https://doi.org/10.24265/liberabit.2023.v29n1.623

ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN

Expansion of Knowledge, Practice and Public

Policy with the ICD-11 for Psychologists and Mental Health Professionals: A Literature Review and Critical

Analysis

Luis

Hualparuca-Oliveraa,*

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2026-3524

Estefanía Paola Betalleluz

Palominoa

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6401-0185

aEscuela de Psicología, Universidad Continental, Huancayo, Perú

Autor corresponsal

Para citar este artículo:

Hualparuca-Olivera, L., & Betalleluz, E. P. (2023).

Expansion of Knowledge, Practice and Public Policy with the ICD-11 for Psychologists and Mental Health

Professionals: A Literature Review and

Critical Analysis. Liberabit, 29(1), e623. https://doi.org/10.24265/ liberabit.2023.v29n1.623

Abstract

Background:

Mental disorders are alterations in several functional

domains of human beings that trigger greater

morbidity and mortality if not adequately addressed. The International Classification of Diseases

11th Edition (ICD11) is a recently approved modern

global system to guide clinical

practice for these disorders and other conditions. State of the art:

Despite the imminent

implementation of this system in member states,

the guidelines on its

scientific basis, practice and importance in public health have been published

in a scattered manner, with a mainly psychiatric medical target audience, hence, it is necessary to unify these

guidelines in a single text. Therefore, the objective of this review

was to analyze three

associated aspects: (a) current knowledge of the subject, (b) its application in psychological practice,

and

(c) reflection on the implications for public health policies. To do this, these aspects

were divided into 10 sections with

the most relevant topics, and examples have been described to facilitate their use and comments to promote their understanding. Conclusions: This paper presents a review that comprehensively addresses knowledge- practice-policy triad of mental disorders

of the ICD-11.

Keywords: ICD-11; mental disorders; psychology; clinical practice; public health.

Resumen

Antecedentes: los trastornos mentales son alteraciones en varios dominios funcionales del ser humano que desencadenan mayor morbilidad y mortalidad si no se abordan adecuadamente. La clasificación internacional de enfermedades en su 11.a edición

(CIE-11) es un sistema global y moderno recientemente

aprobado para guiar la práctica clínica ante estos trastornos y otras condiciones. Estado del arte: a pesar de la inminente implementación de este sistema en los estados miembros, las guías sobre su base científica,

práctica e importancia en la salud pública se han publicado de manera dispersa, con una audiencia objetivo principalmente medica psiquiátrica; y de este hecho parte la necesidad de unificar estas guías en

un único texto. Por ello, el objetivo de esta revisión fue analizar

tres aspectos asociados: (a) el conocimiento actual del tema, (b) su aplicación en

la práctica psicológica y

(c) la reflexión sobre las implicancias en las políticas de salud pública. Para ello, estos aspectos

se han divido en 10 secciones con los tópicos más relevantes, y se han descrito ejemplos

para facilitar su uso y comentarios para promover su comprensión. Conclusiones: este artículo presenta

una revisión que aborda integralmente la triada conocimiento- práctica-política de los trastornos mentales de la CIE-11.

Palabras clave:

CIE-11; trastornos mentales;

psicología; práctica clínica; salud pública.

Mental disorders consist of significant disturbances in thinking, emotional

regulation, or behavior (World Health Organization [WHO], 2022e). Although there are effective

alternatives for the prevention and

treatment of these conditions, a large

proportion of the population does not have access to effective care. According to the WHO (2022e), one in every eight people in the

world lives with a mental disorder

by generating disability, increased morbidity and

mortality. Classifications have been designed and revised for more than a century

to guide clinical practice and

improve communication between mental

health professionals and researchers (Fiorillo

& Falkai, 2021); all this, through widely accepted descriptions of mental disorders

that allow an evaluation and

diagnosis framework for adequate intervention

of the patient (Fiorillo & Falkai,

2021; Lindmeier, 2022).

Although there are several

used classification systems

(such as the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders 5th edition,

text revision [DSM-

5-TR], the Hierarchical Taxonomy of

Psychopathology [HiTOP], the Research

Domain Criteria [RDoC] and the Systems

Neuroscience of Psychosis [SyNoPsis]), there is no doubt that the most important is the International

Classification of Diseases (ICD;

Columbia Psychiatry, 2022)

because of its development and global

applicability; which

not only describes

mental disorders, but also all known diseases, possible causes and determination of their manifestation

and joint influence (WHO; 2022d). The

ICD revisions have taken into account (vertical) compatibility with the entire WHO family of international classifications and mutual (horizontal)

compatibility with the United Nations

(UN) families of international classifications (Guggenheim, 2013); which together allow a

multidisciplinary and multisectoral approach to mental disorders

(Hualparuca-Olivera et al., 2022). ICD-11,

recently approved for use (WHO,

2022c), includes mental disorders in one of its chapters

called Mental, Behavioral

or Neurodevelopmental Disorders

(ICD-11 MBNDs). This chapter presents the challenges

and opportunities for health professionals, administrators, and authorities of member states

in this new era.

In this sense, the current

practice of clinical

psychologists requires an understanding of the ICD- 11 standards to be able to code properly and conduct a complete evaluation (i. e., case formulation) in order to improve mental health of their patients (Stein et al., 2020). Because the ICD-11 does

not fully describe the causality of

the diagnoses, it does not aim at

what underlines a symptom, for therapeutic purposes,

but rather at the phenomenology of each symptom

(Kountouras & Sotirgiannidou, 2022; Stein et al., 2020). For that reason, it is

possible that the assigned ICD-11

diagnosis serves as a first route to design

an evidence-based intervention specific to a

disorder, if this is unique and has a great adjustment to

the clinical manifestations of a

patient (very atypical situation);

otherwise, psychologists will have to rely on

case conceptualization strategies with a more in- depth evaluation to plan a treatment according to the individual needs of the user (The Psychology Practice, 2021). Certainly, this last route allows

clinicians to intervene in the

symptoms of a patient with relative independence

from the diagnostic categories of the ICD-11-MBNDs.

From a biopsychosociocultural

approach, mental health practice is

often based on the knowledge and integration of psychotherapeutic theories and techniques to define the complex interactions between health factors (Hooley et al., 2021). Therefore, by integrating the lifespan and stepwise

approach, and recognizing the natural course of the disorder

(Gaebel et al., 2022;

Stein et al., 2020; Vujnovic et al., 2021),

psychologists must analyze the relationship of personal history; which includes biopsychosociocultural risk and

protective factors, whether distal (past) and/or proximal (current) (Hooley et al., 2021), with clinical manifestations of the disorder

(including current behavior).

In addition, psychologists must

measure the impact of the disorder on social impairment and

assess subjective personal

experiences (e. g., distress; see Regier et al., 2020). As they do so, it is pertinent to consider the cultural characteristics

(geography and language) of patients (Sharan & Hans, 2021), establish a differential diagnosis of the disorder and an etiological diagnosis of the deterioration; and define a treatment guideline according to the needs of the patient

(Kielkiewicz, 2019). Psychologists must know

and apply

psychiatric, psychological (and

legal, if required) terminology in addition to using the standard methodologies

for research (and teaching) with the best possible

evidence to guide (and even lead) public policies

(see Saxena et al., 2012). An

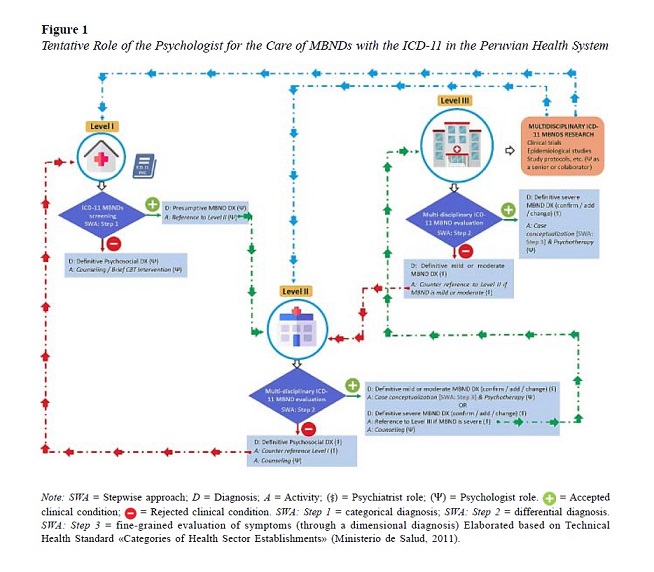

overview of the role that Peruvian

psychologists would play in caring

the MBNDs with the ICD-11

is shown in Figure 1.

Consequently, this paper offers a review to address the science-praxis-policy triad by using understandable terminology for psychologists. In addition, to reinforce collaborative work in this review for the sake of ICD-11

implementation, terminology compatible with other professions that

work closely with mental health was also used. Certainly, the practice

and public policies analyzed in this review is

focused on the Peruvian reality, but they can be adapted to other realities.

ICD is the international standard for

systematic recording, reporting, analysis, interpretation, and comparison

of mortality and morbidity data (Lindmeier & Joi, 2018; Reed, 2010). The 11th revision is the result of a collaboration between health professionals,

statisticians, epidemiologists,

encoders, translators,

experts in classification and information technology (IT) from around the world (Lindmeier & Joi,

2018). As Youmans (2022) mentions, the ICD- 11 is a scientifically rigorous product that accurately reflects contemporary health and clinical practice and represents a significant improvement on

previous revisions. In this sense, the objectives

of the implementation were

(1) to guarantee that the ICD- 11 works in an electronic

environment, (2) to provide a multipurpose classification by guaranteeing consistency and interoperability between

different uses, and (3) to provide

an international and multilingual

reference standard which allows scientific

comparability (WHO, 2022d).

The ICD-11 classification system

integrates 26 chapters, including chapter 6

about mental, behavioral, or neurodevelopmental disorders, and includes

a supplementary section for

functioning assessment, referring

to groups of diseases with more than 17 000 flexible alphanumeric codes, more than 120 000 coded entities and with the indexing of more than 1.6 million clinical terms to these coding entities (Pezzella, 2022;

Regier et al., 2020). These codes range from 1A00.00 to ZZ9Z.ZZ including a letter as the second character to differentiate from the ICD-10

(Hyeji et al., 2022). As Caux-Harry

(2018) mentions, ICD-11 changes category

codes from 3 characters (characters to the left of the decimal)

to 4, with an alphabetic character in the second

position and a number always in the third position; thus, the first character of any code symbolizes the chapter number. For

chapters 1 to 9, the first character

of the code corresponds to the chapter

number, whereas for chapters 10 to 26, the first character is a letter (Caux-Harry, 2018). Consequently,

all codes of the same chapter always start with the same character; furthermore, the number of characters in the code varies from 4 to 7 (International Federation of Health Information Management Associations [IFHIMA], 2021).

The basic

structure, characteristics and

substantial changes of ICD-11 compared

to its previous revision are better described in Hyeji et al. (2022).

The ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (ICD-11 MMS) has two

online/offline systems: (a) an online browser which is an enlarged

electronic version of a tabular list

in English, Arabic, Spanish, French,

Russian, and Chinese (see Harrison et al., 2021);

(b) a coding tool that is used in a

similar way to the alphabetical

index in previous revisions, but with several

enhancements to facilitate accurate, simple, and fast coding;

(c) a reference guide describing an introduction to the context, components, and intended

use (WHO, 2022d);

and (d) a maintenance platform

–WHO-FIC Maintenance Platform–, where modifications or

additions can be proposed (IFHIMA,

2021). The ICD-11 is currently used in 35 countries

(WHO, 2022c) and several decades will possibly go by until there

is a new review (Regier et al., 2020).

The ICD-11 has a dimensional approach that allows adding specific

categories pertaining to current symptoms, severity, and course of

illnesses to better track changes over time. As mentioned by Lindmeier and Joi (2018), this classification system

contains the WHO nonproprietary names for drugs, clinical documentation,

allergology, reimbursement, primary care, causes of death, cancer registry,

patient safety, dermatology, pain documentation, and data dictionaries for the guidelines related to ICD-11. Additionally, in response to the

COVID-19 pandemic, codes have been developed

to confirm the diagnosis, categorize it as a cause of death, categorize post-disease problems, document the vaccination procedure, and identify any negative impacts on them,

among others (Harrison et al., 2021; Lindmeier & Joi, 2018).

As mentioned by Reed, Sharan, et al.

(2018), an ideal classification system ensures reliable diagnosis of mental disorders. Moreover, it can be clinically

useful and applicable worldwide

(Keeley, 2016). Thus, a proper identification of a person’s mental health needs is ensured to provide adequate and cost-effective treatment

(Reed, Sharan, et al., 2018). With this objective, a

series of studies and reviews have been carried

out by psychiatrists and psychologists when designing chapter 6 of the ICD-11: mental, behavioral, or neurodevelopmental disorders (ICD-11

MBNDs; Keeley, 2016; Keeley et al., 2016; Kulygina et al., 2021; Reed, Keeley, et al., 2018; Reed, Sharan, et al., 2018); which resulted in a preliminary product,

the ICD-11 Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines (ICD- 11 CDDG).

Chapter 6 of the ICD-11

contains 21 sets

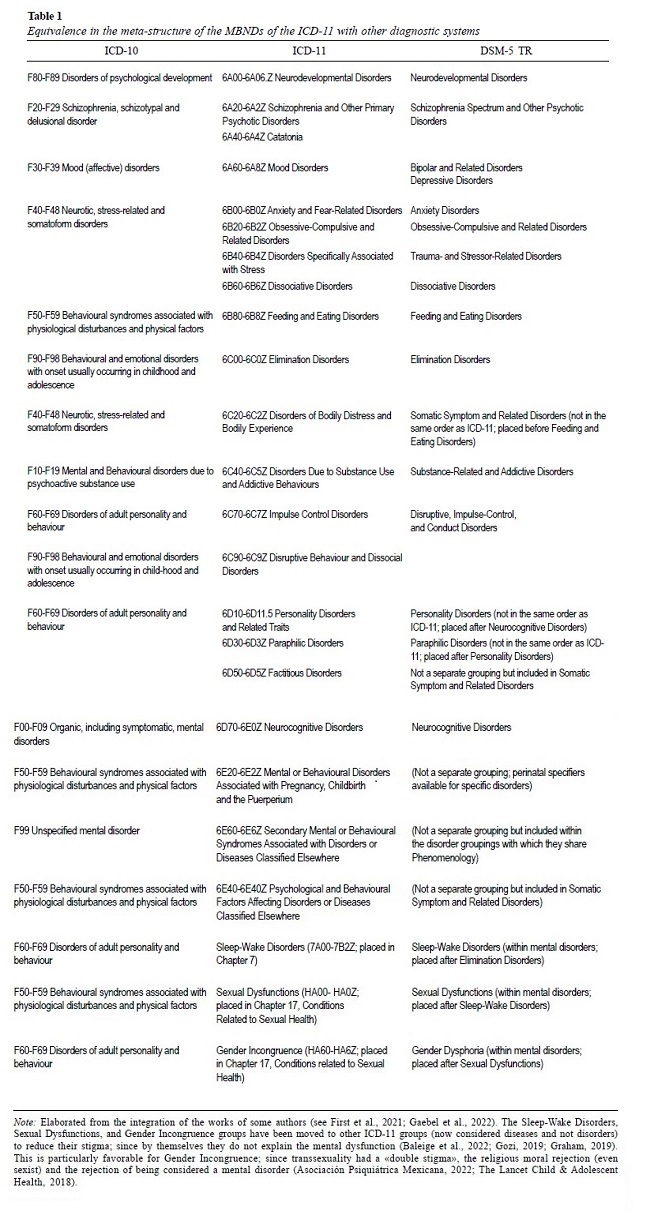

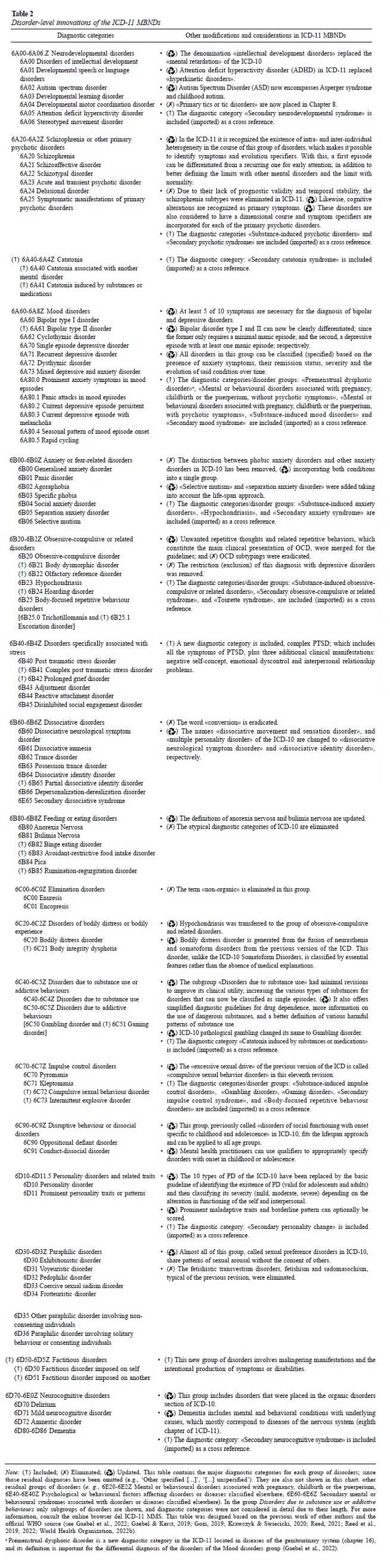

of diagnostic categories for Mental, Behavioral, or Neurodevelopmental Disorders - MBNDs (see Table

1). The ICD-11 CDDG contains information about

each of the groups of diagnostic categories concerning the

ICD-11 MBNDs in addition to the statistical version of this chapter, which is displayed on their offline/online systems alongside the other medical

conditions listed above.

Owing to a worldwide partnership of healthcare

professionals, this document was created as

a project to assist in the diagnosis of the practice of mental health professionals, and it was accessible until 2021 in the global clinical

practice network (GCPN).

The goals of the ICD-11 related to CDDG

were to: (a) collect data and information systematically; (b) use a longitudinal approach rather than a

transversal conceptualization; and (c) concentrate on more practical indices such as comorbidity and

long-term disability (Vujnovic et al., 2021). The

final product of this project, also published in the GCPN, replaced the ICD-11 CDDG and was called the ICD-11 Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic

Requirements (ICD-11 CDDR). The

ICD-11 CDDR contains, in addition

to the aforementioned diagnostic guidelines, considerations related to the limit of normality

(threshold), characteristics of the course, development,

culture, sex and/or gender, and the

limits with other disorders and conditions (differential diagnosis). The ICD-11 CDDR is not part of a separate

section or book but is implemented in the ICD-11

for MMS itself as part of the structure of its

diagnostic categories.

For centuries,

mental disorder classification

systems have focused more on inter-rater reliability than on the

clinical usefulness of diagnostic categories, resulting in clinicians who do not easily

understand or apply diagnoses, which

makes it difficult to identify and adequately

treat people with mental disorders (Keeley, 2016). In the ICD-11 MBNDs chapter, an attempt was made to simplify this situation by eliminating or merging categories that were not useful, and flexible guidelines were established to improve their cross-cultural

applicability (Keeley, 2016). The

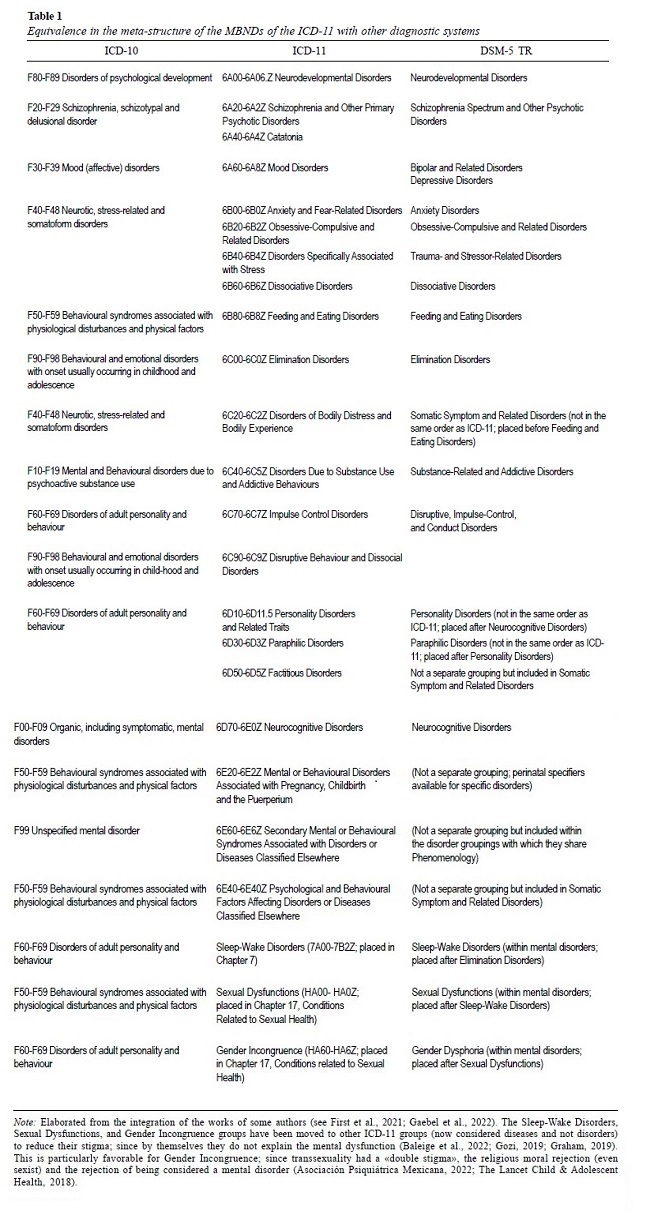

structural changes in this chapter were primarily:

(a) the elimination of disorders of

sleep and wakefulness and disorders related

to sexual health, currently grouped into two

separate chapters recently integrated (Gozi, 2019); and (b) the addition of various new diagnoses (see Gaebel et al., 2022).

These new mental

disorders were added

to (i) optimize the usefulness of morbidity statistics; (ii) facilitate the identification of clinically important

but misclassified mental disorders

to provide appropriate management; and (iii) promote the investigation of more effective treatments (Reed et al.,

2022). For more information on the amendments at the disorder

level, see Table 2.

Other

additional changes correspond to the dimensional

perspective that is implemented

within the diagnostic categories because the evidence

has shown that MBNDs

represent, for the most part, the interaction of latent dimensions (Columbia Psychiatry, 2022;

Reed, 2021; Roessner et al., 2016). This dimensional perspective promotes a recuperative approach to the care of these conditions

instead of treating them as chronic (Regier et al., 2020), labeling and generating stigma towards patients (Asociación Psiquiátrica Mexicana, 2022). Likewise, it offers the opportunity

to intervene in specific problems with specific

interventions, according to the complexity level

(comorbidity) of the cases, thus also defining

health care needs (Reed, 2021).

Evidence has shown that: (a) the clinical

manifestations of adult disorders occur similarly in childhood; (b) child and adult disorders appear to be continuous,

as many young adults with psychiatric disorders (neurodevelopmental, emotional, and behavioral) have had psychiatric diagnoses

in adolescence (Garralda, 2021); –e. g., separation anxiety disorder or avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder are diagnosable in both children and adults–. Based on this evidence

and in line with the taxonomy proposed in the DSM-5, the ICD-11 working group

made the decision

to modify the location of childhood mental

disorders and merge them into ICD-11 categories. Thus, all diagnoses

offer a lifespan approach (i. e., with a longitudinal focus on human development) and an explicit set of instructions about the ways in which manifestations vary by age (Garralda, 2016).

The ICD-11 MBNDs category groups

–unlike the Kraepelinian organizational structure (Gozi, 2019)– begin with diagnoses that reflect disturbances manifesting early in life development (Garralda, 2016); e. g., 6A00-6A06.Z neurodevelopmental disorders,

and 6A20-6A2Z schizophrenia and other primary

psychotic disorders, followed by diagnoses that

manifest more frequently in adolescence and early adulthood,

such as 6A60-6A8Z mood disorders, 6B00-6B0Z anxiety and fear-related

disorders; and diagnoses relevant to

adulthood and later life, such as 6D70-6E0Z neurocognitive disorders (Gozi, 2019; Regier et al.,

2020). Within this overall framework, each

disorder now aims to describe variations in children’s

presentations, and children’s most typical diagnostic

categories are those appearing in the first

years of life, neurodevelopmental disorders, disruptive behavior, and dissocial disorders (Garralda, 2016).

Neurodevelopmental disorders

mainly include: 6A00 disorders of intellectual

development, 6A01 developmental speech or language

disorders (including alterations related to language

and speech sound/fluency), 6A02 autism spectrum disorder, 6A03 developmental

learning disorder, 6A04 developmental motor coordination disorder, 6A05

attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder, 6A06 stereotyped movement disorder,

and other residual diagnostic categories. These

disorders, which may be comorbid, have an early

onset in a person’s life with the potential to

induce lifelong impairments (Roessner et al.,

2016). In addition, their symptoms

are characterized by delays,

excesses, or deviations in the fulfillment of the maturation achievements of normal

development. Autism spectrum

disorders (ASD), –which include autism, Asperger

syndrome, and disintegrative and generalized developmental disorders–, comprise a dyad of alterations in social communication and restricted repetitive behaviors (Garralda, 2016).

It is recognized in ICD-11 that

individuals with ASD frequently exhibit

simultaneous degenerations in language

and intellectual function, which probably generate the loss of some skills

(previously acquired) without

the presence of a neurological disorder (Garralda, 2021). These limitations should be considered

for the scope of multidisciplinary support, treatment planning, and selection

of effective individualized interventions. Likewise, specific language disorders cause significant limitations in the ability to communicate and can also be

classified based on the main focus of

the alteration, either in receptive language

or in expressive (pragmatic) language. A possible guideline for the

differential diagnosis of specific

language disorders and ASDs is the

lack of repetitive and restricted interests that characterize the latter (Garralda, 2016).

On the other hand, disruptive behavior and dissocial disorders mainly include 6C90 oppositional defiant disorder (with qualifier/subtype: with and without chronic irritability-anger), and 6C91 conduct- dissocial disorder (with qualifier/subtypes: childhood onset and adolescence; and it is the

earliest onset with a poorer prognosis). Both disorders have a qualifier with limited prosocial emotions

in children who are identifiable, relatively stable, and linked

to a more severe, aggressive, and stable pattern

of antisocial behavior.

Intermittent explosive disorder, kleptomania, and pyromania may be classified in this section if they are chronic; or in a

separate group of impulsive

disorders, if they are episodic (Garralda, 2021).

To date, findings from field studies

conducted in children and

adolescents have confirmed adequate levels

of validity and reliability of the CDDR for diagnosing

oppositional defiant disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder (ADHD), mood disorders,

anxiety, and fear-related disorders, reinforcing its global

applicability (see e. g., Robles et al., 2021).

The differences between the ICD-11 and

DSM- 5-TR (American Psychiatric

Association, 2022) are intentional because they are directed toward different goals.

This is because

the former is the product

of the collaborative work (non-profit) of experts from different professions (in addition to authorities) from 159 member states; while the latter configures a (commercial) franchise of the work of experts from a single

profession and from a single country (Asociación Psiquiátrica

Mexicana, 2022; Columbia Psychiatry, 2022). The DSM-5-TR has a more research-oriented (and less practice-oriented) approach

because it has rigid diagnostic criteria (e. g., criteria A, B, etc.), which are expected to maximize the

reliability of diagnostics in

different environments (Appelbaum, 2017; Bach et al., 2022; Stein et al., 2020). In contrast,

the MBNDs of the ICD-11 have a more pragmatic approach because they incorporate flexible diagnostic

guidelines (vignettes), considering in a deeper way the variability of diverse cultures and

limitations of the different levels

of health care, –even in low-resource settings– (Appelbaum, 2017; Bach et al., 2022; Stein

et al., 2020).

The chapter groups of the ICD-11 MBNDs

are listed in Table 1, which also

includes a comparison with the DSM-5-TR meta-structure; –for further details on the differences and similarities in diagnosis between ICD-11 MBNDs and DSM-5-TR

consult First et al. (2021) and

O’Brien (2022)–. In general, the comparability

of the structure of the two classifications

can be considered a success of the harmonization

efforts between the WHO and APA. Some structural

differences reflect ICD-wide conventions related to residual categories and mental disorders associated with other underlying illnesses.

The discussions in

which the WHO, the Advisory Group, and the various

Working Groups took part resulted in other differences, such as those regarding the diagnosis and treatment of children

with chronic irritability and anger,

compulsive sexual behavior disorder, personality disorders, substance use/ substance

dependence, and somatoform disorders. Another

distinction is that the new chapters of the ICD-11 include the classification of «organic» and

«non-organic» components of sleep-wake disorders, problems relating to sexual health, and gender identity in ways that are connected with the most

recent research and clinical

practice (O’Brien, 2022).

Regier et al. (2020) stated that one of the similarities between the two diagnostic systems is the incorporation of a dimensional approach

for some disorders within their categorical system. The debate

between the psychoanalyst’s

approach to the dimensionality

of mental disorders, and the discrete categorization of these conditions from the neo- Kraepelinian approach, can lead to a better understanding of the disorders through the

description of the etiological factors,

characteristics, and clinical

course of the disease, supplemented with symptom scores. Accordingly, for some ICD-11 and DSM5- TR diagnoses, dimensional expansions regarding severity,

course, and specific

symptoms were added.

Some examples of ICD-11 include autism spectrum disorders (ASD), personality

disorder, depressive or bipolar

disorders, and primary psychotic disorders (Alves et al., 2020; Gaebel et al., 2022); while in the DSM-5 TR, they are autism spectrum

disorders (ASD), attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, bipolar

disorder, and major depressive disorder (Regier et al., 2020).

According to Michael B. First, co-chair and editor of DSM-5-TR, the differences

between ICD-11 and DSM-5 TR provide four main advantages and disadvantages (as cited in O’Brien, 2022): (a) it enables classifications to be improved

to satisfy user group

needs; (b) it also supports growing clinical

research validity over time; (c) it encourages frequent evaluation of the best nosological approaches; (d) finally, opportunities were created for those working

on the development of diagnostic and measuring tools. However,

these variations are disadvantageous because:

(ii) they make it more difficult to gather and report health statistics in countries that use the DSM;

(ii) they make it more difficult to compare the findings

of studies that were assessed using various systems;

(iii) they make it more difficult to evaluate

and approve drugs for patients

whose medical indications were prescribed using various

systems; and (iv) they add to the

workload for those who create

diagnostic tools and measurements (O’Brien,

2022).

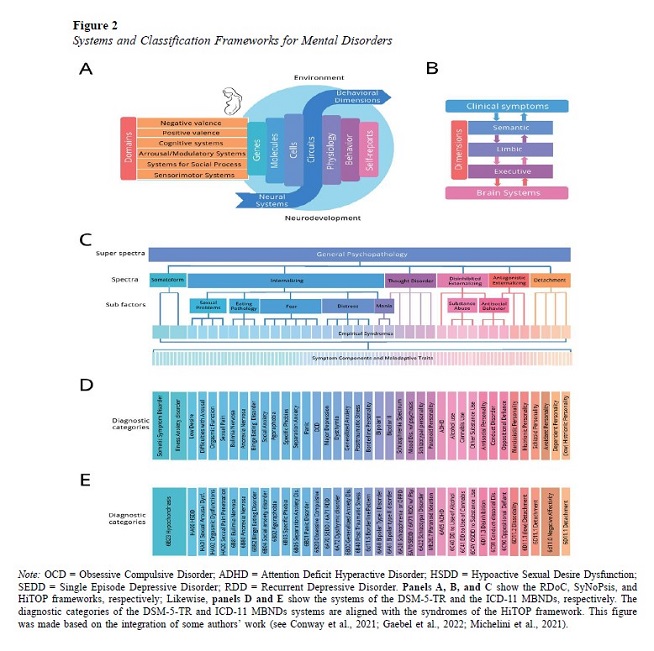

In recent years, three approaches have been introduced

in psychiatric nosology: HiTOP, RDoC and SyNoPsis –see Figure 2 for more detail on the constructs of these approaches–. As Gaebel et al. (2022)

mentioned, these frameworks were developed from a dimensional perspective to enable more accurate and nuanced knowledge of mental

disorder assessment and diagnosis

of mental conditions, rather than categorical descriptions that

reduce the validity and reliability of mental disorders

(Strik et al., 2017). The first of them (HiTOP),

designed by the HiTOP Consortium, seeks a classification based on the multivariate phenotype of clinical conditions; and the remaining two, –RDoC from the National

Institute of Mental Health in the USA (NIMH) and SynoPsis from the Bern University

Hospital of Psychiatry

in Switzerland– an etiological explanation based on the neurobiology and pathophysiology of these conditions.

Currently, these three frameworks have

deficits in terms of their global and clinical applicability (utility) because

they are: complex

for practice and culturally variable (Gaebel et al., 2022; Sharan & Keeley, 2018), –mainly in the case of HiTOP–; and practically

inaccessible and do not have convincing evidence of the neurobiology-psychopathology association (Gaebel et al., 2022;

Regier et al., 2020),

–mainly in case of RDoC and SynoPsis–. In the future, if science

demonstrates a harmonization of the RDoC or

Synopsis units of analysis with syndromic manifestations, these neurobiological frameworks may be incorporated into future versions

of the ICD; –only if they have evidence

of acceptable diagnostic validity and are practical in

routine settings (Gaebel et al., 2022)–. Gaebel et al. (2022) mention that HiTOP can be incorporated, but only in

specialized mental health units; however,

given its complexity, it will

not be able to offer substantial changes in the classification of these systems. Recent preliminary evidence

has rejected HiTOP as complex to use (see

Balling et al., 2023); however, more study is still needed

on this subject.

As mentioned by some authors,

a potential problem

with current categorical classification systems is that they were designed

for global applicability in

various settings, which could lead to the

loss of construct validity (Gaebel et al., 2022; Maercker, 2022). Complex frameworks such as RDoC or HiTOP are suitable for research purposes, while the categorical classification system

in ICD-11 provides greater clinical utility (Gaebel et al., 2022; Regier et al., 2020). For this reason, researchers often prefer

detailed dimensional assessments; while primary care mental health professionals need diagnostic categories that are easy to understand and communicate (e. g., referrals and counter-referrals) (Gaebel et al., 2022). However,

the strengths of these dimensional frameworks can already be

used by the member states,

including Peru.

Gaebel et al. (2022) emphasized that to ensure that future versions of the ICD meet the needs of different user groups, it is pertinent that a gradual procedure for diagnosis (i. e., a stepwise approach) be implemented. In this approach, each diagnostic step

describes the patient’s psychopathology in greater detail.

In step 1 of

the diagnosis, a patient’s symptoms

can be classified into broad

diagnostic categories, as suggested in the primary care version of ICD-11, –e. g.,

for the identification and management of mental disorders in the first level of care of Peruvian health establishments (levels of care from I-1 to I-4 of the establishments

of the Ministry of Health [MINSA])–. In this step, patients suffering from a degree of distress who require additional

diagnostics and specialized

interventions can be

identified. In step 2, a more

specific differential diagnosis can be made. The ICD-11

CDDR provides detailed

descriptions of the core symptoms of

disorders, boundaries

with normality, and guidelines for differential diagnosis. This step can be performed in

the second and third level of care (e. g., from II-1 to III-E of MINSA establishments). Once the disorder

has been identified and differentiated, reassurance, brief cognitive interventions can be performed for a

mild level of disorder severity.

Step 3 of the diagnosis enriches

categorical diagnoses with

dimensional assessments in research settings

and specialized interventions to pin down psychopathology; –e. g.,

also at the second and third level

of care (specialized care)–. Thus, the advantages of both approaches can be combined (e. g., for the diagnosis of schizophrenia or other primary psychotic disorders). Specifically, the result of each categorical diagnosis can be

complemented with a symptom profile

that provides specific

information about the domains involved. In this step, users with moderate and severe personality disorder can be cared for. In

moderate cases, brief cognitive

interventions, less intensive structured psychotherapies are used; whereas,

in severe cases structured

intense psychotherapies and medications are used (Mulder,

2012). Similarly, counter-referrals can be issued if mild or

subclinical levels of the disorder

are found. Bach and Simonsen (2021) mentioned

that the disorder severity configures a decision tool for clinical management and the intensity of required treatment (involving the need to establish epistemic trust, level of support approach and strength of the therapeutic alliance).

Consequently, with the stepwise approach, prompt communication based on diagnostic categories is promoted; and dimensional assessments will provide more nuanced profiles for contexts where

detailed dimensional information beyond the overall degree of severity is needed to inform treatment (e. g.,

psychotherapy) and research. The stepwise approach covers only some groups of disorders in

ICD-11. However, there is great

potential for enriching more categorical diagnoses

with dimensional symptom

profiles. For example, experts have recommended assessing all symptoms

of substance use disorders in the DSM-5-TR

on (at least) a 3-point

scale; initiative which can be implemented in later

versions of the ICD (Gaebel et al., 2022).

One should consider (a) genetic abnormalities, (b) brain

dysfunction and neuronal plasticity, (c)

hormonal and neurological

abnormalities, (d) neurotransmitters in the brain or other parts

of the central nervous system, and (e) temperament when examining biologically

based abnormalities for potential

diagnosis of any MBND ICD-11 (see Hooley et al., 2021). The ways

in which the environment can

influence the genotype (genotype-environment correlations), the ways in which the genotype can

influence the phenotype, and the ways in which genetic vulnerabilities can

influence the development of mental disorders (environment-genotype interactions) are some of the proposed

objectives in the biological

investigation of MBNDs (Hooley et al., 2021; Kring

& Johnson, 2021). Adoption, twin,

and family history studies are all ways to examine how much genetic and environmental factors

play a role. However, recent research has concentrated on employing

linkage analysis and association studies to identify the precise position of genes that contribute to mental diseases

(Hooley et al., 2021).

According to Hooley et al. (2021), the

results of these studies showed that

there are 1000 (distinct) genes that influence with a certain degree of vulnerability

(diathesis) to schizophrenia; and some of

these genes are also found in severe depressive disorder, 6A02 autism

spectrum disorder (ASD), bipolar disorder and in 6A05 attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder

(ADHD). On the other hand, studies of

neuronal plasticity have shown that

the genetic makeup of brain development is not fixed

as existing neural circuitry can be often modified based on experience. Additionally, various neurotransmitters

(primarily serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, glutamate, and gamma aminobutyric acid) and hormonal abnormalities (primarily the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal, axis with

activation of corticotrophin,

adrenocorticotropic, epinephrine [adrenaline], and cortisol) contribute to the development of different mental disorders

because of their effects on specific

areas of the brain and body.

Likewise, temperament –strongly

influenced by genetics– configures the set of characteristics for reactions and self-regulation to

environmental stimuli. Temperament

also constitutes the basis of adult personality and influences vulnerability to various disorders

(Hooley et al., 2021).

Psychologists must consider these

vulnerabilities mainly at the time

of case conceptualization, and treatment

planning. To control the associated acute symptoms of these vulnerabilities, immediate psychiatric care is crucial –e. g., the above- mentioned

schizophrenia or ADHD, which are more strongly associated with alterations in biological domains

as established by the organization of ICD-

11 MBNDs through the lifetime approach–.

Additionally, in specialty care health centers (e. g., hospitals), patients with life-threatening, degenerative, and/or chronic medical

conditions (e. g., 2C61 Invasive

breast carcinoma) may develop psychiatric conditions (e. g., 6E62.2 Secondary mood syndrome, with mixed symptoms). In these circumstances, multidisciplinary and coordinated work between doctors, nurses, psychologists, and

clinical social workers is needed to achieve adequate

knowledge of the disease and develop coping strategy and adherence

to psychological and medical treatment (Semple & Smyth, 2019).

The ICD-11 stems from the medical model, where the disorder is identified solely through its symptoms, and the typical treatment is to eliminate them through medication, without the need

to identify and treat its causes. If

only this approach is used, mainly for severe

levels of the disorder, it is possible that the patient develops dependence on the medication and the symptoms reappear

once it is discontinued (Kielkiewicz,

2019). For example, a meta-analysis showed

that a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy produces

more effective outcomes

against major depressive disorder than each of these treatments applied individually (i. e., monotherapy; Kamenov et al., 2017). Although there is some interpretation bias, another umbrella

review also demonstrated the superiority of combined

treatment in cases of ADHD, complex

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

and Social Anxiety compared to monotherapy (Leichsenring et al., 2022).

Given this, the psychological interpretation of the patient’s

condition, through psychological theories, is important for the psychotherapeutic approach (Peterson, 2009).

Certainly, science cannot find

replicability of the results to

identify genetic and environmental agents, or

their degree of influence in the development of a mental condition; consequently, these cannot be generalized. However,

based on the individual psychological evaluation,

conceptualization of the case, psychodynamic definition of the problem, functional analysis and other strategies

used by the psychologist, it is possible

to find the causal components

(or at least the most influential central components

in the deterioration) for the development, maintenance, and exacerbation of other symptoms

or signs of the disorder(s)

(Kielkiewicz,

2019). Intervening in these causal agents from the individual intervention, and progressively with group therapies, pharmacological treatment can be enhanced,

and eventually discontinued without fear of relapse.

A psychologist, unlike a psychiatrist –as is traditional– must delve deeper into the patient’s

problem. Psychiatrists often have a high demand for patients (often

continuators) and therefore, reduce

their attention

time (Evans et al., 2013; Guggenheim, 2013); which probably also affects rapport (Patel et al., 2017). Additionally, patients may feel less

stigmatized and better understood in

a psychological consultation because

psychologists, unlike psychiatrists, assign fewer diagnostic categories to a patient (Evans

et al., 2013). According to Evans et al. (2013), these different perspectives on the patient’s mental

condition lie in main issues such as: theoretical perspectives, training, professional

activities, the services provided,

the served patient populations,

and health policies. The stigma must

certainly be of particular interest and care for psychologists to address and reduce its effects on patient

care.

Although both types of mental health practitioners are responsible for treating patients with compassion, empathy,

and dignity, psychological care produces more

relief than psychiatric consultation because of the emotional and therapeutic link that is created. Moreover,

in psychological care, people are not usually labeled as «depressed» or «schizophrenic», and active listening and other interview

techniques based on emotional reflection are used. Also, a feedback based on psychological theories

is carried out to obtain an understandable, assertive, and compassionate message

of the psychiatric condition.

Psychologists are aware of two fundamental problems: (a) Psychiatric diseases are severe forms of internal experience and behavior, due

to sadness, rage, and anxiety; which are common human emotions; (b) unlike other medical conditions (illnesses),

mental disorders generate more prejudiced and derogatory assumptions than other types of medical conditions (Miles, 2018). The

patient is not to blame for having

a disorder (Corrigan et al., 2014), and probably does not deserve to be

objectified with these adjectives.

Considering the role of the psychologist

for the management of diagnostic

categories of the ICD- MBNDs (see Figure 1), prevention would mainly lie in the adequate detection (presumptive

diagnosis) of the MBNDs, their subclinical levels and the psychosocial

factors present that affect the patient; this

is followed by a brief CBT approach or referral as appropriate. For this, the psychologist and health professionals at the first level of care

must receive training for proper management

of step 1 of the stepwise approach

(categorical diagnosis) using the ICD-11-PHC and ICD-11 MMS as a guide.

At the second level of care where confirmation of the clinical condition is required in

a precise and refined manner (steps 2 and 3 of the stepwise approach), the psychiatrist must assign the definitive diagnosis of the ICD-11 MBNDs

after a multidisciplinary evaluation

with the psychologist and/ or a nursing professional specialized in mental health

issues. This diagnosis must be complemented with a case formulation that includes the anamnesis, current

behavior, presentation of symptoms, subjective experience of the user and social functioning. After that, the psychologist will be able to establish the most appropriate therapeutic regimen for the

case (see e. g., Kramer, Eubanks, et al., 2022); being able to predict

the estimated time of therapy,

possible complications –e. g., abandonment of therapy, usual in patients with 6D11.5 Borderline pattern

(Arntz et al.,

2022; Iliakis et al., 2021); or refusal of therapy, typical

in patients with 6D11.2 dissociality in personality disorder or personality difficulty (Herpertz et al., 2022)–, possible acute

episodes and comorbidities with other conditions and/or mortality outcomes. These predictions will also provide

psychologists with possible

treatment/approach alternatives to initiate a change in the proposed

therapeutic scheme and improve the therapeutic alliance

(Kramer, Ranjbar, et al., 2022).

Likewise, the forecast extracted from

the case conceptualization will serve to establish distance

between the dates of home visits, or phone call tracking of the users. For example,

continuous (weekly)

tracking is preferable in patients with severe levels of a condition and suicidal intent –e. g., in cases

of patients with 6A71.4 recurrent

depressive disorder, current episode severe, with psychotic

symptoms / 6B41 Complex post-traumatic stress

disorder / 6D11.5 Borderline pattern

(Gelezelyte

et al., 2022)–, than in patients with mild levels or with psychosocial problems derived from judicial instances. Finally, in the third level of care where the rehabilitation of patients with severe and chronic conditions prevails, the psychologist repeats clinical management of the second level of care and accompanies and guides scientific

practice of the ICD-11 MBNDs. To do

this, it involves a multidisciplinary team in regional and national studies at all levels of care, designs and

evaluates the health care programs

and protocols of the MBNDs taking the ICD-11 as a framework and a comprehensive

and inclusive perspective.

Traditionally, the

psychological approach involves different frameworks to

treat clinical manifestations of a

disorder. For example, from the ICD-11 model,

for a patient with 6C40.2 alcohol dependence, a psychologist using

the psychodynamic framework may

interpret the condition as her attempt to reduce intrapsychic conflict and anxiety through repeated alcohol

use; and that the person when making catharsis and realizing this dynamic can find a corrective

emotional experience. On the other hand, from the behavioral framework, the same professional can interpret the disorder as the patient

learning inadequate habits to

reduce social stress; and the approach

to it is precisely aimed at modifying this learning

through conditioning factors (Hooley et al.,

2021).

As Hooley et al. (2021) stated, from the cognitive- behavioral framework, the

same psychologist can interpret said psychopathology as the irrational thought that the patient

has about his excessive alcohol

consumption as a way to reduce social

stress; and his

approach is based upon guidelines to

modify these irrational thoughts.

Likewise, from a humanistic framework, the psychologist interprets the exaggerated consumption of alcohol

as a blockage or distortion of the natural

growth of the individual

person. In

addition, the psychiatric condition can be overshadowed if the «client» promotes his virtues and achieves

self-realization. Finally, from the existentialist framework, alcohol dependence is

interpreted as a failure for the constructive management of the

«client» in the face of despair and frustration, of his own existence; and that the disorder can be dealt

with by promoting its values,

but also by managing the adverse obstacles

it may encounter.

Evidence-based psychological

interventions for specific diagnostic categories are known to be effective,

but only if they perfectly fit the patient’s

clinical manifestations; situations that are more pragmatic

but unfortunately not very common in clinical

practice (The Psychology Practice, 2021). Thus,

current practice of psychologists, at least in

specialized care, requires

comprehensive management of various psychotherapeutic techniques that have shown evidence for addressing specific symptomatic domains (Livesley, 2018; Tyrer & Mulder, 2022).

This ensures personalized therapeutic attention to individual needs

of the user. This, in turn, generates

greater efficiency within a shorter

intervention time (Tyrer & Mulder, 2022). On the other hand, in primary care where

anxious and depressive disorders

predominate (i. e., with symptoms

that represent common alterations in the somatic and emotional domains),

the progressive approach

with the behavioral

and cognitive- behavioral

approach is more effective and practical. However, for more complex

cases, –such as the

chronic emptiness presented

by a patient with a borderline pattern,

in which alterations in the volitional domain predominate–, it will be necessary to integrate these approaches with others such as the psychodynamic, humanistic, or

existential ones, according to the needs of the patient.

With this, the complexity of multiple domains can be better addressed, which

in ordered sequence are biological, somatic,

emotional, behavioral, cognitive

and volitional ones involved in the patient’s disorders. Certainly, in the domains

closest to biological components, it is simpler to assign a diagnosis and a brief and effective pharmacological and psychological

approach (cure/treatment). However, as

the complexity of the condition progresses owing to the influence

of social and cultural factors,

a complex, comprehensive, and multidisciplinary approach is necessary. In fact, this

perspective of sequential diagnosis

and intervention has been considered for the organization of ICD-11

MBNDs through the lifetime approach;

which, similar to human

development, clearly represents how clinical

manifestations deviate dimensionally (quantitatively) from normality; and they become more

complex as human subjectivity increases with personal experience. From this perspective, the

evaluation and diagnosis with the

ICD-11 must be constant since most

mental disorders by themselves are not chronic;

and they depend a lot on inadequate social functioning

strategies that make the condition last over time, creating and maintaining disability.

(a) Early deprivation or trauma

Since women frequently exhibit more internalizing disorders and males more externalizing and thinking disorders, gender also plays a

significant effect in how mental

problems appear (see Figure 2, for an adequate

identification of these disorders and their equivalence

in the ICD-11). Even though the ICD- 11 does not code gender as a risk factor, it should be considered because it helps identify the diagnosis. For example, a large part of Peruvian women

evidences a higher

suicidal risk (i. e., symptom of 6A70.3 Single episode

depressive disorder, severe, without

psychotic symptoms) and a

large part of the country’s males have a tendency towards aggression (i. e.,

characteristic of 6D11.2 dissociality in

personality disorder or personality difficulty) (Instituto Nacional de Salud Mental, 2019). With this evidence, it could be more certain

to assign a diagnosis of severe depression to Peruvian women and a diagnosis of PD

with prominent

externalizing characteristics to men in the country.

The rejection of immigrants by members

of the new culture of the current

region or nation in which they dwell is known as acculturation, a term frequently employed in the field of mental

health. This social risk factor is

codified in the ICD-11 as QE04 target

of perceived adverse discrimination or persecution. For example, in secular societies

or states, marginalized groups –such as immigrants (WHO, 2021), the gay community (File &

Marlay, 2022), the

Peruvian Andean rural community (Hualparuca-Olivera, 2022; Instituto Nacional

de Salud

Mental, 2019)– can show a greater degree of anxiety and depression due to constant

violence (rejection) they experience.

In addition, it is common to observe

cases in which legal procedures

produce distress, and if such an association is detected, the psychologist can code the current problem as QE40 problem associated with conviction in civil or criminal

proceedings without imprisonment. Often in primary and specialized care,

a Peruvian psychologist is in charge of reporting judicial cases and acts of violence in MINSA records. This serves as epidemiological support

to make decisions on budget management for infrastructure and human resources in the fight against violence and the promotion of a culture of peace. If

these cases are not registered, it is possible

that efforts and investments

would be allocated to other activities in the executive

agenda of the governments.

Although some authors refer that those

adverse factors experienced during infancy and early childhood, including those related

to primary caregivers, are the ones that have the greatest influence on

the onset of a mental disorder, the

truth is that the accumulation (quantity) of social risk factors, more than what they are, contribute to the appearance of mental conditions. Psychologists may decide if a patient’s

diagnosed disorder is accompanied by some social

risk factor or diagnose

only one or more symptoms (e. g.,

MB26.A

suicidal ideation and/or QC4B

personal history of self- harm) rather than diagnosis of a more complex entity

(e. g., 6A71.1 recurrent

depressive disorder, current episode moderate,

without psychotic symptoms)

accompanied by social risk factors

(e. g., QE51 problem associated with interactions with

spouse or partner) if the current

problem is better

explained by social

circumstances, rather than a psychiatric disorder.

In the same way, it is important to

mention that the approach to social risk factors requires multidisciplinary and intersectoral work, the generation

of government regulations and

investments, health promotion

at different levels of care, and the prevention

in primary care. A collaborative work structure is needed between

authorities, health technicians and professionals, educators, among others, to reduce these risk factors.

The way in which a social group experiences each of

the adverse biopsychosocial factors in a certain culture of a region also influences the manifestation of psychopathology (Gureje et al., 2020). The ICD-11 MBNDs working

groups have collected information on cultural variants in order to: (a)

identify cultural concepts of

distress syndrome (causes/explanations, idioms) in various

cultural groups, (b) assess the impact of culture on the manifestation of disorders and their dynamics, (c) identify the differences in the prevalence of various disorders considering the

dynamics and cultural factors

(Sharan & Hans, 2021). The result is mainly

reflected for some of the ICD-11 MBNDs. For example,

6B83 avoidant-restrictive food intake

disorder is diagnosed

mostly in populations of low and middle- income countries (LMICs)

who avoid food intake for fear of generating somatization (Sharan & Hans, 2021; Sharan & Keeley, 2018). Likewise, category 6B04 social

anxiety disorder has a marked

cultural variant in Asian countries (e. g., Japan and South Korea) as

fear of offending others; more than the fear of being evaluated (offended or mocked) socially

(Sharan & Hans, 2021).

An applied example of this variability

in Peru is found in the distress

symptoms of 6B43 Adjustment disorder;

which in Quechua-speaking communities is referred

to as «sunquymi llakisqa kachkan» which can

be translated as «my heart is sad» since the

patient attributes to a part of her body –in this case, her heart– feeling

worried about an adverse situation and not knowing

what to do, which generates

impotence and sadness (Paniagua, 2018; Sharan & Hans, 2021). Spanish-speaking patients, who are native Quechua

speakers, frequently use the term «mi cuerpo hizo razz» to describe

somatic anxiety –as a

Peruvian expression of «ataque de nervios»

(see Paniagua, 2018) in 6B01 panic disorder–

in the form of muscle

contractions that cause the skin to stand on end. Another common attribution in these Spanish- speaking

Peruvian Andean communities (with Quechua

as their mother tongue), –specifically in relatives who attend consultation together with the patient having psychotic symptoms–, is the phrase «su cabeza está débil»

since they think that hearing voices is a product of undernutrition, and consequently

the weakness manifests itself in their head

(as an Andean folkloric explanation of this condition; Quiroz-Valdivia et al., 1997).

In the same way, habits and behaviors

that may appear to be signs of detachment

traits of a personality

disorder (PD) are common behavior in remote

communities of Andean areas whose main economic

activity is mining. In these places, where intense cold is experienced, and with an institutionalized mining economy, –which means that social contact is scarce–, normal behavior can appear to be perceived as a sign of mental

alteration if the psychologist who evaluates them is a foreigner (Hualparuca-Olivera,

2022). Moreover, it is common

for patients to attribute the cause of a mental disorder to witchcraft. This cultural group

certainly does not have sufficient

terms to report a mental disorder and often refers to external

entities to confirm

its possible cause. This leads this community to seek

the service of sorcerers and healers

who recommend them to perform

mystical rituals

instead of seeking

help from mental

health professionals.

Other disorders, in which there is cultural variability in the prevalence and subjective experience of certain symptoms, more than others, are those manifested in: depression,

adjustment disorder. Unlike its previous version

and the DSM-5-TR, in the ICD-11 CDDR it has been decided to eliminate culture-specific diagnostic categories, and sections have been created

to explain possible cultural variations for each disorder (Sharan & Hans, 2021). This change

still generates debate both for the

practice and for the research of the

ICD-11 MBNDs, which mainly argues for two opposing

reasons: (a) the designation of vignettes, instead

of criteria, facilitates the cultural adaptation of diagnostic categories in clinical

practice (Bach et al., 2022); b) the designation of vignettes reflects the lack of interest from the WHO in compiling

exhaustive information on culture

as the priority of scientists is to

find biological markers (Seligman, 2019),

rather than cultural markers in their desire to

universalize the diagnostic system (Sharan & Hans, 2021).

Although the first statement has been continually supported by the ICD-11 MBNDs working group in its research, it is also true that most

of this has been done in high-income countries (HICs). Although they were conducted in LMICs, most of these studies have been conducted in major urban cities,

rather than in remote rural

communities, which represents both a

weakness and an opportunity for the research

and practice of the psychologist and other professionals dedicated

to mental health.

Implications of

ICD-11 MBNDs in public health and its policies

Classification systems have been

criticized for medicalizing common

problems (Stein et al., 2020); however,

the psychopathology subthreshold that is addressed

is relevant for early recognition of future psychiatric disorders –that is, with a focus on primary care (Krasnov, 2021)–.

With the most accurate identification of MBNDs in a country, the availability of assistance services can be evaluated

and plans to implement them can be

structured (Reed, 2021). Furthermore, when combining well-targeted treatment and prevention programs in the field of mental health; and in general,

public strategies, it would be possible to: (a) avoid years lived with disability and deaths, (b) reduce

the stigma associated with mental

disorders, (c) substantially increase social capital, (d) reduce poverty and promote development of a country (Saxena

et al., 2012). When determining what will be financed with a

certain number of resources, the general objective must be to guarantee that health interventions maximize the benefits

for society. For this, evidence-

based prevention programs must be applied to improve positive

mental health (Messias, 2020; Peseschkian

& Remmers, 2020; Sarý & Schlechter, 2020; Smirnova &

Parks, 2018), physical health and

generate economic and social

benefits. In order to favor decision-making in public policies, some issues to be

considered are presented below.

Information systems configure a tool to

improve mental health; however,

difficulties may arise in implementing them due to multiple electronic health records and multiplicity of mental illness classifications.

Many countries have two or more electronic systems

–at least for specialized care units– for registering health information, depending on the state sectors

to which they are attached. An example is the system managed by EsSalud

and the Ministry of Health (MINSA)

in Peru, which are independent

but, in many cases, incompatible.

Another limitation is that there is a group of diagnostic classifications from the WHO and the UN,

to which they must be adjusted as

they offer an international framework for managing, administrating, and researching patients

and services. Making all these classifications compatible allows communication between

healthcare and administrative professionals. It also supports the bases for registering and requesting state

investment for goods and services.

According to Saxena et al. (2012),

ICD-11 MBNDs are mainly linked to four WHO classifications

(in addition to ICD-11 itself) that allow computer management of public health:

(a) the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, (b) the International

Classification of Health Interventions, (c) the International Classification of Primary Care, Third Edition, (d) and the International Classification of External Games of Injury.

In some countries, pilot mapping

studies between clinical

terminologies are being carried out, considering

three layers : (i) Foundation –i. e., a

semantic network of biomedical concepts;

e. g., Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms (SNOMED-CT) and the ICD-11

Foundation Component–, (ii) a formal coding that anchors the meaning

of terms in the semantic web, (iii) Linearization –i. e., a classical tabulation of hierarchical codes that are derived from that network—,

and (iv) Content Model —i. e., an information model of mandatory and optional content, to which each entry in the semantic

network is associated– (Chute & Çelik, 2022).

In the USA, for example, there are

consulting firms Kathy Giannangelo Consulting, LLC and the RXNT compatible software designer corporation, who support the implementation of the ICD-11 clinical codes

to facilitate the billing and reimbursement processes for benefits and medications (e. g., psychotropic

drugs), in addition to training health servers on the classifications of the WHO. However, implementation in developing countries

will require significant effort and

investment (Almeida et al., 2020).

The implementation experiences of the ICD- 11

in countries like Iran (Golpira et al., 2021) and Kuwait

(Ibrahim et al., 2022) can serve as a reference

for other HICs and LMICs in the Latin American

region.

Another aspect to be considered is that

mental health activities in Peru have been usually coded based on health information systems (HIS).

Based on a normative guide (Ministerio de Salud, 2021),

packages are established

(which include the type and quantity of activities) for care and follow-up according to the user’s diagnosis at the different levels

of care. As Hualparuca-Olivera (2022) mentions,

these packages have been prioritized for anxiety, depression, psychosis, and substance use disorders; fact that has limited the clinical management and research of these and other psychopathological

conditions. Moreover, with this

strict rule, diagnosis has often become a sociopolitical consensus to meet health goals (Hualparuca-Olivera, 2022). Although this makes it possible to quantitatively organize the activities and the health budget, it becomes a tedious and unnecessary task for the

healthcare personnel since it fails

to provide quality care and effective

treatment to the user. In this sense, the flexibility offered

by the diagnostic guidelines of the ICD-11 MBNDs to prioritize the

clinician’s criteria could be subtly

transferred to current regulations to improve

the clinical use of the mental health activities proposed

by MINSA.

With the arrival of ICD-11, it is

expected that governments, in coordination with the WHO, or with

its regional entities such as the Pan American Health

Organization, academic societies,

non-governmental organizations would create bridges of communication with

state leaders to establish strategies in order to train each health professionals, administrators and managers on the use of the ICD-11 (Krasnov, 2021; Stein et al., 2020). Likewise, state leaders and their

ministers should organize working

groups to adapt ICD-11 to local laws, policies, health systems and infrastructures, and subsequently design various multilevel actions and train mental health practitioners (Fiorillo & Falkai, 2021). Although educational resources are

available online, the implementation

and training of health professionals (by the Peruvian authorities) has not yet started; and it will take time (R. Valle [Psychiatrist of the National Institute of Mental Health

‘Honorio Delgado-Hideyo

Noguchi’], personal communication, December

1, 2022). Even epidemiological studies

on mental health

in the country are being carried out under the ICD-10 framework. Everything suggests that the implementation of the ICD-11 in Peru will

begin, at least, in a future

five-year period.

Furthermore, since the education of health professionals

represents one of the most essential steps to implement and disseminate the new classification system in routine

care, the WHO International

Advisory Group led by Geoffrey M. Reed has organized

training courses for professionals on the use of the ICD-11 MBNDs chapter

through the GCP Network platform. Likewise,

psychiatric associations, mainly

centralized in Europe and the USA,

have provided educational activities through

interactive virtual formats, including online courses with the active participation of students

through the application of the new guidelines

to clinical cases and discussion of diagnostic dilemmas

(Reed, 2021). Certainly, these trainings

have focused on psychiatrists and at the moment have left aside

other mental health

professionals or those who work on mental health

issues.

Because

ICD-11 will represent

an important change in global clinical practice, it is urgent to promote educational activities to improve the dissemination of this innovative classification approach and contribute to the continuing education of mental

health and related professionals. Also, The WHO Collaborating Centre voor de Familie van Internationale Classificaties in Nederland (WHO-FIC Netwerk; 2019) established a roadmap for the Americas that can be adapted for mental

health issues when implementing ICD-11.

The promotion and dissemination stage, for example, mainly involves (a) designing and strengthening committees, councils

or inter-institutional health

information centers (health

statistics, social security and civil registration);

(b) developing a transition plan and implementation of ICD-10 to ICD-11 aligned

with the country’s health information improvement plan; and (c) develop attractive materials in different formats and use social networks to spread ICD-11 innovations (Fiorillo & Falkai, 2021).

In primary health care (PHC), a large

number of new patients have to be

treated, and certainly the official

version of ICD-11 is not practical. For this

reason, the WHO interested in mental health is in the process of revising the Diagnostic and

Management Guidelines for Mental Disorders in Primary Care 11th revision (ICD-11

PHC). The previous

version (ICD- 10 PHC) included 26 common mental

disorders or relevant to these settings.

The ICD-11 PHC describes

27 mental disorders, 25 of which are equivalent to the ICD-11

MBNDs (Chapman, 2019);

and include problems

with drugs, alcohol,

eating and sleeping, and the body stress syndrome (BSS; see Regier et al., 2020; Robles-García & Reed, 2017). Also, in the ICD-11 PHC, common

presentations in primary care,

distinctive characteristics and relevant differential diagnoses are described; and information for the patient and family, response to both psychological and pharmacological treatment

and indications for referral to a

specialist (Regier et al., 2020). Revisions have also been proposed for mood

and anxiety disorders, BSS, and health anxiety

(HA) proposed for the ICD-11

PHC and suggested that these

categories could be usefully implemented in global primary

care settings (Goldberg et al., 2017).

In PHC, it is important to recognize and intervene in the depressive symptoms that commonly accompany

chronic physical disorders

and the management of multiple somatic symptoms without any accompanying physical illness. According to some authors refer, it is recognized in the ICD-11 PHC that depression

and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) commonly co-exist, but the diagnostic requirements for depression include a duration of only 2 weeks, while

the requirement for GAD is several months (Razzaque & Minhas, 2018) since the most frequent thing is that a patient

develops anxiety due to his own depressive state condition. This has implications for early management;

since the previous condition

(depression) can be intervened in the first two weeks before

anxiety is generated. Otherwise, a combination of both conditions in clinical thresholds (depression-anxiety) probably leads to comorbidity with other mental

disorders or possible suicide (Regier et al., 2020).

Mixed

states of anxiety

and depressive symptoms

(«cothymia»; see Yang et al., 2022) with

subclinical thresholds are very

common in community settings. For this reason, the WHO Primary

Care Consultative Group recommends three main ways of diagnosis: (a) if there is depressive disorder

(clinical level or

«disorder») + anxiety

disorder (clinical level),

then it is diagnosed as «anxious depression»;

(b) if there is depressive disorder (clinical level) + anxiety disorder

(subclinical level), then it is diagnosed as «depression with current anxiety»; and (c) if there

is depressive disorder (subclinical level) + anxiety

disorder (subclinical level), then it is diagnosed as «subclinical anxious

depression» (see Regier et al., 2020).

Likewise, the ICD-11 Primary

Care Consultation Group evaluated two brief anxiety and

depression screening scales based on

an assembly of the items from the Composite

International Diagnostic Interview

adapted for primary care (CIDI-PC) to help primary care mental health professionals to decide whether

a diagnosable psychological problem was likely to be present (Goldberg et al., 2012). Given

the time and resource pressures –in

addition to patients’ reading comprehension issues– these screening

scales will be especially

useful in LMICs and will be published alongside the ICD-11 PHC (Warren, 2017). The application of these

scales will be soon implemented in all primary care health centers and in mental health care

units within educational institutions

where mental health personnel

work (e. g., school psychologists financed by regional governments) for early detection of negative emotional symptoms. In

addition, it is likely that these

professionals need training in brief cognitive

behavioral interventions to intervene in these cases.

Health

policies for primary

care should also focus on improving the population’s access to mental health services. The need to increase budget for investment in hiring more and better qualified mental health professionals

has been alerted in addition to

improving and increasing primary care services

to achieve better coverage (WHO, 2022a).

Unfortunately, in many LMICs,

specialized care is overwhelmed, and primary

care is very helpful in assisting to ease the

demand for mental health services (Kyanko et

al., 2022; WHO, 2022a). The

importance of improving working

conditions of health professionals for their

own mental well-being in a post-pandemic context has also been highlighted; which also affects

the quality of care in the mental

health services that they offer (Belloni et al., 2022; Shields et al., 2021; WHO, 2022f). The implementation of the ICD-11

MBNDs in primary care should

also consider all these issues.

Mental

disorders are strongly

associated with disability, a term that includes dysfunction of the brain, the body, in your personal

daily activities, and restrictions in your social life. Both physical illnesses and mental disorders have an influence (as a sufficient

or contributing cause) in the disability generation. Disability is often a key factor in:

(a) people seeking

health care; and an important factor in (b) health providers

determining the types of health services

and level of care needed.

However, the frequency, etiology (type of causality), and manifestation of disabilities generated by mental disorders are not well defined

or scientifically studied

(Regier et al., 2020). An attempt has been made to keep

disability out of the main diagnostic

classification of the ICD-11 since it has only incorporated a supplementary

section called the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). This section

has a disability measurement instrument, WHODAS 2.0, which includes

the following domains: (1) understanding and communication with the

world (cognition); (2) movement and

move (mobility); (3) self-care; (4)

get along with people (interpersonal relationships); (5) home life, occupation, school,

and leisure; and (6) participation in society.

The ICD-11 –like the DSM-5-TR–

has a tradition of incorporating part of the disability construct

for all its disorders, which it names

as «impairment»; which

primarily focuses on social dysfunction. Impairment for each

of the disorders is also accompanied by subjective

«distress»; and for mental disorders that are

dimensionally classified in ICD-11, they define their «severity» (i. e., mild, moderate, or severe). This is where the question arises, why is social dysfunction included in mental disorders

as part of the diagnostic guidelines, unlike the other physical illnesses of the ICD-11? This has to do with scientific and

practical issues since, unlike physical

illnesses, it is very difficult to detect a single (or at least

generalizable) etiology for mental

disorders. Using the guidelines alone, without

including distress or impairment in mental disorders, was shown to lead to high rates of disorder

prevalence; this, without

people generating any personal

or social dysfunction (Regier et al., 2020). Consequently,

it was decided that these two

indicators (distress

and social impairment) constitute the clinical importance of the ICD-11 MBNDs.

According to Saxena et al. (2012), social insurance (financed by state and/or private entities) mainly covers the payment of health services,

distribution of medicines and health devices for a particular patient who pays a monthly

payment. In the event that the

patient cannot pay, a validated disability

certificate is needed so that the insurance continues to be maintained and they continue

to receive decent care. For a

long time in HIC social insurance, the DSM criterion

has been used to regulate

disability criteria, which mainly include:

(a) the existence of a