https://doi.org/10.24265/liberabit.2022.v28n2.617

ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN

Social Representations of COVID-19 Among Brazilian

Elderly Women: A Structural Approach

Representaciones sociales de la COVID-19 entre mujeres mayores brasileñas: una aproximación estructural

Alda Vanessa Cardoso Ferreiraa,*

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8010-3234

Ludgleydson Fernandes de Araújoa

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4486-7565

Raimundo Nonato de Sousa Barros Netoa

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5066-142X

aUniversidade Federal do Delta do Parnaíba, Brazil

Autor

corresponsal

aldavanessacafer@gmail.com

Para citar este artículo:

Cardoso, A. V., Fernandes, L., & Barros,

R. (2022). Social Representations of COVID-19 Among Brazilian Elderly

Women: A Structural Approach. Liberabit, 28(2), e617. https://doi.org/ 10.24265/liberabit.2022.v28n2.617

Abstract

Background:

In January 2020, the World Health Organization

declared the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) «a public health emergency of international concern»

owing to the detection

of cases and the rapid spread of the disease.

Objective: This study aimed at understanding the

social representations of COVID-19 among

Brazilian elderly women. Method: A

total of 100 elderly women

selected by convenience sampling, with an average

age of 69.24 years old (SD = 6.58),

participated in the study. Data were

collected online using a sociodemographic questionnaire

and a free word association test (FWAT) with the stimulus word «COVID-19.» The

responses were examined by prototypical

analysis through IRaMuTeQ. Results: The social representations

of COVID-19 emphasize death and fear of the disease

caused by the novel coronavirus. Elements associated with measures to contain the virus are also part of the representational field. Conclusions: Understanding social representations of COVID-19 in elderly

women may contribute to short- and long-term interventions to reduce the psychosocial consequences of COVID-19

in this age group.

Keywords: social

representations, structural approach, COVID- 19, pandemic, elderly women.

Resumen

Antecedentes: en enero de 2020, la Organización

Mundial de la Salud

declaró a la enfermedad por coronavirus 2019(COVID- 19) «una emergencia de salud pública de importancia internacional» como resultado de la detección del número de casos y la rápida expansión de la enfermedad. Objetivo: este estudio tuvo como objetivo

comprender las representaciones sociales de mujeres mayores brasileñas sobre la COVID-19. Método: participaron un total de

100 mujeres adultas mayores, seleccionadas por conveniencia y que tenían en promedio 69.24

años (DE

= 6.58). La recolección de datos

se realizó en línea mediante un cuestionario sociodemográfico y un test de asociación libre de palabras

(TALP) con la palabra estímulo

«COVID-19». Las respuestas al

TALP se examinaron mediante un análisis prototípico utilizando el programa IRaMuTeQ. Resultados: las representaciones sociales de la COVID-19

enfatizan la muerte y el miedo a la enfermedad provocada por el nuevo coronavirus. Elementos

asociados con las medidas

de contención del virus también forman parte del campo representacional. Conclusiones: comprender las representaciones sociales de la

COVID-19 en mujeres mayores puede contribuir con intervenciones

a corto y largo plazo que minimicen las repercusiones psicosociales causadas por la COVID-19 en este grupo poblacional.

Palabras clave: representaciones sociales; abordaje estructural; COVID-19; pandemia; mujeres adultas mayores.

Introduction

In December 2019,

a novel coronavirus appeared in China:

SARS-CoV-2, a virus responsible for an outbreak

reported for the first time in the city of Wuhan.

This virus has rapidly spread around the world by travelers and the number of cases worldwide

has surpassed 72 million, with more than one million deaths by December 14, 2020 (Worldometer, n.d.).

However, the numbers

reported are underestimated,

considering that infected asymptomatic individuals might not have been tested, and that standardized protocols and notification methods have been critically lacking

in several countries

(Oran & Topol, 2020).

On January 23, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared «a public health emergency

of international concern» owing to the detection

of cases in various Asian countries and highlighting

the rapid spread of the disease. The pandemic

caused significant impacts on the elderly population,

such as increased symptoms of anxiety and depression, increased loneliness, less socialization, decreased practice of physical activities, job loss, worsening of health status since the onset

of the pandemic: a condition most

reported among women (Novais et al., 2021).

A review study conducted by Pereira et al. (2022)

on the real or potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of the elderly highlighted the occurrence of anxiety,

depression, loneliness, stress,

feeling of fear or panic, sadness, suicide

or suicidal ideation and insomnia. In studies

conducted by Wegner et al. (2021), social isolation and other strategies to minimize the

transmission of COVID-19 had impacts

on the physical activity of women, who reported decreased

levels of these activities and concern about the pandemic

reality.

A phenomenon that accompanies population aging is the feminization of old

age, in which there is a higher

proportion of women than men in the elderly

population, especially at older ages (Sousa et al.,

2018). The process of feminization of old age can be experienced

in a discriminatory way due to gender and

age. On the other hand, the feminization of old age is not limited to the fact that there are more elderly women in Brazil and that they live longer than men, but it includes social-historical

contexts that make Brazilian women

more likely to be vulnerable to inequality, disasters’ impacts, and overall survival than men (Cepellos, 2021; Okai, 2022).

In the pandemic

scenario, women are more susceptible to the risk of contamination

and to the social vulnerabilities that stem from that reality,

such as unemployment,

violence, lack of access to health services

and increase of poverty (Canavêz et al., 2021). Santana et al. (2022) highlights

that the main elements that contributed to the increased vulnerability of women to violence in the context

of the pandemic were ethnicity

(mainly black women), partial

closure of complaint

services, low schooling, economic dependence, among others.

Social distancing measures, such as suspension of events, cancellation of classes, quarantine of the population and risk groups, restriction

on the use of public transport (Da

Silva et al., 2021) and use of masks

(De Sousa et al., 2021), were adopted in the

Brazilian context to minimize the transmission of the virus. Studies have shown that elderly with comorbidities

were three times more likely to agree with the preventive measures

adopted for social distancing than those without comorbidities (Filho et al., 2021). Romero et al. (2021) identified that adherence

to total social distancing was higher among elderly

women.

The psychosocial, emotional, and behavioral implications of the pandemic in the elderly population may be related to social isolation, fear

of contagion, feelings of abandonment, loneliness, sadness, fear of death, panic, emotional lability, sleep disorders, loss of

appetite, among others (Faria & Patiño, 2022). A study

conducted with Brazilians showed that the genesis of the social

representations of the novel

coronavirus is marked by concerns

related to its dissemination,

psychosocial implications (collective concern about the prevention of COVID-19 and prophylactic

care) and affective issues (uncertainty, feelings

of fear and despair) (Do Bú et al., 2020). Studies developed by Joia et al. (2022) pointed

out that politics and government, social distancing, death, and fear made up the central

number of social representations of the pandemic among the Brazilians.

Thus,

knowing the social representations of COVID-19

among elderly people can help understand the feelings aroused, what preventive

measures they consider to be

relevant and how they interpret the reality experienced (Oliveira et al., 2020). Given this context,

it is important to research

the social representations of COVID-19 among elderly women, mainly considering that the virus propagation not only affected the number of dead and infected

people but also has psychosocial implications. Social representations are understood as a set of

values, ideas epresses

that establish an order which guides people

in their material and social world, besides allowing

the communication among the members of a community (Moscovici, 2007).

Seeking

to explain the social representations’ genesis, Moscovici

developed two important concepts: anchoring and objectification.

Anchoring can be understood as the process

of incorporation and assimilation of a new object to a set of categories that are familiar

to the individuals and are easily available

in the memory, allowing the integration of that object

of representation to a set of proper values in a way that individuals start to name and classify it from their social

insertion (Almeida & Santos, 2011; Bertoni & Galinkin,

2017). In objectivation, the new object is integrated to the structures of the daily action: what is abstract becomes concrete (Jodelet, 2018).

The structural approach

proposes that social epressentation is organized around a central nucleus characterized by stability, resistance to change, translation of meaning; moreover,

it is related to collective

memory and peripheral elements, which allow

adaptation to reality and capture singularities from individualized experiences (De Melo et al., 2020; Parreira et al., 2018). The core

elements, therefore, are characterized as more abstract, stable and with a more normative nature,

while the peripheral elements are characterized

as more concrete, unstable, and more related to particular

situations (Flament, 2001). Given the aforementioned this study aims mainly at understanding the social representations of COVID-19 among Brazilian elderly women.

Method

Type of research

This

is a qualitative, exploratory, descriptive, and cross-sectional study.

Participants

The sample included

100 elderly women from 13 Brazilian

states, more specifically, Piauí (41%), Rio de Janeiro (22%),

Ceará (18%), Maranhão (5%),

São Paulo (4%), Pernambuco (4%), Rio Grande do Norte (1%),

Distrito Federal (1%), Espírito Santo (1%), Goiás (1%), Paraíba (1%) and Rio Grande do Sul (1%). The participants’ ages varied from 60 to 83 years old (M = 69.24, SD =

6.58). Most of them were

married (39%) and

had a secondary level of education

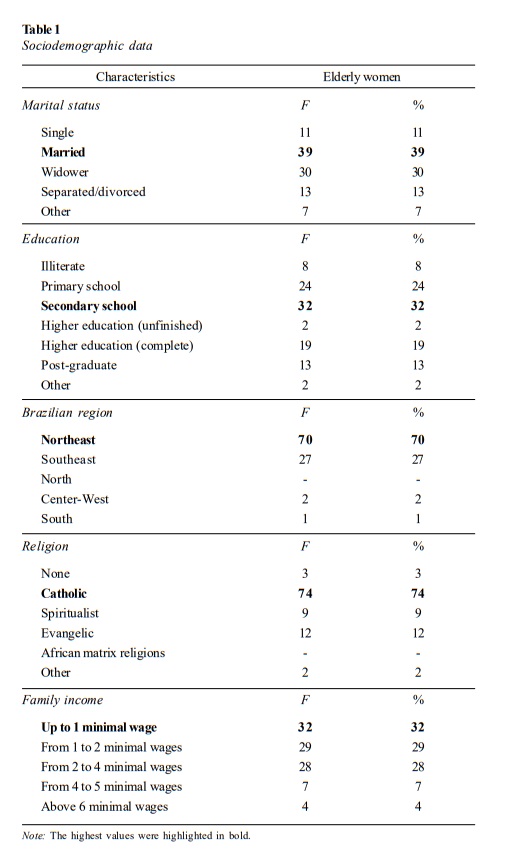

(32%) (see Table 1).

The following criteria

were considered for selecting

the sample: 1) being 60 years old or older,

2) not having any disorder

that could hamper communication, 3) agreeing to participate in the study freely and voluntarily. Also, 1) being

Brazilian, 2) being a female, 3) having access to the Internet.

Measures

Two instruments were used to collect the

data: a sociodemographic questionnaire and a free word association test (FWAT).

Sociodemographic questionnaire. This questionnaire was used to characterize the sample and to collect the participants’ sociodemographic information such as their age, their skin color, their sexual

orientation, the Brazilian state

where they lived, their marital status,

if they developed a paid activity, if they were retired

and/or a pensioner, their income, if they were the main responsible for the family’s

financial support, if they received aids from government programs, their religiosity, their education, the number of children they had, if they did any physical and leisure activity, if they were diagnosed with COVID-19, and if they were hospitalized.

Free word association test

(FWAT). A

FWAT was used to collect the social

representations of the participants (Neves et al., 2014). To accomplish that, the stimulus

word «COVID-19» was used, for which five

evocations were requested. A FWAT allows

the identification of semantic universes

with the evocation of

responses to a stimuli word –or words– and is

widely used in studies based on the theory of social representations (Coutinho, 2017; Mota et al., 2018).

Procedure

This study is part of an «umbrella» project called Qualidade de vida e atitudes frente a pandemia da COVID-19: Um estudo

transcultural entre idosos (in English, Quality

of Life and Attitudes Towards the COVID-19

Pandemic: A Transcultural Study Among Elderly

People), which was submitted to the Research

Ethics Committee (CEP) of the Federal University of Parnaíba Delta and approved on August 30, 2021, according to the opinion

document number 4.092.097 and CAEE 478831121.5.0000.5214. After

the approval from CEP, the recruitment of participants

started –by means of social networks (Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp) and by accessing telephone contacts through groups and institutions that provide assistance to elderly women– after proper

authorization was granted.

Data were collected

from October 2021 to May 2022.

If inclusion criteria

were met, women were invited to participate, and the purpose of

the study was explained. Afterwards, a Google Forms link was sent

so they could fill it in. The form used was self- administered. The consent form, study aims, instructions and

measurements were included. By reading and accepting the consent form, the participants declared being aware of the

study risks and benefits, as well as

their right to withdraw from the

study at any time. To respond to any difficulties when filling out or handling

the form, the researchers informed the participants that they were

available to assist them in such a

task. After confirming their participation,

a day and time were scheduled for the participants to fill the study form with online support (video call) on WhatsApp. After that, it

was the researcher who completed the

form based on the participants’

responses. When possible, video calls with

the participants’ consent were recorded. The

confidentiality and the privacy of the information were assured,

and all the material obtained

was stored in a safe place.

Data analysis

A descriptive statistical analysis of the sociodemographic

information was conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics version

25 to identify the averages, standard deviations, and

percentages. The data obtained

from FWAT were tabulated on a spreadsheet using OpenOffice

software and organized according to the participants’

order of evocation. Afterwards, the spreadsheet was imported

to IraMuTeQ (Interface de R pour les

Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de

Questionnaires) version

.7 alpha. In this software, the matrix analyses, more specifically, the multiple frequency analysis and the

prototypical analysis were carried out. According to Verges

(1992), the latter is also called «evocation

analysis» or «four-house square», one of the most frequently used techniques to explore the structure of social representations, which is based on the calculation

of frequencies and average order of the words’ evocations.

The semantic criterion was adopted to

group the answers, i.e., the evocations

were classified according to meaning similarity. The minimum frequency

considered for the inclusion of words in the quadrants was three, which was equivalent to 3% of the sample

size. Regarding the delimitation of the cut points for the quadrant’s coordinates, the

evocation rank order was employed

(Wachelke & Wolter,

2011).

In this

sense, the data obtained from the prototypical analysis were understood from the structural approach (Abric,

2003), which conceives social

representations as a structure with a central

core and a peripheral one. It is also worth

mentioning that the study, including

its measures and the participants’

responses, was carried out in Brazilian Portuguese.

When the study report was finished, it was translated into English.

Results

Table 1 contains

the detailed description of the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics.

Out of all the participants, 44% declared themselves

being swarthy. Most of them were from Piauí state (where the study originated); 41% still held a paid activity (15% - formal jobs, 26%

- informal jobs); 86% was retired

and/or received a pension, 49% was

the main responsible for their family’s financial support,

and 90% declared not having received

any aid from governmental programs. In relation to the dwelling, 39% of the participants lived with

a companion or with a spouse. A total of 81%

and 74% did some type of physical

and leisure activity,

respectively. Only 39% was diagnosed

with COVID-19, out of whom

only 5% was hospitalized. Regarding

the losses for COVID-19, 34% of the participants reported having lost someone they loved (friends, relatives, and neighbors).

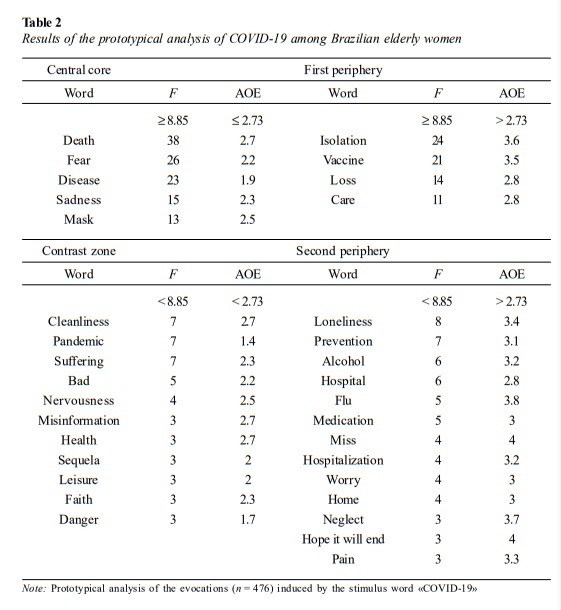

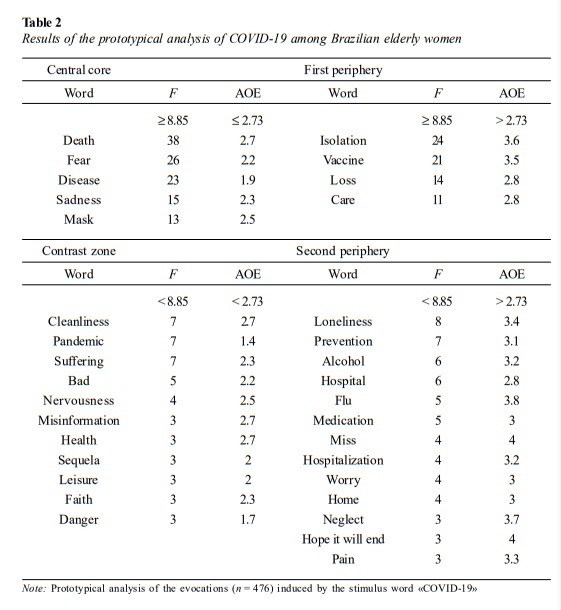

The prototypical

analysis is the organization of the answers based on the

frequency (F) and the average order of evocation (AOE) or average

position at which the answer appears among the answers evoked (Wachelke et al., 2016). A total

of 476 evocations to the stimulus word «COVID-19» could be identified, considering the omitted

cases. Therefore, the words with AOE below 2.73 were classified as having low evocation order

(see Table 2). The results of the

prototypical analysis about COVID-19 are shown in Table 2.

Table

2 left upper part presents

the categories that

compose the first quadrant, which corresponds to the core elements or the central core of the representation. The first quadrant

is composed of the words with high frequency (F) and low

AOE, i.e., words promptly evoked

after the presentation of the stimulus word and used by a great number of participants. The first quadrant

of Table 2, where the central core is, consisted of recurring evocations (ƒ 8.85) with high hierarchy (AOE 2.73), where the expressions «death», «fear», «disease»,

«sadness», and «mask» are highlighted as core elements

of the social representations of COVID-19. Those

elements represent what was more consensual among

the participants and, therefore, more strongly shared among them.

Older

adults, particularly women, have been affected by a higher risk of serious health complications that may result in various

mental- related problems, such as

anxiety and depression symptoms,

sleep disorders or other disorders (Khalaf

et al., 2022). In the COVID-19 pandemic,

the fear of COVID-19 was significantly higher in

women compared to men and in

individuals with chronic diseases compared

to those without

any chronic disease

(Bakioglu et al., 2021).

The first periphery, located on the

right upper quadrant (see Table 2),

contains the high-frequency words

with a high order of evocation. It means that

AOE was higher than the core elements: although the words

had a high frequency of evocation, they were

not promptly evoked –like the words that are part of the central core– besides being above the AOE cut

Discussion

The results from the prototypical

analysis of the responses to the

stimulus word «COVID-19» allow identifying

the elements that compose the structure of its social representation. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the impact that emerging infectious diseases have on becoming a Public Health Emergency of International Concern

(Assefa et al., 2022). One year after the first appearance of a COVID-19 case, Brazil was considered the

second country in number of deaths worldwide; besides

that, individuals aged 60 to 69 years

accounted for 45,467

(46.4%) deaths, out of which 17,950 were women (46.8%) (Castro et al., 2020).

The results obtained

in this study evidence one of the COVID-19 pandemic impacts: the large

number of deaths because of the

disease and complications associated

with it. This impact had been reported in other

studies (França et al., 2020; Mascarello

et al., 2021; Pereira et al., 2022).

Among the reasons why COVID-19 is

considered a threat, the possibility of high-income

elderly people and even healthy adults to die is highlighted (Campiolo et al., 2020).

Erbesler

and Demir (2022) identified that death was pointed

out as the biggest fear among the elderly people who had been diagnosed with

COVID-19. The fact that COVID-19

is an infectious disease, high mortality rates, uncertainties about the

future and classification of the

elderly as part of the risk group can

cause these people to think about death, raising the levels of anxiety and depression.

Fear, evoked by the participants of this study, may be associated with the fear

of being infected with COVID-19; it

can serve as an adaptive emotion in that

it helps the individual to deal with a potential threat but, if it is not properly

proportional to the real threat,

it can be unadaptive (Rubio et al., 2022).

The pandemic acted as a prolonged psychosocial stressor that may have affected

personal adaptive coping

resources (Friesen et al., 2022).

It is important to note that, in a study

conducted by Passos and Araújo (2021) with lecturers

of Brazilian private

higher education institutions on the social representations of COVID-19, the expressions

«death», «disease», «fear», and «mask» were also the elements that composed the core zone. As a result, it can be inferred that, although the

two groups are different, the

consonance between them may reveal the macrosocial context and the humanitarian/sanitary crisis constructed from the intergroup relationship with the physical and social environment in which they live (De Sousa & De Souza, 2021).

Complementing the core zone, the words promptly evoked on the contrasting zone were «suffering»,

«bad», and «nervousness». These might indicate the psychosocial

negative consequences stemming from the

deaths caused by COVID-19. These results are

consistent with findings,

in the pandemic context, of feelings of loneliness, fear and anxiety,

together with the fear by the high rates of viral transmission (Bezerra, Saintrain, et al., 2020; Islam et al., 2020; Lin, 2020).

Disaster situations and major emergencies can be disorganizing

and have great potential for physical

and psychic illnesses for

people directly or indirectly affected,

so that mental health becomes an easy target (Rafaloski et al., 2020). Nevertheless, not all demands of psychological order can be classified as a disorder;

they can be normal and expected reactions in face of an unusual

and unexpected situation. In addition, the effects

on mental health can have more consequences among low-income populations who live in precarious situations, with limited access to health

and social assistance (Assefa et al.,

2022; Fundação Oswaldo Cruz [FIOCRUZ], 2020; Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde [OPAS], 2009).

Concerning the elements evoked in the first periphery, the following aspects

were identified: protective and preventive measures

against the virus,

and the impacts caused by COVID-19, expressed in terms like «loss»,

from which concrete

and symbolic losses can be inferred. «Isolation» and «care», evoked

by the participants, denote measures that were efficient to reduce the transmission of

the virus and even prevent the

collapse of the hospital system (Da Silva et al., 2021).

Social

isolation during the pandemic changed

people’s daily lives and was associated with a significant increase of unemployment, sleep and stress alterations, and challenges to the practice

of physical activities (Bezerra, Silva,

et al., 2020). Among elderly people,

social isolation represented an increased risk of cardiovascular

and autoimmune problems, neurocognitive and mental health issues,

besides the fact that the social

disconnection may increase the risks of depression and anxiety (Armitage & Nellums, 2020), distancing

from family and social networks, feelings

of loneliness, prevention of free circulation,

damage to the autonomy, interruption of work and physical activities, lack of medical assistance for preexisting diseases, and other diagnoses

(Casselato et

al., 2020). At the end, this last sentence neither provides any information regarding the study results nor is the main theme of the cited reference.

The massive losses caused by the COVID-19

pandemic had psychosocial consequences (Carvalho et al., 2021). In many situations, it

was not possible to say goodbye to the beloved

ones who died (Giamattey et al., 2022; Pauli et al., 2022; Yildiz et al., 2022). On the other hand, the losses,

in the COVID-19 scenario, are experimented in multiple forms: loss of the normal life, loss of

jobs or loss of physical

intimacy (Ramadas & Vijayakumar, 2021).

The term «vaccine», evoked by the

participants at the first periphery, may reflect the Brazilian context in relation to the immunization process when the data were collected. With the

beginning of the vaccination in the first months of 2021, the age profile of the serious cases and deaths changed,

reducing the impact of the disease,

deaths, and severe cases. In June 2021, although

serious cases concentrated in more advanced

ages, there was a significant reduction of the age average of those cases and deaths,

a period that coincided with a great vaccine coverage of the elderly

population (FIOCRUZ, 2021a,

2021b; Kabad

& Souto, 2022).

The vaccination against COVID-19 can

reduce mortality rates and is a strategy

to protect the elderly population’s health (Souto & Kabad, 2020) and control

the pandemic (Pagno, 2021).

Concerning the adhesion of Brazilian seniors to the vaccination, some studies

pointed out that 92.4% of elderly women had been or had the intention

to be vaccinated. The factor

most strongly associated to the intention of getting vaccinated was the source of information.

Those people who had information about immunizers from

the Brazilian Ministry of Health, or from the traditional media, were more prone to get the

vaccines than those who had information from friends and from the social

media networks as their source of knowledge

(Lima-Costa et al., 2022).

Final

remarks

The present study aimed at identifying

the social representations of COVID-19 among

Brazilian elderly women. It was possible

to identify that those representations

are strongly associated to death and to the fear that the disease

imposes on society.

Notwithstanding, the elderly population was one of the groups that suffered the most with the consequences of COVID-19 and because of the impact caused by the social isolation measures,

although they were necessary to reduce the virus transmission.

In general, the peripheral elements do

not differ from the core elements.

The study participants recognized the protection and virus-containment measures

–such as isolation, vaccine, and care– without

forgetting the feelings that the pandemic caused them, evoked from the terms «suffering»,

«bad» and «nervousness», and evidenced in the peripheral

social representations. The feeling of threat may lead to the necessity of

protection and movement; nevertheless, when people have intensively lived for

a

long time, they can have psychosocial and emotional consequences, which denote

the need for a careful vision. This

situation considers the specificities of elderly

women, as well as the social vulnerability to

which they are submitted.

Among the study strengths, we can

mention the following: the target

public; the study of a problem within

the pandemic context, where there is still a

scenario of uncertainty, many questions, and some answers; and the online data collection, which allowed conducting the research in states

different from the one where the

study originated. On the other hand, the

online data collection was a limitation as elderly women who do not have access to the Internet did not meet the inclusion criteria of the study. Moreover, the research did not

cover states in northern Brazil.

Finally, with the analysis

carried out and the conceptions learned, it is expected that

this study contribute to governmental

and non-governmental strategies for reducing the psychosocial consequences caused

by COVID-19, such as the provision of emotional

and social support and public policies which consider the special characteristics of the study group and how these social representations

about COVID- 19 guide experiences, decision-making and behaviors during the pandemic reality. Therefore,

considering these aspects can help the construction and dissemination of representations and social practices that continue to control COVID-19 in the Brazilian context.

Moreover, new studies about this topic

which include elderly women from

states not represented in this study, mainly from the north region,

are necessary. Furthermore,

it is recommended to conduct longitudinal studies on social

representations that can

monitor and deepen the evolution of the perception

of the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to

including elderly women who do not have access

to the Internet.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that this study was

carried out without any commercial or financial relation

that could be interpreted as a potential

conflict of interest.

Ethical responsibility

The data were collected in a way to

ensure the participants’ privacy and

anonymity. Therefore, the project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee

of Federal University of Piaui; number

4.092.097. The participants received a free and informed consent form which explained the

study, risks of participation, as well as guaranteed the confidentiality

and security of data collection. The data gathering

began after the signature of the consent

form.

Authorship contribution

AVCF:

study design, data processing

and interpretation, introduction, body of the review, conclusions, general review and writing in APA format.

LFA: design of the study, interpretation of the data, introduction, body of the review, conclusions, general review,

and writing

in

APA format.

RNSBN:

design of the study, interpretation of the data, introduction, body of the review,

conclusions, general review, and writing in APA format.

References

Abric, J. C. (2003). Abordagem Estrutural das Representações Sociais: Desenvolvimentos Recentes. In P. H. F. Campos & M. C. S. Loureiro (Eds.),

Representações sociais e práticas educativas (pp. 37- 57). Editora da UCG.

Almeida, A. M. O., & Santos, M. F. S. (2011). A teoria

das representações sociais. In C. V. T. Torres & E. R. Neiva (Eds.), Psicologia social:

Principais

temas e vertentes (pp. 282-295). Artmed.

Araújo, L. G. L. & Eichler, M. L.

(2022). O descaso epistêmico diante da pandemia de COVID-19 no Brasil. Thema, 21(1), 174-189.

https://doi.org/10.15536/thema.V21.2022.174-189.2184

Armitage, R., & Nellums L. B. (2020).

COVID-19 and the Consequences

of Isolating the Elderly. The Lancet. Public Health, 5(5), Article

e256. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X

Assefa, Y., Gilks, C. F., Reid, S., Van de Pas, R., Gete, D. G., &

Van Damme, W. (2022). Analysis of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons Towards a More Effective Response

to Public Health Emergencies. Global Health, 18(10), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-022-00805-9

Bakioglu,

F., Korkmaz, O., & Ercan, H. (2021). Fear of COVID-19

and Positivity: Mediating Role of

Intolerance of Uncertainty, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19, 2369-2382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00331-y

Bertoni,

L. M., & Galinkin, A. L. (2017). Teoria e métodos em

representações sociais. In

L. P. Mororó, M. E. S. Couto, & R. A. M. Assis (Eds.),

Notas teórico- metodológicas de pesquisas em educação: Concepções e trajetórias (pp. 101-122). EDITUS.

Bezerra, A. C. V., Silva, C. E. M., Soares, F. R. G., & Silva, J.

A.

M. (2020). Fatores associados ao

comportamento da população durante o isolamento social na pandemia de COVID-19.

Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 25(1), 2411-2421. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020256.1.10792020

Bezerra, C. B., Saintrain, M. V. L., Braga, D. R. A., Santos, F. S., Lima, A. O. P.,

Brito, E. H. S., & Pontes, C. B. (2020). Impacto psicossocial do isolamento durante pandemia de covid-19 na população brasileira: análise transversal preliminar. Saúde e Sociedade, 29(4), Article

e200412. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104- 12902020200412

Campiolo, E. L, Kubo, H. K. L., Ochikubo, G. T., & Batista, G. (2020).

Impacto da pandemia do covid-19 no serviço de saúde: uma

revisão de literatura. InterAmerican Journal of Medicine and Health, 3, Article

e202003046. https://doi.org/10.31005/iajmh.v3i0.140

Canavêz,

F., Farias, C. P., & Luczinski, G. F. (2021). A pandemia de

covid-19 narrada por mulheres:

o que dizem as profissionais de saúde? Saúde Debate, 45(22), 112-123. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-11042021e109

Carvalho, A. F. M. C., Tiburi, G. B., Jucá, M. C. P., Sales,M., Neves, J. M. C., Da Silva, C. G. L., & Gadelha,

M. S. V. (2021).

Perdas, mortes e luto durante a pandemia de covid-19:

uma revisão sistemática. Brazilian

Journal of Development, 7(9),

90853-90870. https://doi.org/10.34117/bjdv7n9-307

Casselato, G., Mazorra, L., & Tinoco, V. (2020). Os desafios

enfrentados por idosos na pandemia - Algumas reflexões. Revista Kairós-Gerontologia, 23(28), 379-390.

Castro, J. L. C., Alves. M. E. S., &

Araújo, L. F. (2020). Representações sociais sobre a quarentena construídas por idosas brasileiras. Revista Kairós-Gerontologia,

23(28), 141-165.

Cepellos,

V. M. (2021). Feminização do envelhecimento: um fenômeno multifacetado muito além dos números. Pensata, 61(2), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-759020210208

Coutinho, M. P. L. (2017).

A técnica de Free Word Association Test sobre o prisma do software Tri-deux-

mots (version 5.2). Campo do Saber, 3(1), 219-243.

Da Silva, L. L. S., Lima, A. F. R., Polli, D. A., Razia, P. F. S., Pavão, L. F. A., Cavalcanti, M. A. F. H., & Toscano, C.

M. (2020). Medidas de distanciamento

social para o enfrentamento da COVID-19 no Brasil: caracterização e análise epidemiológica por estado. Caderno de Saúde Pública, 36(9),

Article e00185020. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00185020

Da Silva, F. C., Zamprogna, K. M., De Souza, S. S., Silva, D. H., & Sell, D. (2021).

Isolamento social e a

velocidade de casos de covid-19:

medida de prevenção da transmissão. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem, 42(esp), Article e20200238. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-1447.2021.20200238

De Castro, A. P. B., Moreira, M. F.,

Bermejo, P. H. S., Rodrigues, W.,

& Prata, D. N. (2020). Mortality and Years of Potential Life Lost Due to COVID-19 in Brazil. International Journal

of Environmental Research

and Public Health, 18(14), Article 7626. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147626

De Lima, K. C., Nunes, V. M. A., Rocha, N. S. P. D., Rocha,

P. M., De Andrade, I., Uchoa, S. A. C., & Cortez, L. R. (2020).

A pessoa idosa domiciliada sob distanciamento social: possibilidades

de enfrentamento à covid-19. Revista Brasileira de Geriatria e Gerontologia, 23(2),

Article e200092. https://doi.org/10.1590/1981- 22562020023.200092

De Lima, C. R. M., Sánchez-Tarragó, N., Moraes, D., Grings, L., & Maia, M. R. (2020). Emergência de saúde

pública global por pandemia de Covid-19: Desinformação, assimetria de informações e validação discursiva. Folha de Rosto, 6(2), 5-21. https://doi.org/10.46902/2020n2p5-21

De Melo, L. D., Arreguy-Sena, C., Gomes, A. M. T., Parreira,

P. M. D., Pinto, P. F., & Da Rocha,

J. C. C. C. (2020).

Representações sociais

elaboradas por pessoas idosas sobre ser idoso ou envelhecido: abordagens estrutural e processual. Revista de Enfermagem da UFSM, 10, Article

e53. https://doi.org/10.5902/2179769238464

De Sousa, I. T. C., Pestana,

A. M., Pavanello, L., Franz- Montan, M., & Cogo-Müller,

K. (2021). Máscaras

caseiras na pandemia de COVID-19: recomendações, características

físicas, desinfecção e eficácia de uso. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde, 30(4),

Article e2020997. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-49742021000400003

De Sousa, K. N., & De Souza, P. C. (2021). Social

Representation: A Theoretical Review of the Approach. Research,

Society and Development, 10(6),

Article e38610615881. https://doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v10i6.15881

Do Bú, E. A., De Alexandre, M. E. S., Bezerra, V. A. S., Sá-Serafim, R. C. N., & Coutinho,

M. P. L. (2020). Representations and social anchorages of the new coronavirus and the COVID-19 treatment by Brazilians. Estudos de Psicología, 37. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0275202037e200073

Eiguren, A., Idoiaga, N., Berasategi, N., & Picaza, M. (2021). Exploring

the Social and Emotional Representations Used by the Elderly

to Deal with the COVID-19

Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 586560. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586560

Erbesler, Z. A., & Demir, G. (2022). Determination of Death Anxiety

and Death-Related Depression Levels in the Elderly

During the COVID-19 Pandemic. OMEGA – Journal of Death and Dying. Advanced

Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228221082429

Faria, L., & Patiño, R. A. (2022). Dimensão psicossocial da pandemia

do Sars-CoV-2 nas práticas

de cuidado em saúde de idosos. Interface, 26, Article

e210673. https://doi.org/10.1590/interface.210673

Filho, Z. A., Nemer, C. R. B., Teixeira, E., Das Neves, A. L. M., Nascimento, M. H. M., Medeiros,

H. P., Panarra, B. A. C. S., Lima, P. A. V., Gigante, V. C. G., & De Oliveira,

V. L. G. (2021). Fatores associados

ao enfrentamento da pandemia da

COVID-19 por pessoas idosas

com comorbidades. Escola Anna Nery, 25(spe), Article e20200495. https://doi.org/10.1590/2177-9465-EAN- 2020-0495

Flament, C. (2001). Estrutura e dinâmica

das representações sociais.

In D. Jodelet (Ed.), As representações sociais (pp. 173-186). UERJ.

França, E. B., Ishitani, L. H., Teixeira, R. A., Abreu, D. M. X., Corrêa, P. R. L., Marinho, F., & Vasconcelos,

A. M.

N. (2020). Óbitos por COVID-19 no Brasil: Quantos e quais estamos identificando? Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia,

23, Article e200053. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-549720200053

Friesen, E., Michael, T., Schäfer, S. K., & Sopp, M. R. (2022). COVID-19-Related Distress is Associated with Analogue PTSD Symptoms after Exposure

to an Analogue Stressor. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2), Article

2127185. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2022.2127185

Fundação

Oswaldo Cruz. (2020). A gestão de riscos e governança na pandemia por covid-19 no Brasil: análise dos decretos estaduais no primeiro mês. https://www.arca.fiocruz.br/bitstream/icict/41452/2/relatorio_cepedes_gestao_riscos_covid19_final.pdf

Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. (2021a,

April 4 to 17). Observatório covid-19: semanas epidemiológicas [boletín 14 e 15]. https://portal.fiocruz.br/sites/portal.fiocruz.br/files/documentos/boletim_covid_2021-semanas_14-15-red.pdf

Fundação

Oswaldo Cruz. (2021b, November 21 to 27). Observatório covid-19: semana epidemiológica [boletín 47]. https://portal.fiocruz.br/documento/boletim-do-observatorio-covid-19-semana-47

Giamattey, M. E. P., Frutuoso, J. T., Bellaguarda, M. L. R., & Luna, I. J. (2022). Rituais Fúnebres na Pandemia de COVID-19

e Luto: Possíveis Reverberações. Escola Anna

Nery, 26(spe), Article e20210208. https://doi.org/10.1590/2177-9465-EAN-2021-0208

Islam, M. S., Sarkar, T., Khan S. H., Mostofa

Kamal, A. H., Hasan,

S. M. M., Kabir, A., Yeasmin, D., Islam, M. A., Amin Chowdhury, K. I., Anwar, K. S., Chughtai, A. A., & Seale, H. (2020). COVID-19 Related

Infodemic and its Impact on Public Health: A Global

Social Media Analysis. The American

Journal of Tropical

Medicine and Hygiene, 103(4), 1621-1629. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0812

Joia, L. A., Michelotto, F., & Lorenzo,

M. (2022). Sustainability and the Social

Representation of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Missing Link. Sustainability, 14(17), 10527. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710527

Jodelet, D. (2018). Ciências sociais e representações: estudo dos fenômenos representativos e processos sociais, do local ao global. Revista Sociedade e Estado, 33(2), 423-442.

https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-699220183302007

Kabad, J., & Souto, E. P. (2022).

Vacinação contra covid- 19 como direito e proteção social para a população idosa no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Geriatria e Gerontologia,

25(1), Article e210250. https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-22562022025.210250

Khalaf, O. O., Abdalgeleel, S. A., & Mostafa, N. (2022). Fear of COVID-19

Infection and its Relation to Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms Among Elderly

Population: Online Survey.

Middle East Current Psychiatry, 29(7), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-022-00177-1

Lima-Costa, M. F., Macinko, J., & Mambrini, J. V. M. (2022) Hesitação

vacinal contra a COVID-19 em

amostra nacional de idosos brasileiros: iniciativa ELSI-COVID,

março de 2021. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde, 31(1),

Article e2021469. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-49742022000100020

Lin, C. Y. (2020).

Social Reaction Toward the 2019

Novel Coronavirus

(covid-19). Social Health and Behavior, 3(1), 1-2. https://doi.org/10.4103/SHB.SHB_11_20

Mascarello, K. C., Vieira, A. C. B. C., De Souza,

A. S. S.,

Marcarini, W. D., Barauna, V. G., & Maciel, E. L. N. (2021). Hospitalização e morte

por COVID-19 e sua relação com determinantes sociais

da saúde

e morbidades no Espírito

Santo: um estudo

transversal. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde, 30(3), Article e2020919.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-49742021000300004

Moscovici, S. (2007). Representações sociais: investigações em psicologia social

(5nd ed.). Vozes.

Mota, S. N., Nogueira, J. M., Fernandes, B. K. C., Silva, H. G., Ferreira, M. A., &

Freitas, M. C. (2018). Enfoque estructural de las representaciones sociales de los adolescentes sobre el envejecimiento y las

personas mayores.

Cultura de los Cuidados,

22(50), 118-126. https://doi.org/10.14198/cuid.2018.50.11

Neves, D. A. B., De Brito, R. C., Códula, A. C. C., Silva, J. T., & Tavares, D. W.

(2014). Protocolo verbal e teste de associação livre de palavras: perspectivas de instrumentos de pesquisa introspectiva e projetiva na ciência da informação. PontodeAcesso, 8(3),

64-79. https://periodicos.ufba.br/index.php/revistaici/article/view/12917

Nogueira, K., & Di Grillo, M.

(2020). Theory of Social Representations:

History, Processes and Approaches. Research,

Society and Development, 9(9), Article

e146996756. https://doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v9i9.6756

Novais,

F., Cordeiro, C., Pestana, P. C., Côrte-Real,

B., Sousa, T. R., Matos, A. D., & Telles-Correia, D. (2021).

O impacto da COVID-19 na população idosa em Portugal: resultados

do Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement (SHARE). Acta Médica Portuguesa, 34(11), 761-766. https://doi.org/10.20344/amp.16209

Okai,

A. (2022, March 24). Women are Hit Hardest in

Disasters, so why are Responses Too Often Gender- Blind? United

Nations Development Programme Blog. https://www.undp.org/blog/women-are-hit-hardest-disasters-so-why-are-responses-too-often-gender-blind

Oliveira, A. S., Lopes, A. O. S., Santana,

E. S., Gobira, N. C. M. S., Miguens,

L. C. P., Reis, Luana A., & Reis, Luciana A. (2020). Representações

sociais de idosos sobre a COVID-19:

análise das imagens

publicadas

no discurso midiático. Revista Kairós-Gerontologia, 23(28), 461-477.

Organização Pan-Americana da

Saúde. (2009). Proteção da saúde mental em situações de epidemias. https:// www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2009/Protecao-da-Saude-Mental-em-Situaciones-de-Epidemias– Portugues.pdf

Oran,

D. P., & Topol, E. J. (2020). Prevalence of Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A

narrative review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 173(5), 362-367.

https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-3012

Pagno, M. (2021). Plano Nacional

de Operacionalização. Entenda a ordem de vacinação contra a

Covid-19 entre os

grupos prioritários. Ministério da Saúde da Brasil. https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/2021/janeiro/entenda-a-ordem-de-vacinacao-contra-a-covid-19-entre-os-grupos-prioritarios

Parreira, P., Mónico, L.,

Oliveira, D., Cavaleiro Rodrigues, J., & Graveto, J. (2018). Abordagem estrutural das representações sociais. In P. Parreira,

J. H. Sampaio, L. Mónico, T. Paiva & L. Alves (Coords.),

Análise das representações sociais e do impacto da aquisição de competências em empreendedorismo nos estudantes do Ensino Superior

Politécnico

(pp. 55-68). Guarda.

Passos, A. L., & Araújo, L. F. (2021). Representações sociais

sobre a

covid-19 entre professores de IES privadas

no Brasil. Summa Psicológica UST, 18(1), 40-46.

Pauli, B., Strupp, J., Schloesser, K., Voltz, R., Jung, N., Leise, C., Bausewein, C., Pralong, A., Simon, S. T., & Pallpan Consortium. (2022). It’s Like Standing in Front of a Prison Fence – Dying During the SARS-CoV2

Pandemic: A Qualitative

Study of Bereaved Relatives’ experiences. Palliative

Medicine, 36(4), 708-716.

https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163221076355

Pedreira, R. B. S., Dos Santos, L., Vilela, A. B. A., Rocha, R. M., & Boery, R. N. S. O. (2022).

Impactos reais e/ou potenciais da pandemia de COVID-19

na saúde mental de idosos. Arquivos de Ciências da Saúde da UNIPAR, 26(3), 441-457.

https://doi.org/10.25110/arqsaude.v26i3.2022.8488

Pereira, M. F. I., Rocha, L. C., Sartori,

L. F., De Souza, M. V.,

De Lima, R. A. S. M., & Rodrigues Júnior, A. L. (2022). Descriptive

Study of COVID-19

Mortality According to Sex,

Schooling, Age, Health Region and Historical

Series: State of Rio de Janeiro, January 2020 to August

2021. SciELO Preprints. https://doi.org/10.1590/SciELOPreprints.3614

Polinia, A. C., & Santos, M. F. S. (2020). Desenvolvimento de competências na perspectiva de docentes de ensino superior:

estudo em representações sociais. Educação e Pesquisa, 46,

Article e217461. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-4634202046217461

Rafaloski,

A. R., Zeferino, M. T., Forgearini,

B. A. O., Fernandes, G. C. M., & Menegon, F. A. (2020). Saúde mental das pessoas

em situação de desastre natural sob

a ótica dos trabalhadores envolvidos. Saúde em Debate, 44(2), 230-241.

https://doi.org/10.1590/0103- 11042020E216

Ramadas, S., & Vijayakumar, S.

(2021). Disenfranchised Grief and Covid-19: How do we Make it Less Painful?

Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, 1(2), 136-137.

https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2020.128

Rodrigues, L. G., Campos, F. L., Alonso, L. S., Silva, R. S., Oliveira, B. C., Rhodes, G. A. C., Silva, D. M., Sampaio,

A.

A., & Ferreira, R. C. (2020). Recomendações para o enfrentamento da pandemia de COVID-19 em

Instituições de Longa Permanência

para Idosos: rapid

review. Cadernos Saúde Coletiva. https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-462X202230030343

Romero, D. E., Muzy, J., Damacena, G. N., Souza, N. A., De Almeida, W. S., Szwarcwald, C. L., Malta, D. C., Barros, M. B. A., De Souza Júnior,

P. R. B., Azevedo, L. O., Gracie,

R., De Pina, M. F., Lima, M. G., Machado, I. E., Gomes, C. S., Werneck, A. O., & Da

Silva, D. R. P. (2021).

Idosos no contexto da pandemia da COVID-19 no Brasil: efeitos nas condições

de saúde, renda e trabalho. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 37(3),

Article e00216620. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00216620

Rubio, I. M., Sánchez-Lopes, P., Ángel, N. G., & Ruiz, N. F.

O. (2022). Psychological Consequences of fear of COVID-19: Symptom Analysis of Triggered

Anxiety and Depression Disorders in

Adolescents and Young Adults. International Journal

of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), Article 14171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114171

Santana, M. S., Santos, R. S., Barreto, A. C. M., Moura, R.

J. O., & Borges, S. C. S. (2022). Vulnerabilidade feminina

a violência física no período da pandemia de Covid-

19. Revista de Enfermagem

UERJ, 30, Article e65076. https://doi.org/10.12957/reuerj.2022.65076

Sousa, N. F. S., Lima, M. G., Cesar, C. L. G., & Barros, M. B.

A. (2018). Envelhecimento ativo: prevalência e diferenças de gênero e idade em estudo de base populacional. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 34(11), Article

e00173317. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00173317

Souto,

E. P., & Kabad, J. (2020). Hesitação

vacinal e os desafios para enfrentamento da pandemia de

COVID- 19 em

idosos no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Geriatria e Gerontologia, 23(5),

Article e210032. https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-22562020023.210032

Verges, P. (1992). L’evocation

de l’argent: Une méthode pour

la définition du noyau central

de la représentation [The Evocation of Money: A Method for Defining the Central Core of a Representation]. Bulletin de Psychologie, 45(405), 203-209.

Tavares, D. M. S., Oliveira, N. G. N., Marchiori, G. F., Guimarães, M. S. F., & Santana,

L. P. M. (2020). Idosos que moram sozinhos: conhecimento e medidas preventivas frente ao novo coronavirus. Revista Latino-Americana

de Enfermagem, 28, Article e3383. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.4675.3383

Tomé, A. M., & Formiga, N. S. (2020). Abordagens teóricas

e o uso da análise

de conteúdo como instrumento metodológico em representações sociais. Psicologia e Saúde em Debate, 6(2), 97-117.

https://doi.org/10.22289/2446-922X.V6N2A7

Wachelke,

J., & Wolter, R. (2011). Critérios de construção e relato da análise prototípica para as representações sociais. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 27(4), 521-526.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-37722011000400017

Wachelke, J., Wolter, R., & Matos, F. R. (2016).

Efeito do tamanho da amostra na análise

de evocações para representações sociais. Liberabit, 22(2), 153-160.

https://doi.org/10.24265/liberabit.2016.v22n2.03

Wegner, L., Mendoza-Vsconez, A. S.,

Mackey, S., McGuire, V.,

To, C., White, B., King, A. C., & Stefanick, M. L. (2021). Physical Activity,

Well-Being, and Priorities of Older Women During the COVID-19

Pandemic: A Survey of Women’s Health Initiative Strong and Healthy (WHISH) Intervention Participants. Translational

Behavioral Medicine, 11(12), 2155-2163. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibab122

World Health

Organization. (2020, January 23). Statement on the first meeting of the International Health Regulations

(2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak

of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) [Statement]. https://www.who.int/news/item/23-01-2020-statement-on-the-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)

Worldometer.

(n.d.). COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Retrieved

December 14, 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

Yildiz, B., Korfage, I. J., Witkamp, E. F. E., Goossensen, A., Lent, L. G. G., Pasman, H. R., Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D.,

Zee, M., & Heide, A. (2022). Dying in Times of COVID-19: Experiences in Different Care Settings – An Online

Questionnaire Study Among Bereaved Relatives (the CO-LIVE Study). Palliative Medicine, 36(4), 751- 761. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163221079698

Recibido:

04 de agosto de 2022

Aceptado:

30 de noviembre de 2022

Este es un artículo Open Access publicado bajo la licencia Creative

Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional. (CC-BY 4.0)