https://doi.org/10.24265/liberabit.2024.v30n2.886

ARTICULO DE INVESTIGACIÒN

Understanding Supports and Barriers in Women’s Careers:

A Literature Review

Entendiendo los

apoyos y las barreras de la carrera de mujeres: una revisión de literatura

Luana de Souza Barrosa,*,

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6376-4655

Deniel Gomes

Frutuosoa,

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7776-8024

Victor

Gabriel dos Santos Tomazb,

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8359-8500

Sônia Maria Guedes Gondimc,

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3482-166X

Ligia Carolina Oliveira-Silvaa,d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7487-9420

a Institute of Psychology, Federal University of Uberlândia, Brazil.

b Riberão Preto School of Philosophy, Sciences and Literature, University of São Paulo, Brazil.

c Postgraduate Program in Psychology, Federal University of Bahia, Brazil.

d Global

Institute for Women’s Leadership, Australian National University, Australia.

Para citar este artículo:

Barros, L. B., Frutuoso, D. G., Tomaz, V. G. S., Gondim, S. M. G., & Oliveira-Silva, L. C. (2024). Understanding Supports and Barriers in Women’s Careers: A Literature Review. Liberabit, 30(2), e886. https://doi.org/10.24265/liberabit.2024.v30n2.886

Abstract

Background: The persistent issue of gender discrimination in the workplace is a significant concern. Women continue to face many barriers and support systems are crucial for women’s professional development. Therefore, knowing about supports and barreiras more broadly can positively impact women. Objective: The objective of this article was to identify the barriers and supports that impact the professional development of women. Method: An integrative review of the literature was used with searches in two databases, Web of Science and Scopus, considering the period from 2013 to 2022 and selected 34 studies. Results: The results indicate that the studies address more barriers than supports. Barriers are most associated with gender discrimination, work-family conflict, distorted self-perceptions, lack of organizational support, negative professional experience, and social and cultural norms. Supports relate to the help of significant others, organizational support strategies, professional experience and skills, and individual strategies. Conclusion: The review provides contributions to support effective interventions and public policies that support gender equality, as well as helping organizations review human resources practices to better support women’s careers.

Keywords: Women; Career; Supports; Barriers.

Resumen

Antecedentes: la persistente cuestión de la discriminación de género en los sitios de trabajo es una preocupación significativa. Las mujeres siguen enfrentando numerosas barreras y los sistemas de apoyo son cruciales para el desarrollo profesional de las mujeres. Por lo tanto, conocer sobre los apoyos y barreras de forma más amplia puede impactar positivamente las mujeres. Objetivo: el objetivo de este artículo fue identificar las barreras y apoyos que impactan el desarrollo profesional de las mujeres. Método: fue utilizada una revisión integradora de la literatura que seleccionó 34 estudios. Se utilizó una revisión integrativa de la literatura con búsquedas en dos bases de datos, Web of Science y Scopus, considerando el período de 2013 a 2022 y se seleccionaron 34 estudios. Resultados: los resultados indican que los estudios abordan más barreras que apoyos. Las barreras están más asociadas con la discriminación de género, los conflictos entre el trabajo y la familia, las autopercepciones distorsionadas, la falta de apoyo organizacional, la experiencia profesional negativa y las normas sociales y culturales. Los apoyos se relacionan a la ayuda de otras personas significativas, las estrategias de apoyo organizacional, la experiencia y habilidades profesionales y las estrategias individuales. Conclusión: la revisión proporciona contribuciones para apoyar intervenciones y políticas públicas que favorezcan la igualdad de género, además de ayudar a las organizaciones a revisar las prácticas de recursos humanos para dar más apoyo a las carreras de las mujeres.

Palabras clave: mujeres; carrera; apoyo; barreras.

Introduction

Women who manage to enter the world of work note the marked presence of gender discrimination. There is a consensus that unequal treatment, lack of access to opportunities and resources, and the difficulty of upward mobility in organizations affect women and favor different career paths between genders (Lin, 2021). It is recognized that intersectionality, while simultaneous interaction of different social markers (gender, sexuality, race, nationality, and others) that make up the individual, can contribute to multiple discrimination and intensify segregations and injustices of certain groups, as is the case of women in organizational environments (Esposito, 2023). Canadian workers reported having been discriminated against in the workplace on the basis of gender (27.3%), race (16.1%) and disability (7%) (Hing et al., 2023). In Brazil, black women have a higher unemployment rate, close to 13.9% (Departamento Intersindical de Estatística e Estudos Socioeconômicos, 2022). These datas exemplify how being in marginalized groups impacts insertion and staying at work.

In a paper published in 2017 in the Journal of Applied Psychology, Wang and Wanberg (2017) revised the scholarship of individual careers in the last 100 years. Conclusions were that has increased by the 1980s. Therefore, for at least four decades, career psychology studies attempted to address the ways to minimize the prejudice that women face. However, data from the Global Gender Gap Report evidence the persistence, for instance, of a primal barrier: the gender pay gap. In the 21st century, women still tend to receive approximately 40% less than men due to obstacles to achieving senior positions or performing highly paid activities (World Economic Forum, 2020).

A fair amount of literature evidence

how gender exclusion phenomena are

present in organizations. One of

them is the «old boys club,» which explains the informal

contact network between

men that provides

privileged information and support and enhances career progress. This

deepens

gender

inequality in workplaces, narrowing

women’s recruitment and promotion (Liu & McDonald, 2022). Even though

constitutional mechanisms are attempting to break discrimination, such

initiatives are insufficient to promote gender equality in the short term.

In this

challenging environment, fraught with reiterated barriers to women’s career

growth, support from other people, the organization, and personal internal

resources becomes essential to facing the obstacles and achieving the

development of women’s careers. Receiving directions, constructive criticism,

financial support, and assistance with childcare are fundamental to broadening

professional opportunities (Ali et al., 2019; Yasmin & Husna,

2020).

Research

has pointed out that the different support formats generate benefits, such as

increased level of job satisfaction (Sigursteinsdottir

& Karlsdottir, 2022), work engagement (Bonaiuto et al., 2022), well-being (Du et al., 2023), sleep

quality (Seo & Mattos, 2024) and mental health (Acoba, 2024), reinforcing that it is an excellent promoter

of a good behavioral, physical and psychological functioning in individuals.

Although

the literature is rich considering the gender barriers women face, studies

focusing on both the barriers and supports are scarce, suggesting the necessity

of analyzing these variables together. There is also a need for research to

clarify which factors play these roles in the lives of multiple women with

different social markers, hierarchical positions, and professions. Therefore,

analyzing the evidence on barriers and support for women’s career advancement

can contribute to ensuring significant career opportunities (Lent et al.,

2001).

An

integrative review addressed that issue, as this type of review aims to

synthesize and critically analyze the knowledge gathered about a particular

topic (Soares et al., 2014; Toronto, 2020). This integrative review was

oriented by the following research question: What are the main barriers and

supports for women’s career development?

Besides broadening the comprehension scope of the supports and obstacles that influence women’s careers, we expect to provide evidence to evaluate people management policies and guide the development of strategies to foster gender equality and justice in workplaces.

Method

Search strategy

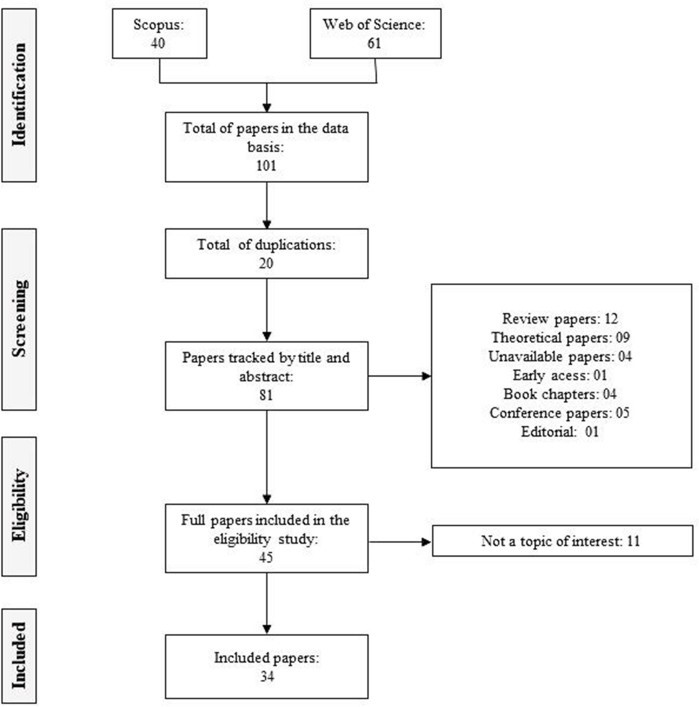

The review followed the PRISMA method (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). Initial research to select the empirical studies showed that databases such as Scielo (publishes scientific articles developed mainly in Latin American and Caribbean countries) and Lilacs (publishes scientific articles in Health Sciences developed primarily in Latin American and Caribbean countries) did not find any related content. We chose to use two more general databases, Web of Science and Scopus, which allow access to extensive international literature and gather publications in psychology.

The keywords selected for the research were carefully chosen to ensure the focus on our topic: («women») AND («career») AND («inequality») AND («barrier») AND («support»). As inclusion criteria, we considered only empirical studies from the last ten years (2013 to 2022), aiming to investigate the most recent literature about barriers and supports for women’s career development. We excluded theoretical studies, theses, and dissertations. The searches were conducted between 10/17/2022 and 12/13/2022.

Corpus analysis selection

Three of the research

authors who acted as independent judges carried out the process

of identifying and selecting

relevant articles. The results were

exported to a Microsoft Office Excel

spreadsheet to characterize authors, year, title, objective, publication journal, methodology (research design, sample, country

where data collection, instruments), and results.

Review or theoretical studies and inaccessible papers

were removed, which resulted in 101 papers. Of these, 20 were excluded

for duplicating, and 36 were removed

after reviewing the title and abstract due to

not addressing the inclusion

criteria and eligibility. The 45 remaining papers were integrally read, and 11 were excluded for not mentioning any barrier or support or for not approaching women’s careers.

Altogether, 34 papers

were considered for the final sample. Figure 1 illustrates the selection process for the studies included.

Data extraction

The judges participating in the

article selection stage also worked

independently to extract relevant data

from the articles in the analysis corpus. The

following information was extracted from the articles: (1) women’s career

barriers and supports,(2) research

analysis level, (3) research objectives,(4) main results,

and (5) sample characteristics. Another

judge was called to decide in case of disagreement among them.

Findings

We used thematic coding and categorization (Gibbs, 2009) to identify categories within the selected studies that could answer the research question. Therefore, this section is structured into two parts:

(1) Overview of the reviewed studies; and (2) Results of the content analysis regarding barriers and supports for women’s careers.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram

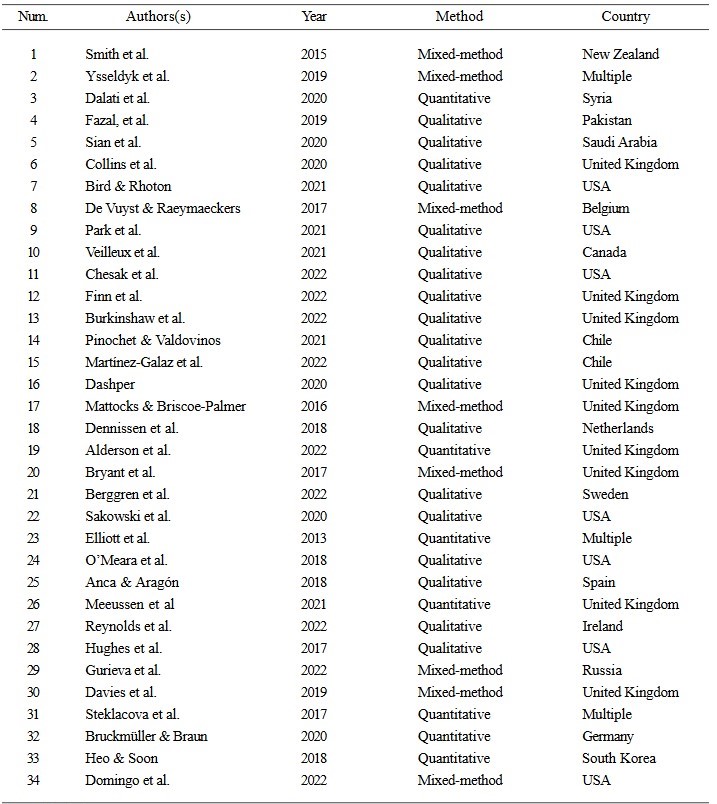

Overview of the reviewed studies

The results show recent publications addressing support and barriers in women’s careers. In total, 31 papers were published between 2017 and 2022, while no paper was published between 2014 and 2015. Regarding methodological approaches, 20 studies used qualitative approaches, focusing on semi- structured interviews, 06 used quantitative methods, and 08 used multimethods.

Studies were published in journals from different fields:

a) Education (n =

7); b) Gender issues (n = 7);c)

Health (n = 6); d) Psychology (n = 5); e) Business/ Management (n = 4); f) Multidisciplinary (n

= 2). Journals from economy,

science, and political science

had one publication each. Regarding

where the research was accomplished, the educational

setting was the primary

context in which studies were carried out, 15 dedicated to higher education.

The business context was approached

in 13 papers, followed by the health context, with four studies, and the cultural sector, with two studies.

As to intersectionality, only some studies considered it throughout the analysis. The social marker race/ethnicity was the most approached, with six studies, while culture/origin was addressed in three studies. Only one paper mentioned people with disabilities, and no paper analyzed sexual orientation or identity discrimination. Both men and women participated in several studies, and most of them made no distinctions regarding gender. Therefore, it is impossible to precisely identify the number of male and female participants, although there were only female participants in eight studies. The participants ranged from 18 to 69, gathering different professional experiences and career stages.

The participants’ nationalities included countries from Oceania (New Zealand), Asia (Pakistan), and South America (Chile). Two studies considered individuals from various countries. This diverse representation of the research participants underscores the inclusivity of the research. Nevertheless, the sample concentration is in the Northern Hemisphere, with most participants residing in The United States of America and the United Kingdom (n = 16). Nearly every study was written in English, with only one study published in Spanish.

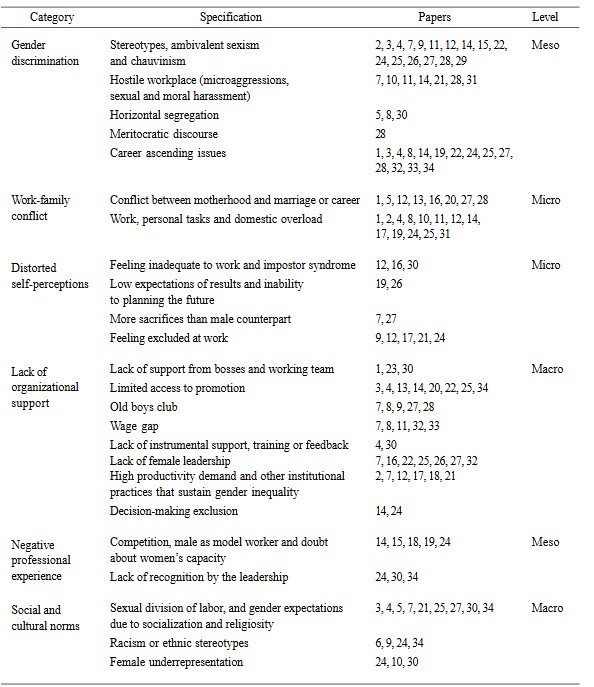

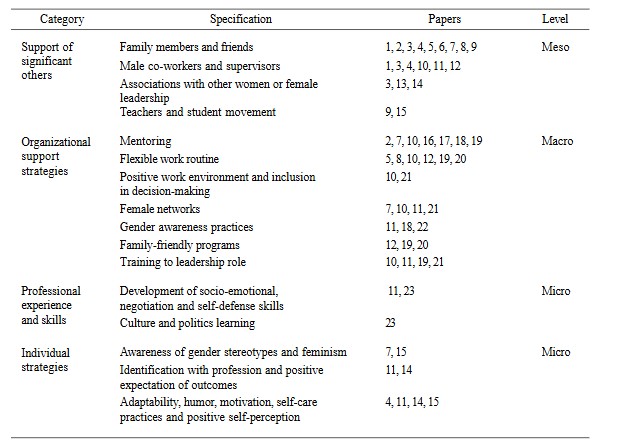

Most studies (n = 25) approached barriers and support, while nine discussed only the barriers, and no paper focused only on support variables. This means that approximately 26% of the included articles do not address aspects that contribute to promoting women’s career development. This suggests that literature is more prone to diagnosing what hampers career advancements than focusing on the possibilities and opportunities to overcome such barriers. Table 1 summarises the papers included in the review. After reading all of them, we categorize three levels of analysis for barriers and support variables: micro, meso, and macro. The micro level refers to the individual self- expression and particular life settings (biography, personality, skills, values). The meso level concerns relationships between individuals, work teams, and groups that generate positive or negative exchanges. Finally, the macro level emphasizes understanding society and the organization in an interconnected process. This comprehensive approach to the analysis ensures a thorough understanding of the topic. Tables 2 and 3 detail the identified barriers and support variables and levels.

Career Barriers

The results show that the barriers to women’s career development are multifaceted. Gender discrimination is primarily linked to societal expectations regarding how men and women should behave, resulting in discriminatory consequences (n = 26). The literature recurrently depicts those exclusion phenomena, encompassing challenges women face in advancing to leadership positions, experiencing harassment, and having lower visibility in the workplace.

The second barrier, work-family conflict, vividly illustrates the real-life implications of motherhood and the lack of family support on women’s career choices, stability, and transitions (n = 19). The third barrier, distorted self-perceptions, includes women’s perceptions of a lack of skills and training for professional activities, a lack of possible positive results prospection, and low self-esteem and self- concept (n = 14). The «impostor phenomenon,» for example, represents women’s difficulty in recognizing their professional merits, even when highly qualified.

The fourth barrier, the lack of organizational support, is deeply ingrained in organizational practices, severely limiting women’s opportunities (n = 27). Aspects such as the absence of support from colleagues and superiors, the dearth of training, and the persistent wage gaps between men and women exemplify this systemic issue. The concept of the «old boys club», for instance, starkly illustrates this barrier as it perpetuates the cycle of men in higher hierarchical positions favoring other men through personal recommendations, training, and mentoring, often at the expense of equally or more qualified women.

The fifth barrier, the negative professional experience, refers to the gendered treatment women receive, usually marked by discrimination, expectations of negative performance, and unappreciation of women’s potential and effectiveness (n = 8).

Finally, the sixth barrier category is related to social and cultural norms and refers to the macro-level of organization and society (n = 13). It includes the socialization of social roles of genders, racism, and the lack of public policies to equalize women’s career experience.

Career Supports

Career support was considered here as the interactions or relationships that provide women with encouragement or protection and generate feelings of attachment to a person, group, or organization. These include affection, loyalty, empathy, supportive listening, information, and guidance, stimulating women to face barriers and take advantage of career opportunities.

Considering the studies that address some support, 14 highlight the support of significant others, evidencing the role of family members and friends and reference people from the same workplace, for example, colleagues, supervisors, female leaders, or teachers. Participation and interaction with role models in places like student organizations are also shown as support factors. These different sources of support provide sharing/exchange of positive and negative experiences, besides counseling, encouragement, and improvement of women’s capacity to deal with adversities throughout their careers.

Organizational support strategies, for instance, refers to practices and strategies adopted in the workplace or student environment and includes mentoring, training, flexible working hours, female networking, and behavioral awareness. These practices and strategies work as support not only in helping women’s professional development but also for the management of barriers from the organizational perspective.

Two other supports appeared on a more minor frequency. The first was professional experience and skills, added to five studies, and self-conscientiousness and gender stereotype awareness, also mentioned in five studies. Professional maturity and abilities regard diversity and richness of repertoire that promotes professional development, such as research, services, teaching, accumulated professional experience, and socio-emotional skills. Individual strategies regard the importance of women acknowledging their minority condition in many workplaces, in which stereotypes and gender roles are strongly socially rooted. Practices that broaden engagement with feminism, the identification of gender stereotypes, and support for self-care, motivation, positive self-perception, and expectation of good results account for the process of self-knowledge.

Included papers in the literature

review

Table 2

Career Barriers Categories

Note: Paper’s numbers

can be found in Table 1. Source. Revised papers.

Table 3

Career Supports Categories

Discussion

This review aimed to answer the following question: What are the main barriers and supports for women’s career development? After analyzing the papers published between 2013 and 2022, we identified the main supports and barriers to women’s careers available in literature.

First, gender discrimination, which can be translated into microaggression, sexual or moral harassment, and sexism, affects women’s career progression negatively. For example, even when recognized by getting a job promotion, women are targets of several implicit and explicit discriminations, derived by male colleagues taking away female merit by concluding that their achievements are not due to their performance but rather to external factors (O’Meara et al., 2018). This and other behaviors reinforce gender exclusion in different ways: horizontal (the said «male» and «female» careers) and vertical (limits on the hierarchical ascension to women). The consequence is a poor distribution of genders in the workforce (e.g., Dashper, 2020; De Vuyst & Raeymaeckers, 2017; Fazal et al., 2019; Sian et al., 2020).

These discriminations are linked to cultural and social practices that define collective beliefs about where and how to be a woman in the labor market (Oliveira-Silva & Lopes, 2021). The gender prescriptions, reinforced daily, precede women’s insertion in the market and impact women’s career experiences in the future. For example, Wolniak et al. (2023) revealed that, even before entering university, women have fewer career aspirations than men, which means a lack of willingness to leadership. Continuing education and career self-realization may result from gender discrimination internalized by these women. Thus, it is possible to understand how gender cultural norms, sometimes internalized, shape the imagination of what men and women should be or have in the workplace.

Other studies point out the relevance of sociocultural dynamics in the recurrence of barriers in women’s careers. The social rules of what is expected of each gender (e.g., Anca & Aragón, 2018), the marginalization due to skin color or ethnicity (e.g., Domingo et al., 2022), and conflict between religious values and work requirements (e.g., Sian et al., 2020) were some of the addressed intersectional aspects. However, Domingo et al. (2022) indicate that social inequalities are at the individual level, as when compared to white women in the academic context, black women are more required to perform institutional tasks like committee and council meetings. Although the justification is to provide a voice to gender and ethnic minorities, this increases the workload, besides taking away time dedicated to research, which is the leading vehicle of career advancement in academia.

Like these other issues, the work-family conflict is inserted in these gender-social norms outcomes. The sexual division of labor-rooted beliefs reinforce sexism in the workplace by relying on women’s «natural aptitude» to care for and do housework, determining their career as the secondary option (Camarano & Pinheiro, 2023; Fernandez, 2019). By addressing these two roles, women are forced to equilibrate the demands of work and family, which often generates an overcharge, and sometimes, women have to leave their jobs (e.g., De Vuyst & Raeymaeckers, 2017; Mattocks & Briscoe-Palmer, 2016; Reynolds et al., 2022). Similarly, being a mother has countless consequences, as the motherhood bias hinders mothers from getting promoted or hired by people assuming that mothers are less reliable (Bao et al., 2021; Correll et al., 2007), especially by not corresponding to the ideal worker stereotype, which is highly flexible and available (Dashper, 2020). Some women report difficulty proving their «value» after returning from maternity. They also report feeling pressured, frequently experiencing guilt for distancing from child-rearing when trying to conciliate with career development.

Another barrier hindering women’s career development is the organization’s absence of supporting women. A recent Brazilian research study concluded a significant difference between men’s and women’s wages in that country’s judiciary. Even with wages fixed by laws, implicit inequalities exist in institutional structures that ignore the legal landmark in favor of men (Severi & Filho, 2022). This research exemplifies one of the scenarios that women still face a lack of institutional support. Thus, besides the wage gap (e.g., Heo & Soon, 2017), several barriers increase the inequality in organizations like lack of training (e.g., Veilleux et al., 2021), absence of team support (e.g., Davies et al., 2019), and lack of female leadership references (e.g., Dashper, 2020).

On the other hand, several individual barriers influence women’s career development. It means that, sometimes, women perceive themselves as less capable of performing tasks successfully, less important than others, or feel excluded in the workplace. Thereby, self-perception approaches the exclusion perception (e.g., Berggren et al., 2022), demerit of personal achievements (e.g., Finn et al., 2022), and low self-concept (e.g., Gurieva et al., 2022). The need for more studies that concern women’s self-perception is a gap that needs significant attention from researchers. Self-esteem and self-efficiency were also pointed out by Greer and Kirk (2022) as important supporting factors in women’s career transition.

Finally, negative professional experience involves repressing and silencing female voices (e.g., O’Meara et al., 2018) and female networks imitating male models (e.g., Dennissen et al., 2018). For example, women adopting male models can be explained by the queen-bee phenomenon, which refers to women in high hierarchical positions that aim to hamper their subordinates’ professional development instead of supporting them (Grangeiro et al., 2021). Thus, it is necessary to connect the reported negative professional experiences with what the literature on exclusion phenomena already recognizes, especially about interventions that help minimize or reduce these inequalities.

Regarding support, overall, the literature points to a set of strategies and interventions that boost women’s careers, assisting in their performance, making it easier to overcome career barriers, and providing career development. For example, the existence of support networks enables the sharing of experiences. It offers references that positively contribute to women’s capacity to face difficulties in their career development (e.g., Finn et al., 2022). The literature investigated also indicates that network support can empower racial or gender minorities, facilitating access to information, contact, and positive career opportunities (Park et al., 2021).

Organizational support strategies, which involve a broad range of formal practices to minimize gender inequalities in the workplace, also contribute to tackling career barriers for women when they aim to develop professional knowledge and skills. However, studies considered a few initiatives that can be more effective in changing the excluding organizational contexts. In the study of Veilleux et al. (2021) with neurosurgeons, for instance, the possibility of being oriented by a woman and developing professional connections with other women facilitated scientific publications. It positively influenced research proficiency, accounting for career enrichment. Professional contact with other women who have similar career paths suggests contributing to academic identification (Ysseldyk et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the identification with other women’s career paths represents a protective factor for mental health and contributes to confronting adversities in their careers. On the other hand, training opportunities are also suggested to help increase women’s representativeness in predominantly male fields (Veilleux et al., 2021). In summary, institutional or organizational support is one of the powerful tools for enhancing women’s careers, both to help women face hardships or achieve goals and to act as a protective factor for mental health.

Finally, professional experience and skills (Elliott et al., 2013; Fazal et al., 2019; O’Meara et al., 2018; Veilleux et al., 2021) and individual strategies (Bird & Rhoton, 2021; Fazal et al., 2019; Martínez-Galaz et al., 2022; Pinochet & Valdovinos, 2021) appear as supports to women’s careers, having the perks of allowing a relative control by women as individuals. The accumulated professional experience regarding improving skills and practices of teaching and learning for non-work related outcomes, such as sensitivity, resilience, and tolerance (Elliott et al., 2013), were also significant to the professional development of women leaders (O’Meara et al., 2018; Veilleux et al., 2021).

Individual strategies appear as supports related to the recognition of the implications of being a woman, contributing to their critical understanding of gendered socialization and norms so they can act against them (Martínez-Galaz et al., 2022; Pinochet & Valdovinos, 2021). In this review, evidence was found that the knowledge of gender role expectations could affect women’s careers, boosting the ability to overcome barriers and minimize working risks (Pinochet & Valdovinos, 2021). Besides recognizing and comprehending these factors as a critical step in reducing internal barriers, it is necessary to intervene in structures and contexts excluding women. Hence, changes are more efficient and lasting.

The reviewed studies did not analyze appropriately the barriers and supports considering social markers such as race, social class, sexual orientation, and gender identity. The studies that made it were restricted to the description of the life experience of that category, resulting in a superficial analysis of inequalities (Carvalho, 2020). This is alarming, as such barriers and supports can present other nuances depending on the intersectionalities. Therefore, we address the need for articulation and deepening social structures and power relations.

The barriers indicated by the revised studies contemplate not only individual or micro-level variables but also the role of society and the workplace. These macro and meso levels concern social interactions and institutional contexts and stress the need for structural changes. The lack of institutional support, gender exclusion practices, and the conflicts between work and family require actions of meso and macro levels mainly in order to cease the reproduction of gender differences in varied aspects of life in society. This is urgent, considering that socialization processes that perpetrate norms of gender differentiation remain, adding to the racist practices that create uneven performance requirements and reinforce discriminatory working conditions.

One critical aspect that requires change is the focus on barriers rather than on supports that could foster public policies and interventions to promote women’s careers. Knowledge of barriers and supports is essential, as the evidence shows that institutional support, the presence of female models, and individual aspects are critical to women’s career progress. The positive side is that such supports potentialize women’s competence in confronting the barriers, finding alternatives to their professional ascension, and managing their mental health.

Final Considerations and Limitations

This review aimed to map the empirical evidence on barriers and supports women’s career development. The results pointed out more barriers than supports. We identified four types of support and six types of career barriers. In sum, the support and their impacts are generally not explored. It discloses the necessity to invest in studies to open an avenue to explore new possibilities to reduce barriers and offer more support to women. Society, particularly work organizations, should be committed to repairing the social injustice women across the infinite decades have been subjected to.

As a limitation, despite the efforts, due to the wide range of articles that resulted from the initial research and the methodological decisions made, some studies that would be relevant to this review may still need to be addressed. The limitations of this review also include studies that discussed career supports and barriers of both genders and did not distinguish them quantitatively in the description of the sample. Despite this, it was decided to include them in the review to widely detect them in the female career, inferring that a considerable percentage of people of the gender of interest in these samples was included.

While the majority of the reviewed studies originate from the Global North, it is essential to recognize that the experiences of women in other regions, such as Latin America, may differ significantly. This underscores the urgent need for future studies to expand on data from countries outside this geopolitical axis, ensuring a more comprehensive understanding of women’s career development globally.

Organizations play a pivotal role in promoting gender equality. They need to critically review their supporting policies for women’s career development, as these policies can inadvertently impose barriers rather than offer opportunities for women to demonstrate their full potential. By structuring practices that recognize women’s importance and merit, organizations can change gender-discriminatory ideas about working performance.

Finally, we also expect that people management sectors invest more in gender bias awareness and mitigation of micro-aggressions, harassment, and sexism in the workplace. Although individual targeted solutions can be important resources to help women face adversities in their career path, proposing interventions focused on self-concept, self-efficacy, motherhood, relocation, and strengthening women’s networks is just one step in the process. Broader social changes are needed to hinder gender socialization processes that perpetuate gender inequality and injustice. The dissemination of knowledge about gender disparities through workshops, photo exhibitions and daily news on social networks are configured as an alternative to increase social awareness about the impact of this issue on careers. Government initiatives are also essential to ensure rights, access to opportunities, evaluation and improvement of existing public policies and implementation of new ones so that it is possible to approach gender equity more closely.

Acknowledgments

This work received financial support from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development - CNPq [identifier number 164714/ 2022-7], as well as from Research Foundation of the State of Minas Gerais [identifier number 11432].

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflits of interest with respect to authorship or publication of this article.

Ethical Responsibilities

No ethical approval was necessary to the conduction of this article.

Authorship contributions

LSB: conception and design of the research, search and selection of the articles, interpretation of data, discussion, and final revision of the manuscript.

DGF: search and selection of the articles, interpretation of data, discussion, and revision of the manuscript.

VGST: search and selection of the articles, interpretation of data, discussion, and revision of the manuscript.

SMGG: conception and design of the research, theorical framework, manuscript improvement and final revision.

LCOS: theoretical framework, design of the research, manuscript improvement and final revision.

References

Acoba, E. F. (2024). Social Support and Mental Health: The Mediating Role of Perceived Stress. Frontiers in Psychology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1330720

Alderson, D., Clarke, L., Schillereff, D., & Shuttleworth, E. (2022). Navigating the Academic Ladder as an Early Career Researcher in Earth and Environmental Sciences. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 48(2), 475- 486.http://doi.org/10.1002/esp.5497

Ali, M., Zin, M., & Hassan, Z. (2019). The Impact of Social Support and Corporate Culture on Women Career Advancement. Pakistan Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 7(3), 303-312.

Anca, C., & Aragón, S. (2018). Spanish Women’s Career Inhibitors: 2007-2017. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 31(1), 73-90. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARLA-04-2017-0118

Bao, X., Ke, P., Wang, J., & Peng, L. (2021). Material Penalty or Psychological Penalty? The Motherhood Penalty in Academic Libraries in China. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102452

Berggren, A., Almlöv, C., D’Urso, A., & Grubbström, A. (2022). «Screwedfrom the Start»: How Women Perceive Opportunities and Barriers for Building a Successful Research Career. Original Research, 7. http://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.809661

Bird, S. R., & Rhoton, L. A. (2021). Seeing Isn’t Always Believing: Gender, Academic STEM, and Women Scientists’ Perceptions of Career Opportunities. Gender & Society, 35(3), 422-448. http://doi.org/10.1177/08912432211008814

Bonaiuto, F., Fantinelli, S., Milani, A., Cortini, M., Vitiello, M. C., & Bonaiuto, M. (2022). Perceived Organizational Support and Work Engagement: The Role of Psychosocial Variables. Journal of Workplace Learning, 4(5), 418-436. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-11-2021-0140

Bruckmüller, S., & Braun, M. (2020). One Group’s Advantage or Another Group’s Disadvantage? How Comparative Framing Shapes Explanations of, and Reactions to, Workplace Gender Inequality. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 39(4), 457-475. http://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X20932631

Bryant, L. D., Burkinshaw, P., House, A. O., West, R. M., & Ward, V. (2017). Good Practice or Positive Action? Using Q Methodology to Identify Competing Views on Improving Gender Equality in Academic Medicine. BMJ Open, 7(8). http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015973

Burkinshaw, P., Bryant, L. D., Magee, C., Thompson, P., Cotterill, L. A., Mulvey, M. R., & Hewison, J. (2022). Ten Years of NIHR Research Training: Perceptions of the Programmes: A Qualitative Interview Study. BMJ Open, 12(1). http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046410

Camarano, A. A., & Pinheiro, L. (2023). Cuidar, verbo transitivo: caminhos para a provisão de cuidados no Brasil. Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada. http://dx.doi.org/10.38116/9786556350578

Carvalho, M. P. (2020). Interseccionalidade: Um exercício teórico a partir de uma pesquisa empírica. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 50(176), 360-374. http://doi.org/10.1590/198053147068

Chesak, S. S., Salinas, M., Abraham, H., Harris, C. E., Carey, E. C., Khalsa, T., Mauck, K. F., Feely, M., Licatino, L., Moeschler, S., & Bhagra, A. (2022). Experiences of Gender Inequity Among Women Physicians Across Career Stages: Findings from Participant Focus Groups. Women’s Health Reports, 3(1), 359-368. http://doi.org/10.1089/whr.2021.0051

Collins, H. C., Harrison, P. A., Palasinski, M., & (Pseudonym), M. (2020). Out of the Shadows: A Young Woman’s Journey from Hiding to Celebrating her Identity. The Qualitative Report, 25(12), 4310-4325. http://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4730

Correll, S. J., Bernard, S., & Paik, I. (2007). Getting a Job: Is There a Motherhood Penalty? American Journal of Sociology, 112(5), 1297-1338. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/511799

Dalati, S., Raudeliuniene, J., & Davidavicienë, V. (2020). Innovations in the Management of Higher Education: Situation Analysis of Syrian Female Students Empowerment. Marketing and Management of Innovations, 4, 245-254. http://doi.org/10.21272/mmi.2020.4-20

Dashper, K. (2020). Mentoring for Gender Equality: Supporting Female Leaders in the Hospitality Industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102397

Davies, J., Yarrow, E., & Syed, J. (2019). The Curious Under-Representation of Women Impact Case Leaders: Can we Dis Engender Inequality Regimes? Gender, Work & Organization, 27(2), 129-148. http://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12409

De Vuyst, S., & Raeymaeckers, K. (2017). Gender as a Multi-Layered Issue in Journalism: A Multi-Method Approach to Studying Barriers Sustaining Gender Inequality in Belgian Newsrooms. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 26(1), 23-38. http://doi.org/10.1177/1350506817729856

Dennissen, M., Benschop, Y., & Van den Brink, M. (2018). Diversity Networks: Networking for Equality? British Journal of Management, 30(4), 966-980. http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12321

Departamento Intersindical de Estatística e Estudos Socioeconômicos. (2022, 18 de noviembre). A persistente desigualdade entre negros e não negros no mercado de trabalho [boletín n.° 20]. https://www.dieese.org.br/boletimespecial/2022/boletimPopulacaoNegra2022.htm

Domingo, C. R., Gerber, N. C., Harris, D., Mamo, L., Pasion, S. G., Rebanal, R. D., & Rosser, S. V. (2022). More Service or More Advancement: Institutional Barriers to Academic Success for Women and Women of Color Faculty at a Large Public Comprehensive Minority-Serving State University. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 15(3), 365-379. http://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000292

Du, X., Zhou, M., Mao, Q., Luo, Y., & Chen, X. (2023).Positive Aging: Social Support and Social Well-Being in Older Adults-the Serial Mediation Model of Social Comparison and Cognitive Reappraisal. Current Psychology, 42, 22429-22435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03219-3

Elliot, C., Leak, J., Rockwell, B., & Luthy, M. (2013). «What my Guidance Councillor Should Have Told Me»: The Importance of Universal Access and Exposure to Executive-Level Advice. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 11(3), 239-252.

Esposito, E. (2023). Discourse, Intersectionality, Critique: Theory, Methods, and Practice. Critical Discourse Studies, 21(5), 505-521. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2023.2230602

Fazal, S., Naz, S., Khan, M. I., & Pedder, D. (2019). Barriers and enablers of women’s academic careers in Pakistan. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 25(2), 217-238. http://doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2019.1607467

Fernandez, B. P. M. (2019). Teto de vidro, piso pegajoso e desigualdade de gênero no mercado de trabalho brasileiro à luz da economia feminista: Por que as iniquidades persistem? Cadernos de Campo: Revista de Ciências Sociais, 26, 79-103.

Finn, G. M., Crampton, P., Buchanan, J. A., Balogun, A. O.,Tiffin, P. A., Morgan, J. E.,Taylor, E., Soto, C., & Kehoe, A. (2022). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Research Activity and Working Experience of Clinical Academics, with a Focus on Gender and Ethnicity: A Qualitative Study in the UK. BMJ Open, 12(6). http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057655

Gibbs, G. (2009). Análise

de dados qualitativos. Artmed.

Grangeiro, R. R., Rodrigues, M. S., Silva, L. E. N., & Esnard, C. (2021). Scientific Metaphors and Female Representativeness in Leadership Positions: A Bibliometric Analysis. Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho, 21(1), 1307-1316. https://dx.doi.org/10.5935/rpot/2021.1.19839

Greer, T. W., & Kirk, A. F. (2022). Overcoming Barriers to Women’s Career Transitions: A Systematic Review of Social Support Types and Providers. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.777110

Gurieva, S. D., Kazantseva, T. V., Mararitsa, L. V., & Gundelakh, O. E. (2022). Social Perceptions of Gender Differences and the Subjective Significance of the Gender Inequality Issue. Psychology in Russia, 15(2), 65-82. http://doi.org/10.11621/pir.2022.0205

Heo, S., & Yoon, S. (2017). Evidence of a Glass Ceiling for Arts and Culture Professionals in Korea. Applied Economics Letters, 25(16), 1170-1174. http://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2017.1406648

Hing, L. S. S., Sakr, N., Sorenson, J. B., Stamarski, C. S., Caniera, k., & Colaco, C. (2023). Gender Inequities in the Workplace: A Holistic Review of Organizational Processes and Practices. Human Resource Management Review, 33(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2023.100968

Hughes, C. C., Schilt, K., Gorman, B. K., & Brater, J. L. (2017). Framing the Faculty Gender Gap: A View from STEM Doctoral Students. Gender, Work and Organization, 24(4), 398-416. http://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12174

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., Brenner, B., Chopra, S., Davis, T., Talleyrand, R., & Suthakaran, V. (2001). The Role of Contextual Supports and Barriers in the Choice of Math/ Science Educational Options: A Test of Social Cognitive Hypotheses. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48(4), 474-483. http://doi.org/10.1037/00220167.48.4.474

Lin, Y. (2021, 20 june). The Literature Review of Gender Discriminations in Schools, Families and Workplaces [conference session]. Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Mental Health and Humanities Education, Qingdao, China. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.210617.134

Liu, C., & McDonald, S. (2022). Old Boy Networks at Work in the United States. In S. Horak (ed.), Informal Networks in International Business (pp. 199-215). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Martínez-Galaz, C. P., Del Campo, V. I., & Palomera-Rojas,P. V. (2022). Women’s Voices in Engineering: Academic Experiences, Obstacles, and Supports of Career Tenure. Formación universitaria, 15(4), 59-68. http://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-50062022000400059

Mattocks, K., & Briscoe-Palmer,

S. (2016). Diversity, Inclusion, and Doctoral Study: Challenges Facing Minority PhD Students in the United Kingdom. European Political

Science, 15, 476-492. http://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-016-0071-x

Meeussen, L., Begeny, C. T., Peters, K., & Ryan, M.K. (2021). In Traditionally Male Dominated Field, Women are Less Willing to Make Sacrifices for Their Careers Because Discrimination and Lower Fit with People up the Ladder Make Sacrifices Less Worthwhile. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 52(8), 588-601. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12750

Oliveira-Silva, L. C., & Lopes, A. B. M. (2021). Mulheres e liderança: barreiras, estereótipos e estratégias frente a uma visão androcêntrica. In I. V. Barbosa, V. S. L. Barbosa, & M. R. M. Araújo (orgs.), Contrassensos Contemporâneos do Mundo do Trabalho: Coleção Sociologias Necessárias (pp. 181-200). Criação Editora.

O’Meara, K., Templeton, L., & Nyunt, G. (2018). Earning Professional Legitimacy: Challenges Faced by Women, Underrepresented Minority, and Non-Tenure-Track Faculty. Teachers College Record, 120(12), 1-38. http://doi.org/10.1177/016146811812001203

Park, J., Salazar, C., Parikh, R., Zheng, J., Liwanag, A., & Dunewood, L. (2021). Connections Matter: Accessing Information about Education and Careers in STEM. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, 27(6), 85-113. http://doi.org/10.1615/JWomenMinorScienEng.2021033856

Pinochet, C., & Valdovinos, M. (2021). The Monopoly of Technique: Gender Inequalities and Female Agency in Support Work in the Chilean Musical Field. Resonancias, 25(48) 87-108. http://doi.org/10.7764/res.2021.48.5

Reynolds, R., Rogers, D., Crawley, L., Richards, H. L., & Fortune, D. G. (2022). Glass Ceiling versus Sticky Floor,Sideways Sexism and Priming a manager to Think Male as Barriers to Equality in Clinical Psychology: An Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis Approach. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 53(3), 225-233. http://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000456

Sakowski, S. A., Feldman, E. L., Jagsi, R., & Singer, K. (2020). Energizing the Conversation: How to Identify and Overcome Gender Inequalities in Academic Medicine. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 40(4), 274-278. http://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000296

Seo, S., & Mattos, M. K. (2024). The Relationship between Social Support and Sleep Quality in Older Adults: A Review of the Evidence. Archives

of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2023.105179

Severi, F., & Filho, J. (2022). Is there a Gender Pay Gap in the Brazilian Judiciary? Revista de administração pública, 56(2), 208-225. http://doi.org/10.1590/0034-761220210163x

Sian, S., Agrizzi, D., Wright, T., & Alsalloom, A. (2020). Negotiating Constraints in International Audit Firms in Saudi Arabia: Exploring the Interaction of Gender, Politics and Religion. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 84. http://doi.org/https:10.1016/j.aos.2020.101103

Sigursteinsdottir, H., & Karlsdottir, F. B. (2022). Does Social Support Matter in the Workplace? Social Support, Job Satisfaction, Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084724

Smith, D., Spronken-Smith, R.; Stringer, R., & Wilson, C.

A. (2015). Gender, Academic Careers, and the Sabbatical: A New Zealand Case Study. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(3), 589-603. http://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1107880

Soares, C. B., Hoga, L. A. K., Peduzzi, M., Sangaleti, C., Yonekura, T., & Silva, D. R. A. D. (2014). Revista da Escola de Enfermagem - USP, 48(2), 335-345. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0080-6234201400002000020

Steklacova, A., Bradac, O., De Lacy, P., & Benes, V. (2017). E-WIN Project 2016: Evaluating the Current Gender Situation in Neurosurgery Across Europe Interactive, Multiple-Level Survey. World Neurosurg, 104, 48-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.04.094

Toronto, C. E. (2020). Overview of the Integrative Review. In C. E. Toronto, & R. Remington (eds.), A Step-By-Step Guide to Conducting an Integrative Review (pp. 1-10). Springer.

Veilleux, C., Samuel, N., Yan, H., Bass, V., Al-Shahrani, R., Mansur, A., Rutka, J. T., Zadeh, G., Hodaie, M., & Milot, G. (2021). Cross-Sectional Analysis of Women in Neurosurgery: A Canadian Perspective. Neurosurgical Focus, 50(3), 1-7. http://doi.org/10.3171/2020.12.FOCUS20959

Wang, M., & Wanberg, C. R. (2017). 100 Years of Applied Psychology Research on Individual Careers: From Career Management to Retirement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 546-563. http://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000143

World Economic Forum. (2020). Global Gender Gap Report 2020. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf

Yasmin, T., & Husna, C. A. (2020). Familial Support as a Determinant of Women Career Development: A Qualitative Study. Asian Journal of Social Sciences and Legal Studies, 2(4), 76-87. http://doi.org/10.34104/ajssls.020.076087

Ysseldyk, R., Greenaway, K. H., Hassinger, E., Zutrauen, S., Lintz, J., Bhatia, M. P., Frye, M., Starkenburg, E., & Tai, V. (2019). A Leak in the Academic Pipeline: Identity and Health Among Postdoctoral Women. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1297. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01297

Wolniak, G. C., Che Chen-Bendle, E. C., & Tackett, J. L. (2023).Exploring Gender Differences in LeadershipAspirations: A Four-Year Longitudinal Study of CollegeStudents from Adverse Backgrounds. AERA Open, 9. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/23328584231183665

Recibido: 11 de junio de 2024

Aceptado: 07 de noviembre de 2024

Este es un artículo Open Access publicado bajo la licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional. (CC-BY 4.0)