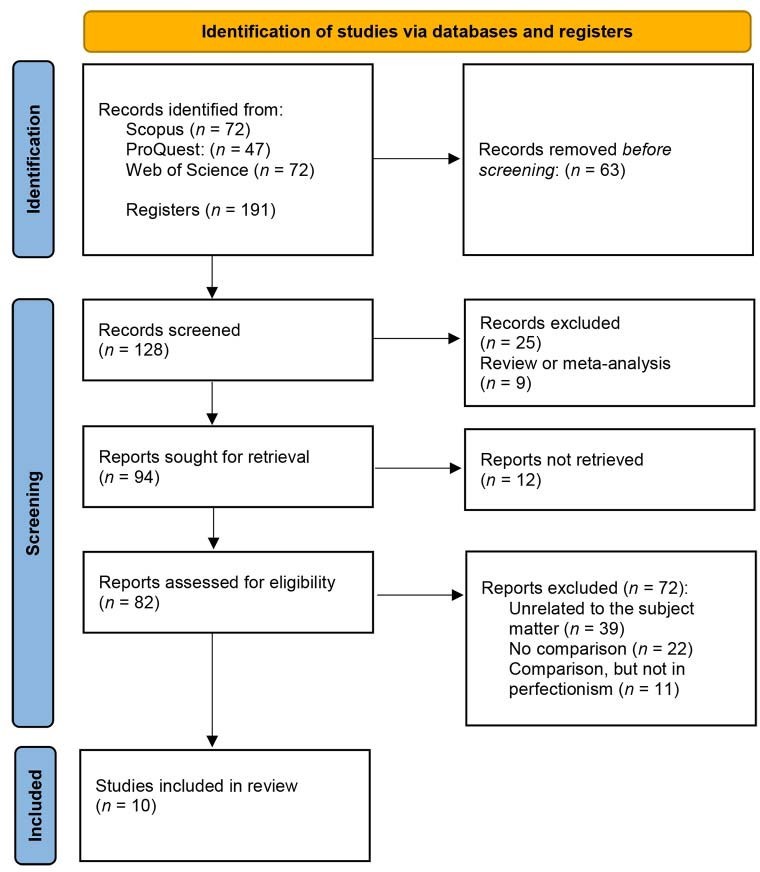

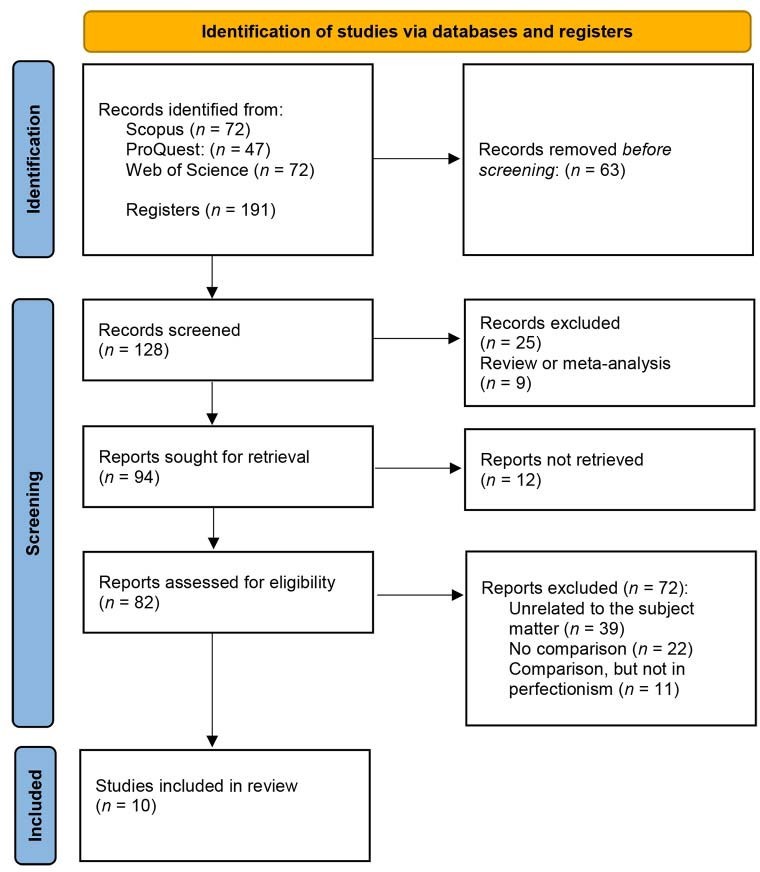

Figure 1

Flowchart of the systematic review article selection process

https://doi.org/10.24265/liberabit.2024.v30n1.806

ARTÍCULO TEÓRICO

Is Perfectionism an Exclusive Characteristics of Gifted Students?

Systematic Review

Revisión sistemática

María Isabel Jiménez Moralesa,*

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7762-5354

Purificación Checa Fernándeza

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8360-1033

aUniversidad de Granada, Andalucía, España

Autor corresponsal

Para citar este artículo:

Jiménez, M. I., & Checa, P. (2024). Is Perfectionism an Exclusive Characteristics of Gifted Students? Systematic Review. Liberabit, 30(1), e806. https://doi.org/10.24265/liberabit.2024.v30n1.806

Abstract

Background: Currently, there is great interest in analyzing perfectionism as a trait especially characteristic of people with high abilities (H.A.A.). However, the findings obtained are heterogeneous and inconclusive, which could be due to the multidimensional nature of this construct, which includes both Negative Perfectionism (NP) and Positive Perfectionism (PP). State of the art: The present systematic review aims to investigate whether perfectionism is a defining and exclusive characteristic of gifted students. According to the criteria of the PRISMA statement, ten publications were included. Conclusions: The results obtained were inconclusive, since in some papers significant differences in perfectionism were found between the AA.CC vs. non-gifted group, while in others no differences were found.

Keywords: Gifted abilities; perfectionism; systematic review; PRISMA.

Resumen

Antecedentes:

actualmente, existe un gran interés por analizar el perfeccionismo como un

rasgo especialmente característico de las personas con altas capacidades (AA.CC).

Sin embargo, la evidencia científica ha aportado

resultados heterogéneos y poco concluyentes, lo que podría deberse a la

naturaleza multidimensional de dicho constructo, que comprende, tanto el

perfeccionismo negativo (PN) como el perfeccionismo positivo (PP). Estado del arte:

la presente revisión

sistemática pretende profundizar

si el perfeccionismo es una característica definitoria y exclusiva del

estudiantado superdotado. Conclusiones:

según los criterios de la declaración PRISMA,

solo diez publicaciones cumplieron los criterios de inclusión. Los resultados

obtenidos fueron poco concluyentes, ya que en algunos trabajos se encontraron

diferencias significativas en perfeccionismo entre el grupo de AA.CC. vs. no superdotados,

mientras que en otros no se

encontraron diferencias.

Palabras clave:

altas capacidades; perfeccionismo; revisión sistemática; PRISMA.

The study of intelligence has been one of the areas that has aroused most interest over the centuries and, for several decades, one of the most investigated psychological constructs, due to its important role in learning. A review of the literature shows that there are as many perspectives and theoretical approaches to intelligence as there are authors, as well as reflections on the theoretical structure of, for example, Sternberg’s triarchic model of intelligence (Damasceno et al., 2022) or Gardner´s Multiple Intelligences Theory (Cavas & Cavas, 2020), oriented to overcome the difficulty implied by the absence of a consensual definition (Leana-Tascilar & Kanli, 2014). On the one hand, there are researchers who understand intelligence as the ability to learn and apply acquired knowledge, in order to reorganize their behavioral patterns, which allows for better adjustment and adaptation of the individual to their environment (Marina, 1993, seen in Molero et al., 1998; Simonton, 2003; Sternberg, 2012), while others conceive it as the ability to solve problems, using assimilated information (Anderson, 2005; Gardner, 1993; Mayer, 1983).

The same is true when we try to define giftedness or high ability. Throughout our lives, we encounter individuals with an astonishing learning speed, high commitment and impeccable performance, who, without apparent effort, make original contributions (Subotnik et al., 2011). Although, under the denomination of giftedness, we can find very different profiles, these are some of the most representative characteristics of the people who make up this heterogeneous group. For some authors, giftedness is the combination of the expression of potential and performance at the upper end of the talent continuum. These individuals show outstanding levels of aptitude (extraordinary capacity forreasoning and learning) or competence (understood as performance in the top 10% or rarer) in one or more domains, such as a symbol system (mathematics, music or language), or a set of sensorimotor skills (painting, dance or sports) (Stricker et al., 2019).

The National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC) argues that gifted students outperform their peers of the same age, experience and environment in one or more areas (National Association for Gifted Children, 2019). Likewise, in order for them to have the same learning opportunities as their non-gifted peers, it is vital that they are identified early and that their specific educational support needs are met, thus favoring their identification and appropriate development and the expression and realization of their potential in all family socioeconomic status or types of educational institution (Navarro-Saldaña et al., 2022).

The three-ring model, advocated by Renzulli (1994), is one of the most widely accepted in the scientific community for its approach to giftedness based on three defining traits: above-average intellectual ability, high motivation and perseverance (Barriopedro et al., 2018) and high level of creativity. In turn, it is interesting to note that intellectual giftedness, in addition to referring to high cognitive performance, implies greater complexity at the emotional level (Gillioz et al., 2023), specifically: greater moral judgment, self-awareness and sensitivity to the expectations and feelings of the people around them (Patti et al., 2011) and other as Prieto et al. (2017). This greater emotional intensity is interpreted by some authors as a risk factor (Janos & Robinson 1985; Roedell 1986) that generates more stress, greater social maladjustment and preoccupation with interpersonal conflicts.

On the other hand, other authors argue that this greater emotional complexity is a protective element that facilitates positive coping with stress and conflict and greater intrapersonal and interpersonal understanding (Beer, 1991; Freeman, 1983, 1994). There is also another trait attributed to gifted students: perfectionism. This construct is associated with a cognitive control style and high standards of performance and preoccupation with making mistakes (Sastre-Riba et al., 2019). Initially, it was considered unidimensional (Burns, 1980, seen in Fletcher & Speirs, 2012), but thanks to the pioneering work of Hamachek (1978) and other authors, such as Frost et al. (1990), it began to be considered multidimensional.

In this paper, we focus on the two main dimensions: perfectionistic concerns, understood as negative perfectionism, and perfectionistic strivings, understood as positive perfectionism. On the one hand, there are perfectionist concerns, which include worries about failure, doubts about personal abilities and behaviors performed, a sense that the environment demands perfection, and the impression that there is inconsistency between the standards set and the performance that takes place (Dunkley et al., 2003; Schuler, 2000). In this line, recent meta-analysis study by Ferber et al. (2024) examined the relationships between dimensions of perfectionism and social anxiety and their findings showed large to very-large-sized associations between social anxiety and dimensions of perfectionism related to perfectionistic concerns, namely socially prescribed perfectionism, doubts about actions, concerns over mistakes, and discrepancy, as well as self- presentational perfectionism.

The Perfectionist Social Disconnection Model brings a theoretical framework suggesting an explanation of the associations between maladaptive perfectionism and mental health problems such as depression, eating disorders, hazardous drinking, and anxiety (Hewitt et al., 2018). According to this model, maladaptive perfectionists experience subjective and objective social disconnection throughout their own relational styles that involve interpersonal hostility and sensitivity. In turn, the social disconnection leads to increased levels of psychological vulnerability (Chemisquy, 2017).

In gifted students, these have been related to indicators of psychological maladjustment in academic contexts (e.g., procrastination or academic ineffectiveness) and non-academic contexts (e.g., life satisfaction or intrinsic motivation, which, in turn, leads to underachievement and anxiety) (Fletcher & Speirs, 2012; Frost et al., 1993; Stoeber & Rambow, 2007).

On the other hand, there are perfectionistic strivings, which are related to setting high goals and the conviction that it is fundamental to one’s personal worth to achieve them. Thanks to them, individuals take pleasure in striving for excellence while acknowledging their limitations (Ogurlu, 2020; Schuler, 2000). Thus, this perfectionist drive may be psychologically and educationally desirable for exceptionally gifted students and have a positive impact on their grades, perceived self-efficacy and social relationships (Andrews et al., 2014; Stoeber & Rambow, 2007; Stricker et al., 2019; Terry-Short et al., 1995; Wang et al., 2012). Despite this, and as Mofield and Parker (2018) argue, the question of whether perfectionism is a trait that gifted people show to a greater extent is currently a controversial issue among experts, due to the relationship it has with high performance and excellence, although this is not always manifested in people with exceptional ability (Sastre-Riba & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2019).

For them, some consider that there is a strong relationship between perfectionism and giftedness, which would explain the psychological adjustment difficulties that some of these students present (Silverman 1997; Speirs, 2007; Speirs & Finch 2006), while for others, there is insufficient empirical evidence (Parker & Mills 1996; Parker et al. 2001).

The relevance of perfectionism in an educational context is clear, due to its effect on achievement, both in gifted and non-gifted students. Madigan (2019) who meta-analysed the findings of 37 studies (N = 8901) that examined perfectionism and academic performance, found that Perfectionistic Straivings (PS) showed a significant positive relationship with academic performance, whereas Perfectionistic concern (PC) showed a significant negative relationship with academic performance.

Perfectionism has long been recognised as a psychological factor that may influence the healthy adjustment of young academically gifted students. To examine the role of perfectionism among these students Grugan et al., (2021), conducted a systematic review examining perfectionism in young student.

Thus, the aim of the present review was to find out whether or not perfectionism is a defining characteristic unique to gifted students.

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy. This review was carried out following the guidelines set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), with the aim of making it systematic and transparent. A standardized literature search was conducted on August 7th 2023 in Scopus, Web of Science and ProQuest, which are reputable and reliable databases for systematic reviews. The search equations used to narrow down the information was «gifted AND perfectionism» and «gifted OR perfectionism», although only for the title, abstract and keywords. Subsequently, both databases were joined by the AND connector. All articles selected belong to scientific journals and have been published in the last 11 years, i.e., from 2012 to 2023.

2.2. Eligibility criteria. The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) empirical studies, (2) published in a scientific journal with full-text access and written in English/Spanish, (3) conducted on students in either schools (primary education) or high schools (secondary education), (4) where perfectionism is analyzed, and (5) where there is a comparison between gifted and non-gifted students.

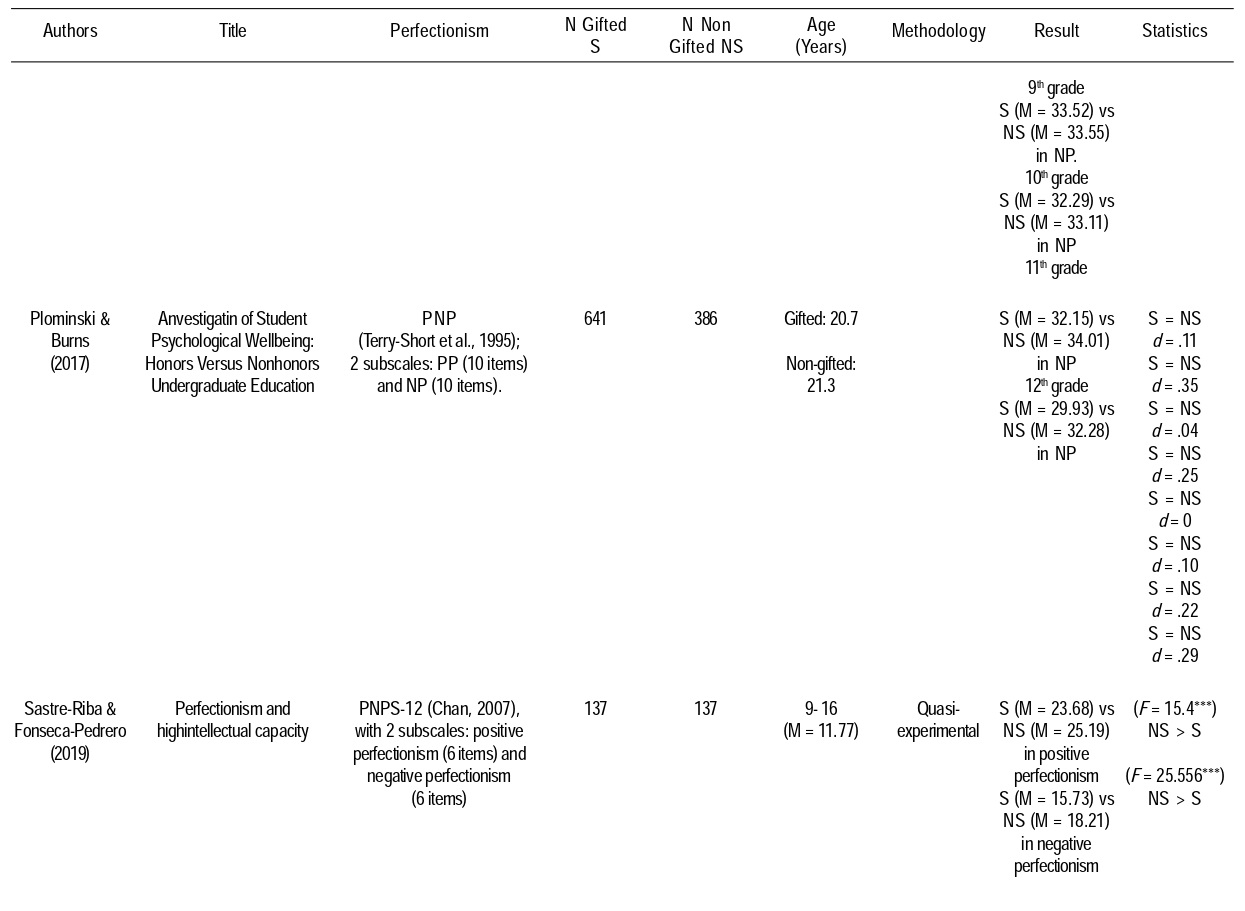

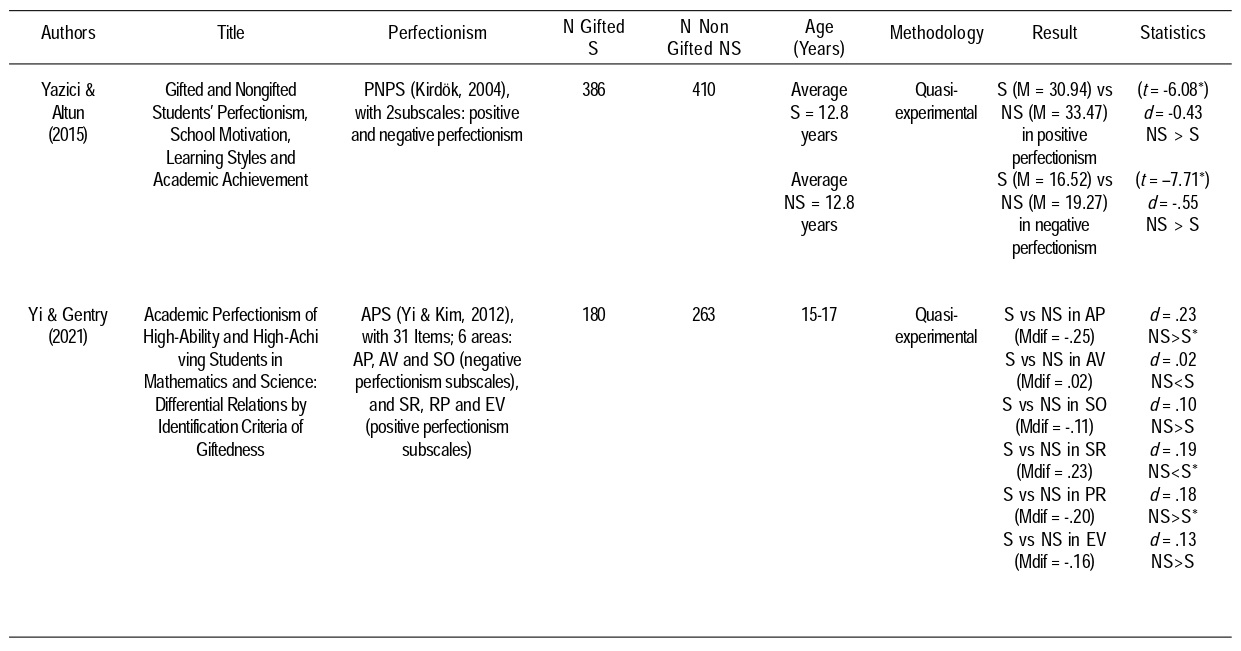

2.3. Article search and selection process. Following this search, a total of 191 documents were registered and, after eliminating those that were duplicated (63), 128 remained to be reviewed. To continue with the process, the eligibility criteria were considered via title review, discarding 25 articles, as they were not related to the selected subject matter, and another 9 articles, which were either reviews or meta-analyses. Of the remaining 94 records, others were discarded, following the same procedure mentioned above but, on this occasion, by reading the abstract: 39 for not being related to the chosen subject, 22 for not comparing students with and without intellectual endowment, and 11 in which there was no comparison in perfectionism. This produced a total of 10 publications, which were analyzed for the systematic review (See Figure 1).

2.4. Coding of results. In order to

carry out a proper analysis of the articles, various data were extracted from

them: the names of the authors and their corresponding work, the instruments used to measure

the dependent variable (perfectionism)

and its levels (the scales and their sub-dimensions), the characteristics of

the sample (number of participants, distribution by sex, age, place of origin),

the methodology in which the research is ascribed, and the main results of the

study.

Figure 1

Flowchart of the systematic review article selection process

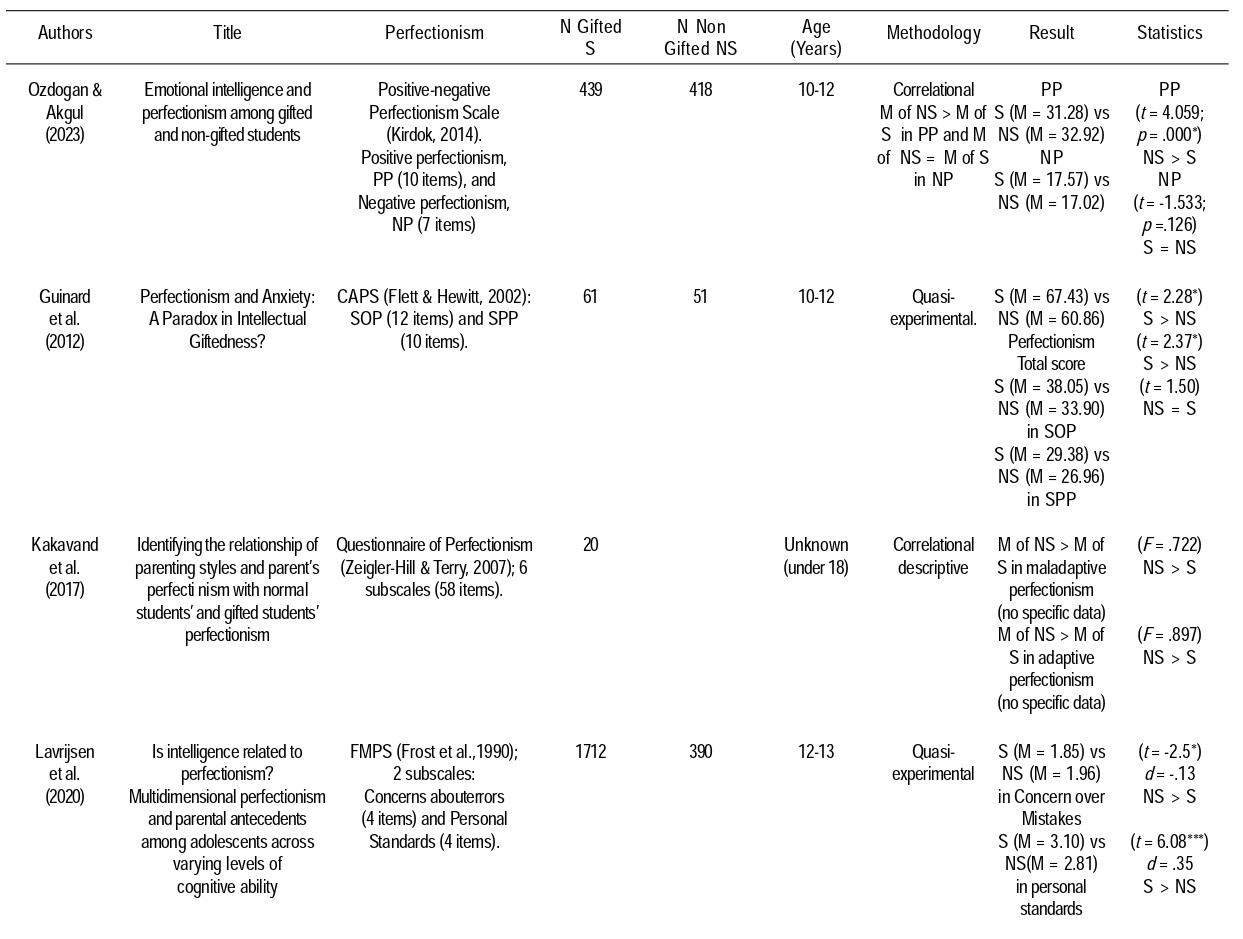

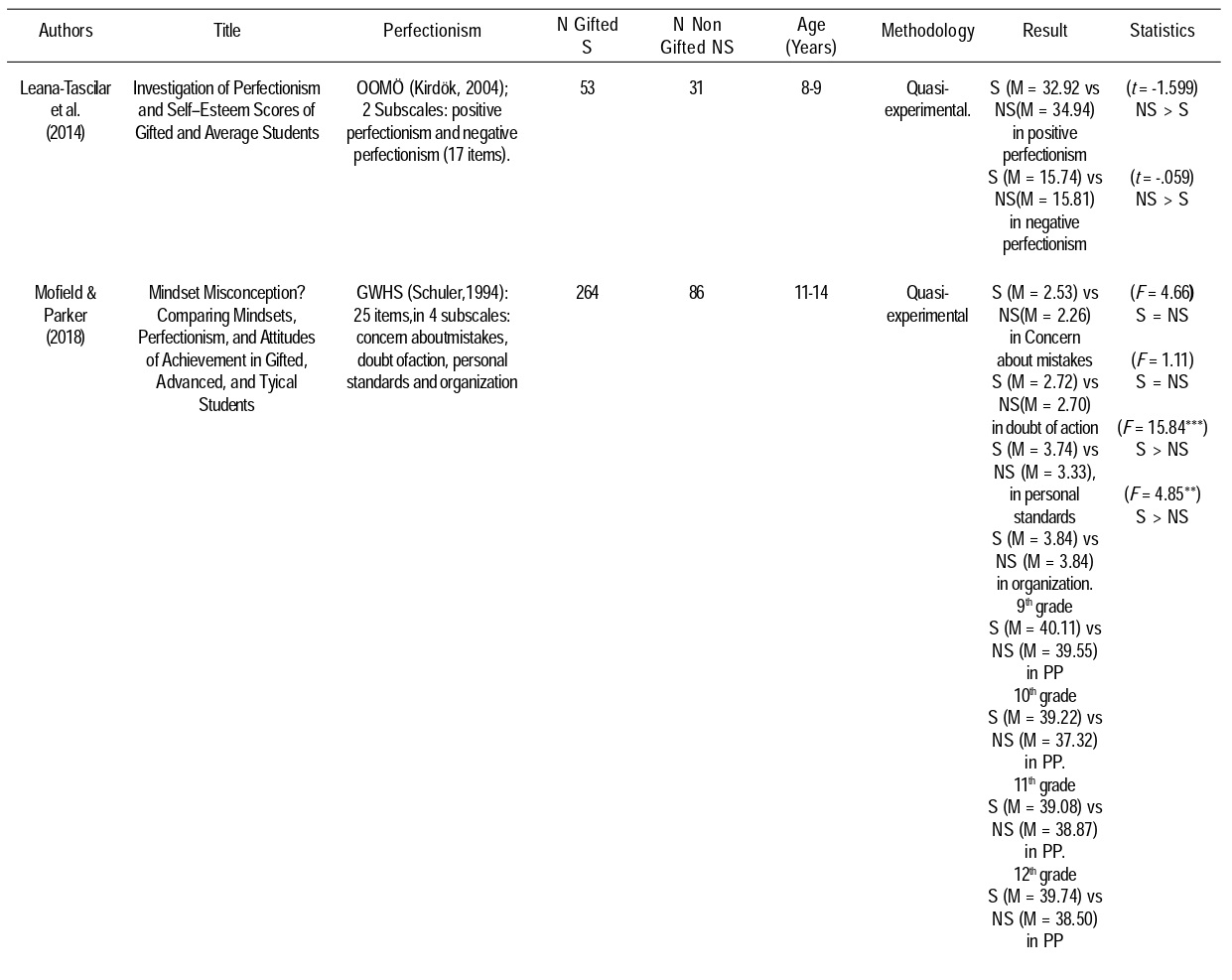

Main characteristics of the studies selected for the review

The analysis of the results produced contradictory data. On the one hand, some studies show a relationship between positive perfectionism and giftedness in age groups between 11 and 17 years. In some studies, the mean positive perfectionism scores of highly gifted students are higher than those of the non-gifted group, with Student’s t-values ranging from 2.28 to 6.08, or F-values ranging from 4.85 to 15.84, and p-values ranging from .001 to .05. In contrast, there are other studies in which the age range is 12 to 16 years, the t-value is around -6.08, or F is around 15.4, and the p-values are between p < .05 and p < .001, indicating that it is the group of typical students who obtain higher mean scores in positive perfectionism than the group of people with high intellectual endowment. Lastly, other articles, with a lower mean age, t (-1.599) or F (.722), drew the same conclusions regarding the difference between the groups, although with a different significance (p > .05).

Likewise, and in relation to negative perfectionism, articles have been found which conclude that the group with normative intelligence obtains higher mean scores in this dimension of perfectionism. In all of them, the same agreement is reached, but they differ in the importance that can be given to the result: in those where this ranges from p < .001 to p < .05, the age of the students is between 12 and 17 years, t ranges from -7.71 to 6.08 and F is above 25. However, when p > .05, the mean age is lower and so are the values of t (-.059) and F (.897).

Finally, there are several results that deviate from the line that had been advocated by the previously mentioned studies. The age range of these studies is similar to that of the previous studies (from 11 to 21 years) and the t-values (1.50) and F (4.66) are also similar, although the point is that there are no differences in the mean scores between the groups in any of the dimensions of perfectionism we are interested in. In addition, few articles provide the effect size of their research, showing a small effect size (d < .5).

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted. It is often assumed that perfectionism is an exclusive characteristic of highly gifted individuals (Stricker et al., 2019). However, although there is a large literature on this relationship, the results obtained in studies are ambiguous and inconsistent (Ogurlu, 2020), hence the importance of this work. From the review that we carried out to respond to the objective set out at the beginning of this study, we discovered that there are authors who support this hypothesis, reporting the existence of higher perfectionism scores in the profiles of gifted students, especially in the positive dimension of perfectionism (Guignard et al., 2012; Lavrijsen et al., 2020; Mofield & Parker, 2018; Yi & Gentry, 2021). This could be explained by the ambition that characterises these students and their motivation to tackle complex challenges (Guignard et al., 2012). As a result of this deliberate pursuit, they are more likely to maintain high levels of well-being and to develop optimally (Lavrijsen et al., 2020). Following the same reasoning, this could be due to the absence of concern for maintaining the identity of being smart, focusing more on achieving self-determined goals (Mofield & Parker, 2018). Therefore, it would be a positive striving for excellence. In the same way, this perfectionism of positive efforts that characterises them would be free of negative self-criticism, thus becoming a greater incentive for the achievement of goals (Yi & Gentry, 2021). Likewise, other studies have found the opposite results, i.e., non- gifted individuals obtain higher scores in positive perfectionism (Kakavand et al., 2017; Leana-Tascilar & Kanli, 2014; Ozdogan & Akgul 2023; Sastre-Riba & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2019; Yazici & Altun, 2015; Yi & Gentry, 2021). A possible explanation for these findings could be the school demotivation that highly gifted students usually suffer in academic contexts, which are designed for typical students. Therefore, the difficulties of schools in adapting school curricula to the interests and needs of these students and exposing them to repetitive tasks, which do not challenge them, might diminish their interest in striving and trying to achieve their best (Yazici & Altun, 2015; Yi & Gentry, 2021).

Regarding the other dimension of perfectionism, i.e., its negative side, there is also considerable confusion regarding the opinions provided by different researchers. Contrary to popular belief, there is no evidence that gifted students have more negative perfectionist tendencies than others (Kakavand et al., 2017; Leana-Tascilar & Kanli, 2014). Moreover, it has been argued that the will to achieve academic superiority in gifted individuals is a power that favours success, rather than negative perfectionism, which is related to failure and personal problems (Leana-Tascilar & Kanli, 2014).

In general, it has been observed that scores on this dimension tend to be higher in normative students (Kakavand et al., 2017; Leana-Tascilar & Kanli, 2014). However, other studies have found a difference in favour of the average student, although such difference is not relevant (Lavrijsen et al., 2020; Sastre-Riba & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2019; Yazici & Altun, 2015; Yi & Gentry 2021). Furthermore, some researchers have reported no differences in mean scores between gifted and non-gifted groups in any of the dimensions of perfectionism (Plominski & Burns, 2017).

Based on all the above information, it can be observed that there is no homogeneity in the opinions on the connection between perfectionism and giftedness, thus the search for perfection cannot be attributed to a specific group of people. Throughout the present systematic review, several issues emerged that limit the scope of the findings. Firstly, the review is based on information gathered from a total of 9 articles, due to the paucity of literature published in the last decade, thus any conclusions drawn would be weak.

Secondly, there are methodological limitations: the samples used in most of the studies are small, and they are focused exclusively on the primary and secondary school population. In order to extend it to other age ranges, further research should delve into perfectionism at the undergraduate level, since there is little literature on the subject and it is a unique developmental stage (Broido & Schreiber 2016).

Thirdly, the selected studies do not distinguish between students on the basis of gender. Research shows that gifted boys have higher levels of perfectionism than girls of the same gender and age, and this could be related to expectations of men in patriarchal societies (Leana-Tascilar & Kanli, 2014). Thus it would be a good idea for future projects to further investigate this aspect.

In addition, other limitations of the systematic review were related to language, databases used and period of inclusion. It has been noted that very few publications include the effect size of their experiments, and, in those where it is provided, its magnitude is small. Therefore, the difference in the perfectionist drive between intellectually gifted and typical students should be interpreted with great caution.

On another level, it would be interesting to investigate the origin of this perfectionism. The aim would be to develop a series of measures to prevent the negative side, associated with dissatisfaction or even depression, which can critically affect their mental health, or at least to reduce the impact it has on people. The factors that cause it could include the demands of parents and their parenting style, which would affect gifted and non-gifted adolescents alike (Mudrak, 2011). Another factor is that perfectionism is conceived as a stereotype associated with giftedness, generating anxiety due to the effort to conform to it and thus gain acceptance from the environment (Gross, 1998). Results pointed to parental and societal expectations as the main aspects involved in the development of perfectionism, which sheds light on how to support the manifestation of perfectionism both in educational and clinical realms (González et al., 2017). In conclusion, this systematic review shows that there is no empirically-based agreement on the assumption that there is a higher prevalence of perfectionism in gifted individuals, or that it is a central characteristic of gifted students, or even that perfectionistic concerns or efforts are more prevalent in the gifted group or the non-gifted group. Although being a perfectionist is not a negative characteristic and is even recommended in some situations, it is necessary to avoid the perfectionism that is related to stress, procrastination and underachievement, as it can have harmful repercussions on achievement, self-esteem and even emotional well-being. For this reason, future research should examine the combined (or interactive) effects of the two dimensions in the same person to advance the understanding of how combinations of high perfectionistic strivings and high perfectionistic concerns affect students’ performance. All this justifies the need for further research.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Throughout the study process, ethical principles and the safeguarding of the participants’ well-being were taken into account. We respected the voluntary and anonymous participation of the insured, who were given a letter of informed consent in which we indicated the commitment to avoid individual identification. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Regional Development Coordination of the Center for Research in Food and Development (CIAD).

PCF: Writing and revising the manuscript

MIJM: Writing and revising the manuscript

Anderson, M. (2005). Intelligence. In Z. Wildsmith (ed.), Microsoft Encarta Premium Suite (vol. 2005). Microsoft Corporation.

Andrews, D. M., Burns, L. R., & Dueling, J. K. (2014). Positive Perfectionism: Seeking the Healthy «Should», or Should We? Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2(8), 27-34. http://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2014.28005

Beer, J. (1991).

Depression, General Anxiety, Test Anxiety, and Rigidity of Gifted Junior High and

High School Children. Psychological Reports, 69(3),

1128-1130. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1991.69.3f.1128

Barriopedro, M. I., Quintana, I., & Ruiz, L. M. (2018). La perseverancia y pasión en la consecución de objetivos:

Validación española de la Escala Grit de Duckworth. RICYDE. Revista Internacional de Ciencias

del Deporte, 54(14), 297-308. https://doi.org/10.5232/ricyde2018.05401

Broido, E. M., & Schreiber, B. (2016). Promoting Student Learning and Development. New Directions for Higher Education, 2016(175), 65-74. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20200

Çavas, B., & Çavas, P. (2020). Multiple Intelligences Theory–Howard Gardner. In B. Akpan, & T. Kennedy (eds.), Science Education in Theory and Practice, An Introductory Guide to Learning Theory (pp. 405-418). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43620-9_27

Chan, D. W. (2007). Positive and Negative Perfectionism among Chinese Gifted Students in Hong Kong: Their Relationships to General Self-Efficacy and Subjective Well-Being. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 31(1), 77-102. https://doi.org/10.4219/jeg-2007-512

Chemisquy, S. (2017).

Las dificultades interpersonales de los perfeccionistas: consideraciones teóricas sobre el modelo

de desconexión social. Revista Argentina De Ciencias Del

Comportamiento, 9(2), 77-92.

Damasceno, R. O., Nascimento, A. M., & Roazzi, A. (2022). Reflexões teóricas, metodológicas e práticas do modelo triárquico da inteligencia de Sternberg. Revista AMAzônica.

Revista de Psicopedagogia, Psicologia

escolar e Educação, 15 (2), 151-188.

Dunkley, D. M., Zuroff, D. C., & Blankstein, K. R. (2003). Self-Critical Perfectionism and Daily Affect: Dispositional and Situational Influences on Stress and Coping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(1), 234-252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.234

Ferber, K., Chen, J., Tan, N., Sahib, A., Hannaford, T., & Zhang, B. (2024). Perfectionism and Social Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. [advance online publication]. https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000201

Fletcher, K. L., & Speirs, K. L. (2012). Research on Perfectionism and Achievement Motivation: Implications for Gifted Students. Psychology in the Schools, 49(7), 668-677. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21623

Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2002). Perfectionism and Maladjustment: An Overview of Theoretical, Definitional, and Treatment Issues. In G. L. Flett, & P. L. Hewitt (eds.), Perfectionism: Theory, Research and Treatment (pp. 5-31). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10458-001

Freeman, J. (1983). Emotional Problems of the Gifted Child. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24, (3), 481-485. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1983.tb00123.x

Freeman, J. (1994). Some Emotional Aspects of Being Gifted. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 17(2), 180-197. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235329401700207

Frost, R. O., Heimberg, R. G., Holt, C. S., Mattia, J. I., & Neubauer, A. L. (1993). A Comparison of Two Measures of Perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 14(1), 119-126. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(93)90181-2

Frost,

R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The Dimensions of Perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14(5), 449-468.

https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01172967

Gardner, H. E. (1993).

Multiple intelligences: The theory in practice. Basic

Books/Hachette Book Group.

Gardner, H. E. (2011). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple

Intelligences. Basic Books.

Gillioz, C., Nicolet-dit-Félix, M., & Fiori, M. (2023). Emotional Intelligence and Emotional Hypersensitivity in Gifted Individuals. Journal of

Intelligence, 11(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11020020

González, A., Gómez-Arízaga, M. P., & Conejeros-Solar, M. L. (2017). Caracterización del

perfeccionismo en estudiantes con alta capacidad: un estudio de casos

exploratorio. Revista De Psicología, 35(2), 581-616. https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.201702.008

Gross, M. U. (1998). The «Me» Behind the Mask: Intellectually Gifted Students and the Search for Identity. Roeper Review, 20(3), 167-174. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783199809553885

Grugan, M., Hill, A., Madigan, D., Donachie, T., Olsson, L., & Etherson, M. (2021). Perfectionism in Academically Gifted Students: A Systematic Review. Educational Psychology Review, 33, 1631-1673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09597-7

Guignard, J. H., Jacquet, A. Y., & Lubart, T. I. (2012). Perfectionism and Anxiety: A Paradox in Intellectual Giftedness? PLoS ONE, 7(7), e41043. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0041043

Hamachek, D. E. (1978). Psychodynamics of Normal and Neurotic Perfectionism. Psychology: A Journal of Human Behavior, 15(1), 27-33.

Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., Mikail, S. F., Kealy, D., & Zhang, L. C. (2018). Perfectionism in the Therapeutic Context: The Perfectionism Social Disconnection

Model. In J. Stoeber (ed.), The psychology

of perfectionism: Theory,

research, applications (pp. 306-329). Routledge. https://www.proquest.com/books/perfectionism-therapeutic-context-social/docview/1979167517/se-2

Janos, P. M., & Robinson, N. M. (1985). Psychosocial Development in Intellectually Gifted Children. In F. D. Horowitz, & M. O’Brien (eds.), The Gifted and Talented: Developmental Perspectives (pp. 149-195). American Psychology Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10054-006

Kakavand, A., Kalantari, S., Noohi, S., & Taran, H. (2017). Identifying the Relationship of Parenting Styles and Parent’s Perfectionism with Normal Students’ and Gifted Students’ Perfectionism. Independent Journal of Management & Production, 8(1), 108-123. https://doi.org/10.14807/ijmp.v8i1.501

Kirdök, O. (2004). Olumlu

ve Olumsuz Mükemmeliyetçilik Ölçegi Gelistirme Çaliþmasi. [Tesis de

maestría, Universidad Çukurova].

https://toad.halileksi.net/olcek/olumlu-ve-olumsuz-mukemmeliyetcilik-olcegi/

Lavrijsen, J., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Verschueren, K. (2020). Is Intelligence Related to Perfectionism? Multidimensional Perfectionism and Parental Antecedents among Adolescents Across Varying Levels of Cognitive Ability. Journal of Personality, 89(4), 652- 671. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12606

Leana-Tascilar, Z., & Kanli, M. (2014). Investigation of Perfectionism and Self–Esteem Scores of Gifted and Average Students. Ankara Universitesi Egitim Bilimleri Fakultesi Dergisi, 47(2), 1-20.

Madigan, D. J. (2019). A Meta-Analysis of Perfectionism and Academic Achievement. Educational Psychology Review, 31, 967-989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09484-2

Mayer, R. E. (1983). Pensamiento, resolución de problemas y cognición. Paidós Ibérica.

Mofield, E. L., & Parker, M. (2018). Mindset Misconception? Comparing Mindsets, Perfectionism, and Attitudes of Achievement in Gifted, Advanced, and Typical Students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 62(4), 327-349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986218758440

Molero, C., Esteban, C., & Saiz, E. (1998). Revisión histórica del concepto de inteligencia: una aproximación a la inteligencia emocional. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 30(1), 11-30.

Mudrak, J. (2011). ‘He was Born that Way’: Parental Constructions of Giftedness. High Ability Studies, 22(2), 199-217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2011.622941

National Association for Gifted Children. (2019, July 10th). A Definition of Giftedness that Guides Best Practice. https://eric.ed.gov/?q=source%3A%22National+Association+for+Gifted+Children%22&id=ED600145

Navarro-Saldaña, G., Flores-Oyarzo, G., &

González, M. -G. (2022). Estudiantes con alta capacidad: explorando su

distribución según tipo de establecimiento educativo. LIBERABIT. Revista Peruana de Psicología, 28(1), e500. https://doi.org/10.24265/liberabit.2022.v28n1.02

Ogurlu, U. (2020). Are Gifted Students Perfectionistic? A Meta-Analysis. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 43(3), 227-251. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353220933006

Ozdogan, D., & Akgul, S. (2023). Emotional Intelligence and Perfectionism among Gifted and Non-Identified Students. International Journal of Emotional Education, 15(1), 105-118. https://doi.org/10.56300/LAGP3672

Parker, W. D., & Mills, C. J. (1996). The Incidence of Perfectionism in Gifted Students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 40(4), 194-199. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698629604000404

Parker, W. D., Portesová, S., & Stumpf, H. (2001). Perfectionism in Mathematically Gifted and Typical Czech Students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 25(2), 138-152. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235320102500203

Patti, J., Brackett, M.

A., Ferrándiz, C., & Fernando, M. (2011). ¿Por qué y cómo mejorar la

inteligencia emocional de los alumnos superdotados? Revista electrónica interuniversitaria de formación del profesorado,

14(3), 145-156.

Plominski, A. P., & Burns, L. R. (2017). An Investigation of Student Psychological Wellbeing: Honors Versus Nonhonors Undergraduate Education. Journal of Advanced Academics, 29(1), 5-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202x17735358

Prieto, M. D., Ferrándiz, C., Ferrando, M., Sáinz, M., Bermejo, R., & Hernández, D. (2017). Inteligencia emocional en alumnos superdotados: un estudio comparativo entre España e Inglaterra. Electronic Journal of Research in Education Psychology, 6(15). https://doi.org/10.25115/ejrep.v6i15.1288

Renzulli, J. S. (1994). New Directions for the Schoolwide Enrichment Model. Gifted Education International, 10(1), 33-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142949401000108

Roedell, W. C. (1986). Socio-Emotional Vulnerabilities of Young Gifted Children. Journal of Children in Contemporary Society, 18, (3-4), 17-29. https://doi.org/10.1300/J274v18n03_03

Sastre-Riba, S., & Fonseca-Pedrero, E. (2019). Perfectionism and High Intellectual Capacity. Gifted Child Today, 79(1), 33-37. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85061865379&partnerID=40&md5=f33ebf8d2568945c17b767bf3dcaedf5

Sastre-Riba,

S., Fonseca-Pedrero, E., & Ortuño-Sierra, J. (2019). From High Intellectual Ability to Genius: Profiles of Perfectionism.

Comunicar, 27(60), 9-17. https://doi.org/10.3916/c60-2019-01

Schuler, P. (1994). Goals and Work Habits Survey [unpublished instrument]. University of Connecticut.

Schuler, P. A. (2000). Perfectionism and Gifted Adolescents. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 11(4), 183-196. https://doi.org/10.4219/jsge-2000-629

Silverman, L. K. (1997).

The Construct of Asynchronous

Development. Peabody Journal of Education,

72(3- 4), 36-58. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956x.1997.9681865

Simonton, D. K. (2003). An interview with Dr. Simonton. In J. A. Plucker (ed.), Human intelligence: Historical Influences, Current Controversies, Teaching Resources.

Speirs, K. (2007). Perfectionism in Gifted Students: An Overview of Current Research. Gifted Education International, 23(3), 254-263. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142940702300306

Speirs, K., & Finch, H. (2006). Perfectionism in High-Ability Students: Relational Precursors and Influences on Achievement Motivation. Gifted Child Quarterly, 50(3), 238-251. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698620605000304

Sternberg, R. J. (2012). Intelligence. In Handbook of Psychology, Second Edition (eds I. Weiner and D. K. Freedheim). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118133880.hop201009

Stricker, J., Buecker, S., Schneider, M., & Preckel, F. (2019). Intellectual Giftedness and Multidimensional Perfectionism: A Meta-Analytic Review. Educational Psychology Review, 32(2), 391-414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09504-1

Stoeber, J., & Rambow, A. (2007).

Perfectionism in Adolescent School Students:

Relations with Motivation, Achievement, and Well-Being. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(7),

1379-1389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.015

Subotnik, R. F., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Worrell, F. C.

(2011). Rethinking Giftedness and Gifted Education. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12(1), 3-54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100611418056

Terry-Short, L. A., Owens, R. G., Slade, P. D., & Dewey, M. E. (1995). Positive and Negative Perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 18(5), 663-668. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)00192-U

Wang, K. T., Fu, C. C., & Rice, K. G. (2012). Perfectionism in Gifted Students: Moderating Effects of Goal Orientation and Contingent Self-Worth. School Psychology Quarterly, 27(2), 96-108. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029215

Yazici, H., & Altun, F. (2015). Gifted and Nongifted Students’ Perfectionism, School Motivation, Learning Styles and Academic Achievement. Croatian Journal of Education, 16(4), 1031-1054. https://doi.org/10.15516/cje.v16i4.559

Yi, S., & Kim, A. (2012). Construction and Validation of the Academic Perfectionism Scale. The Korean Journal of Educational Psychology, 26(4), 837-860.

Yi, S., & Gentry, M. (2021). Academic Perfectionism of High- Ability and High-Achieving Students in Mathematics and Science: Differential Relations by Identification Criteria of Giftedness. Roeper Review, 43(3), 173-186. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2021.1923592

Zeigler-Hill, V., & Terry, C.

(2007). Perfectionism and Explicit Self-Esteem: The Moderating Role

of Implicit Self- Esteem. Self

and Identity, 6(2-3), 137-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860601118850

Recibido: 24 de febrero de 2024

Aceptado: 18 de junio de 2024

Este es un artículo Open Access publicado bajo la licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional. (CC-BY 4.0)